Contents

- Lesson Goals

- Preparation

- Installation and Setup

- Basics of Text Analysis and Working with Non-English and Multilingual Text

- Relevant Python Libraries

- Developing Python Code for Multilingual Text Analysis

- Conclusion

- Suggested Reading

Lesson Goals

Many of the resources available for learning computational methods of text analysis focus on English-language texts and corpora, and often lack the information which is needed to work with non-English source material. To help remedy this, this lesson will provide an introduction to analyzing non-English and multilingual text (that is, text written in more than one language) using Python. Using a multilingual text composed of Russian and French, this lesson will show how you can use computational methods to perform three fundamental preprocessing tasks: tokenization, part-of-speech tagging, and lemmatization. Then, it will teach you to automatically detect the languages present in a preprocessed text.

To perform the three fundamental preprocessing steps, this lesson uses three common Python packages for Natural Language Processing (NLP): the Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK), spaCy, and Stanza. We’ll start by going over these packages, reviewing and comparing their core features, so you can understand how they work and discern which tool is right for your specific use case and coding style.

Preparation

Prerequisites

This lesson is aimed at those who are unfamiliar with text analysis methods, particularly those who wish to apply such methods to multilingual corpora or texts not written in English. While prior knowledge of Python is not required, it will be helpful to understand the structure of the code. Having a basic knowledge of Python syntax and features is recommended – it would be useful, for example, for the reader to have familiarity with importing libraries, constructing functions and loops, and manipulating strings.

Code for this tutorial is written in Python 3.10 and uses the NLTK (v3.8.1), spaCy (v3.7.4), and Stanza (v1.8.2) libraries to perform its text processing. If you are entirely new to Python, this Programming Historian lesson will be helpful to read before completing this lesson.

Installation and Setup

You will need to install Python3 as well as the NLTK, spaCy, and Stanza libraries, which are all available through the Python Package Index (PyPI). For more information about installing libraries using PyPI, see their guide on installing packages.

Basics of Text Analysis and Working with Non-English and Multilingual Text

Computational text analysis is a broad term that encompasses a wide variety of approaches, methodologies, and Python libraries, all of which can be used to handle and analyze digital texts of all scales. Harnessing computational methods allows you to quickly complete tasks that are far more difficult to perform without these methods. For example, the part-of-speech tagging method described in this lesson can be used to quickly identify all verbs and their associated subjects and objects across a corpus of texts. This could then be used to develop analyses of agency and subjectivity in the corpus (as, for example, in Dennis Tenen’s article Distributed Agency in the Novel).

In addition to the methods we cover in this lesson, other commonly-performed tasks which are simplified by computation include sentiment analysis (which provides a quantitative assessment of the sentiment of a text, generally spanning a numerical scale indicating positivity or negativity) and Named Entity Recognition (NER) (which recognizes and classifies entities in a text into categories such as place names, person names, and so on).

For further reading on these methods, please see the Programming Historian lessons Sentiment Analysis for Exploratory Data Analysis and Sentiment Analysis with ‘syuzhet’ using R for sentiment analysis, and Finding Places in Text with the World Historical Gazetteer and Corpus Analysis with spaCy for Named Entity Recognition. The lesson Introduction to Stylometry with Python may be of interest to those looking to further explore additional applications of computational text analysis.

To prepare the text for computational analysis, we first need to perform certain ‘preprocessing’ tasks. These tasks can be especially important (and sometimes particularly challenging) when working with multilingual text.

For example, you might first need to turn your documents into machine-readable text, using methods such as Optical Character Recognition (OCR), which can extract text from scanned images. OCR can work very well for many documents, but may give far less accurate results on handwritten scripts, or documents that don’t have clearly delineated text (e.g. a document with low contrast between the text and the paper it is printed on). Depending on the languages and texts you work with (and the quality of the OCR method), you might therefore need to ‘clean’ your text - i.e. correct the errors made by OCR - in order to use it in your analysis. For an introduction to OCR and cleaning, see these Programming Historian lessons: OCR with Google Vision API and Tesseract and Cleaning OCR’d text with Regular Expressions.

Key Steps and Concepts of Text Analysis Relevant to the Lesson

Once you have a clean text that is machine-readable, you’ll still need to perform further preprocessing tasks in order to prepare the text for analysis. Yet again, however, these tasks can often involve particular challenges and considerations, depending on the types of languages and texts you are working with.

In this lesson, we focus on three key preprocessing tasks: tokenization, part-of-speech (POS) tagging, and lemmatization. We’ll show how these tasks can be applied to a multilingual and non-English language text.

Tokenization

Tokenization is the segmentation of a text into component parts, or ‘tokens’. These tokens can vary in size, but you will most commonly see texts tokenized into either words or sentences. An example sentence could be tokenized into a list of words like so: [And, now, for, something, completely, different] (this sentence is taken from Chapter 5 of the NLTK Book). For this lesson, we will focus on tokenizing text into such lists of words. In other contexts, such as when tokenizing a text for a Large Language Model (LLM), different tokenization methods should be applied (for example, it sometimes involves assigning each unique token (letters, punctuation) a unique integer value).

In this lesson, we will start by tokenizing our text. This will enable to us to then perform POS tagging and lemmatization on the textual data. Without prior tokenization, we would not be able to access the text as a series of words, to which we can apply our tagging and lemmatization.

Part-of-Speech (POS) Tagging

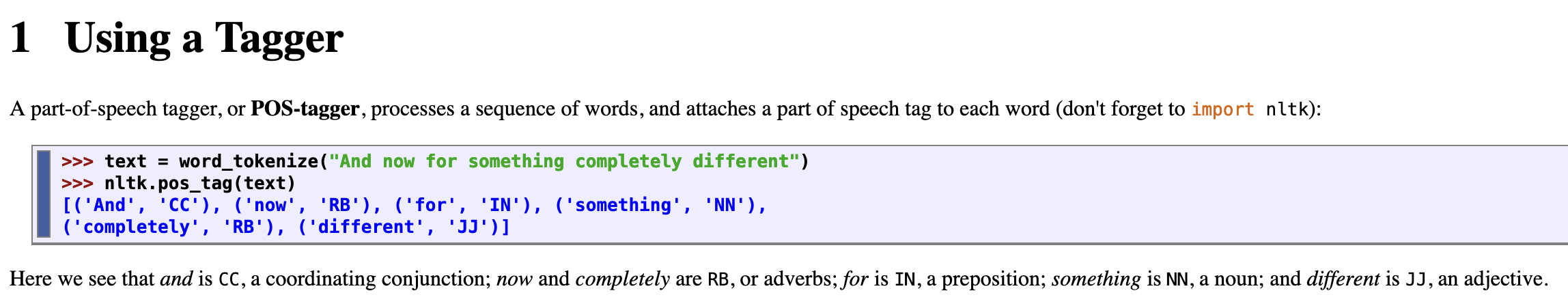

POS tagging involves marking each word in a text with its corresponding part-of-speech (e.g. ‘noun’, ‘verb’, ‘adjective’, etc.). POS taggers can use rule-based algorithms, following set definitions to infer the proper tag to attach to a word, or stochastic (probabilistic) approaches, in which the tagger calculates the probability of a given set of tags occurring, and assigns them to an untrained text. The sentence used as an example for tokenization above, for example, might look like the following with its parts of speech tagged by NLTK: [(‘And’, ‘CC’), (‘now’, ‘RB’), (‘for’, ‘IN’), (‘something’, ‘NN’), (‘completely’, ‘RB’), (‘different’, ‘JJ’)]. The sentence is split into its component words, and each word is put into a tuple with its corresponding POS tag.

Figure 1. Screenshot of part-of-speech tagging from the NLTK Book, Chapter 5.

Lemmatization

Lemmatization reduces a word to its dictionary form, which is known as a ‘lemma’. The lemmatized form of the word coding, for example, would be code, with the ‘-ing’ suffix removed.

Challenges with Non-English and Multilingual Text Analysis

Tokenization, POS tagging and lemmatization are presented in this lesson as practical examples of the differences between how NLTK, spaCy, and Stanza handle these fundamental processing tasks. Indeed, how text analysis packages implement certain tasks can vary depending on a number of criteria: the choice of algorithm, the choice of the models and the training data they rely on, etc. Therefore, how well the packages peform for any specific language depends on the quality and availability of these components. They may reproduce assumptions that align with features of the English language which do not always transfer well to features of other languages. For example, some default tokenizing procedures assume that words are series of characters separated by a space. This might work well for English and other alphabet-based languages such as French, but character-based languages, such as Mandarin, handle word boundaries very differently. Tokenizing a text in Chinese may therefore involve artificially inserting spaces between characters, a process known as ‘segmentation’ (see Melanie Walsh’s Text Pre-Processing for Chinese for an introduction). Similarly, when tokenizing a word into its component letters for languages written in Latin or Cyrillic alphabets, combining diacritical marks would pose unique issues, as the diacritical marks are represented by Unicode characters that are separate from the letter(s) they are applied to.

As it stands, many of the resources available for learning computational methods of text analysis privilege English-language texts and corpora. These resources often omit the information needed to begin working with non-English source material, and it might not always be clear how to use or adapt existing tools to different languages. However, high-quality models capable of processing a variety of languages are increasingly being introduced. For example, support for performing tasks such as POS tagging has been expanded for Russian and French, thanks to the introduction and refinement of new models by spaCy and Stanza. Still, many tutorials and tools you encounter will default to English-language compatibility in their approaches. It is also worth noting that the forms of English represented in these tools and tutorials tends to be limited to Standard English, and that other forms of the language are likewise underrepresented.

Working with multilingual texts presents even further challenges: for example, detecting which language is present at a given point in the text, or working with different text encodings. If methods often privilege English-language assumptions, they are also often conceived to work with monolingual texts and do not perform well with texts that contain many different languages. For example, as discussed later in this lesson, the commonly recommended sentence tokenizer for NLTK (PunktSentenceTokenizer) is trained to work with only one language at a time, and therefore won’t be the best option when working with multilingual text. This lesson will show how models can be applied to target specific languages within a text, to maximize accuracy and avoid improperly or inaccurately parsing text.

In this lesson, we compare NLTK, spaCy, and Stanza, because they each contain models that can navigate and parse the properties of many languages. However, you may still have to adjust your approach and workflow to suit the individual needs of the language(s) and texts you are analyzing. There are a number of things to consider when working with computational analysis of non-English text, many of them specific to the language(s) of your texts. Factors such as a text’s script, syntax, and the presence of suitable algorithms for performing a task, as well as relevant and sufficient examples in training data, can all affect the results of the computational methods applied. In your own work, it’s always best to think through how an approach might suit your personal research or project-based needs, and to investigate the assumptions underlying particular methods (by looking into the documentation of a particular package) before applying any given algorithm to your texts. Being flexible and open to changing your workflow as you go is also helpful.

Relevant Python Libraries

The Python libraries used in this lesson (NLTK, spaCy, and Stanza) were chosen due to their support for multilingual text analysis, their robust user communities, and their open source status. While all of the libraries are widely used and reliable, they each have different strengths and features: they cover different languages, they use different syntax and data structures, and each focuses on slightly different use cases. By going over their main features and comparing how to interact with them, you will be able to develop a basic familiarity with each package that can guide which one(s) you choose for your own projects.

The Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK)

NLTK is a suite of libraries for building Python programs that work with language data. Originally released in 2001, NLTK has excellent documentation and an active, engaged community of users, which makes it an excellent tool when beginning to work with text processing. More advanced users will also find its wide variety of libraries and corpora useful, and its structure makes it very easy to integrate into one’s own pipelines and workflows.

NLTK supports different numbers of languages for different tasks: it contains lists of stopwords for 23 languages, for example, but only has built-in support for word tokenization in 18 languages. ‘Stopwords’ are words which are filtered out of a text during processing, often because they are deemed unimportant for the task being performed (e.g. the word the may be removed to focus on other vocabulary in the text).

For further reading, the NLTK Book is an excellent reference, as is the official documentation linked above. Unfortunately, the book and documentation are only available in English.

spaCy

spaCy has built-in support for a greater variety of languages than NLTK, with pretrained models of differing levels of complexity available for download. Overall, spaCy focuses more on being a self-contained tool than NLTK. Rather than integrating NLTK with a separate visualization library such as matplotlib, for example, spaCy has its own visualization tools, such as displaCy, that can be used in conjunction with its analysis tools to visualize your results.

spaCy is known for its high speed and efficient processing, and is often faster than NLTK and Stanza. In addition, if you want to save time on processing speed, you can use a smaller, less accurate model to perform something like POS tagging on a simple text, for example, rather than a more complex model that may return more accurate results, but take longer to download and run.

Documentation for spaCy is only available in English, but the library supports pipelines for 25 different languages. Over 20 more languages are also supported, but do not yet have pipelines (meaning only select features, such as stopwords, may be supported for those languages). For more information on supported languages, please consult their documentation.

Stanza

Stanza was built with multilingual support in mind from the start, and working with text in different languages feels very intuitive and natural with the library’s syntax. Running a pipeline on a text allows you to access various aspects of a text – for example, parts of speech and lemmas – with minimal coding.

While often slower than NLTK and spaCy, Stanza has language models that are not accessible through the other libraries. The package contains pretrained neural models supporting 70 languages. A full list of its models can be viewed on StanfordNLP’s Github, and more information on its pipelines is available on a related page. Stanza’s pipelines are built with neural network components trained on multilingual corpora, meaning they have used machine learning algorithms trained on annotated text, rather than parameter-based approaches to NLP (e.g. comparing words in a text to a predefined dictionary). For example: if performing POS tagging on a text, the algorithms will generate their own tags based on predictions trained on a large corpus of pre-tagged text, taking in mind the context of each word (its position in relation to other words in the sentence). A paramater-based approach, on the other hand, would look up each term in a predefined dictionary and output its tag, ignoring the context of the word within the broader text.

Documentation for Stanza is only available in English. For more information, please consult this paper on Stanza.

To summarize, all three packages can be very effective tools for analyzing a text in a non-English language (or multiple languages), and it’s worth investigating each package’s syntax and capabilities to see which one best suits your individual needs for a given project.

Developing Python Code for Multilingual Text Analysis

During the coding portion of the lesson, you will take an excerpt of text from Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace (1869) in the original Russian, which contains a substantial amount of French text. We’ll show you how to split it into sentences, detect the language of each sentence, and perform some analysis methods on the text. The text file we will be using contains an excerpt from the first book of the novel, and was sourced from Wikipedia. This is the only textual resource you’ll need to go through the lesson, and it can be downloaded from the Programming Historian repository. If you would like to follow along in a Jupyter notebook, we’ve prepared one which includes all the code below, which you can access via your browser.

If you would like to work through the lesson without loading the text file, you can use the following text as a string instead:

war_and_peace = """

— Eh bien, mon prince. Gênes et Lucques ne sont plus que des apanages, des поместья, de la famille Buonaparte. Non, je vous préviens, que si vous ne me dites pas, que nous avons la guerre, si vous vous permettez encore de pallier toutes les infamies, toutes les atrocités de cet Antichrist (ma parole, j’y crois) — je ne vous connais plus, vous n’êtes plus mon ami, vous n’êtes plus мой верный раб, comme vous dites. Ну, здравствуйте, здравствуйте. Je vois que je vous fais peur, садитесь и рассказывайте.

Так говорила в июле 1805 года известная Анна Павловна Шерер, фрейлина и приближенная императрицы Марии Феодоровны, встречая важного и чиновного князя Василия, первого приехавшего на ее вечер. Анна Павловна кашляла несколько дней, у нее был грипп, как она говорила (грипп был тогда новое слово, употреблявшееся только редкими). В записочках, разосланных утром с красным лакеем, было написано без различия во всех:

«Si vous n’avez rien de mieux à faire, M. le comte (или mon prince), et si la perspective de passer la soirée chez une pauvre malade ne vous effraye pas trop, je serai charmée de vous voir chez moi entre 7 et 10 heures. Annette Scherer».

— Dieu, quelle virulente sortie! — отвечал, нисколько не смутясь такою встречей, вошедший князь, в придворном, шитом мундире, в чулках, башмаках, и звездах, с светлым выражением плоского лица.

Он говорил на том изысканном французском языке, на котором не только говорили, но и думали наши деды, и с теми тихими, покровительственными интонациями, которые свойственны состаревшемуcя в свете и при дворе значительному человеку. Он подошел к Анне Павловне, поцеловал ее руку, подставив ей свою надушенную и сияющую лысину, и покойно уселся на диване.

— Avant tout dites moi, comment vous allez, chère amie? Успокойте меня, — сказал он, не изменяя голоса и тоном, в котором из-за приличия и участия просвечивало равнодушие и даже насмешка.

"""

Loading and Preparing the Text

First, let’s load our text file so we can use it with our analysis packages. To start, you’ll open the file and assign it to the variable named war_and_peace, so we can reference it later on. Then, you’ll print the contents of the file to make sure it was read correctly. For the purposes of this tutorial, we are using a short excerpt from the novel.

with open("war_and_peace_excerpt.txt") as file:

war_and_peace = file.read()

print(war_and_peace)

Running this code should output the text as shown in Developing Python Code for Multilingual Text Analysis above.

Now, let’s remove the newline characters. Newline characters are used to signify the end of a line in character encoding specifications such as Unicode. We will replace all newlines (represented as a \n in the code) with a space, assign the cleaned text to a new variable named cleaned_war_and_peace and print it to check what we’ve done. Replacing the newline characters with a space will combine the text into a continuous string and homogenize the text. This ensures that the tokenizer is not mislead into creating sentence splits where there shouldn’t be any. This is the only modification to the text that we will be doing for the purposes of this lesson, but if you are interested in different steps you can take to prepare your text for multilingual analysis, please consult this article.

cleaned_war_and_peace = war_and_peace.replace("\n", " ")

print(cleaned_war_and_peace)

Your output from the code above will be a copy of the text without newline characters.

Now that we’ve read the file and prepared our text, let’s begin to process it. First, you’ll install and import the packages (NLTK, spaCy, and Stanza).

To install these packages, run these commands in your terminal:

pip install nltk

pip install spacy

pip install stanza

And then, to import the packages after installation, write these lines in your Python script:

import nltk

import spacy

import stanza

Tokenization

Now that the libraries are imported, let’s perform sentence tokenization on the text. Tokenization is simply splitting a text into smaller units, such as sentences or words, which allows you to break the text down to analyze it more effectively. If we are working with a sentence as a string, for example, our code will not naturally break it down into its component words or letters. Instead, we need to tokenize the sentence to work with each word as a separate piece of data. In this tutorial, we’ll begin by tokenizing using NLTK, before detecting each sentence’s language.

There are different sentence tokenizers included in the NLTK package. NLTK recommends using the PunktSentenceTokenizer for a language specified by the user (see here for more information), but if you are working with multilingual text this may not be the best approach. If you have a piece of text containing multiple languages, applying a single tokenization model trained to work with one language will produce less accurate results (if we selected French, for instance, the model’s methods for tokenizing French text would also be applied to the Russian in our text, for which it may be less effective). These language-specific models take into account cases particular to their respective languages – such as peculiarities in word or sentence boundaries common in those languages – rather than merely splitting by punctuation.

Tokenization with NLTK

For the purposes of this tutorial, we will use the sent_tokenize method built into NLTK without specifying a language, which will allow us to apply a basic tokenization algorithm that will work with both the Russian and French sentences in our example. For more advanced uses in which accuracy over a large body of text is important, it is preferable to apply the appropriate language models provided by a library. For examples of specifying a language with NLTK’s tokenizer, please consult this Stack Overflow comment, which outlines the languages available in NLTK.

First, let’s install the punkt resources required to use the tokenizer:

import nltk

nltk.download('punkt')

Then we import the sent_tokenize method and apply it to our war_and_peace variable:

from nltk.tokenize import sent_tokenize

nltk_sent_tokenized = sent_tokenize(cleaned_war_and_peace)

# if you were going to specify a language, the following syntax would be used: nltk_sent_tokenized = sent_tokenize(war_and_peace, language="russian")

The entire text is now accessible as a list of sentences within the variable nltk_sent_tokenized. We can easily figure out which sentences are in which languages, because we are working with a small selection of text as an example. When working with a larger amount of textual data, finding sentences may require more in-depth analysis of the text. The code example below will loop through all of the sentences in our list, printing each on a new line to allow for easy assessment:

# printing each sentence in our list

for sent in nltk_sent_tokenized:

print(sent)

Tokenizing the text into sentences allows us to work with it at sentence level, which enables us to analyze the excerpt at a finer level. Let’s print three sentences we’ll be working with: one entirely in Russian, one entirely in French, and one that is in both languages. The language of the sentences will become important as we apply different methods to them later in the lesson.

# printing the Russian sentence at index 5 in our list of sentences

rus_sent = nltk_sent_tokenized[5]

print('Russian: ' + rus_sent)

# printing the French sentence at index 2

fre_sent = nltk_sent_tokenized[13]

print('French: ' + fre_sent)

# printing the sentence in both French and Russian at index 4

multi_sent = nltk_sent_tokenized[4]

print('Multilang: ' + multi_sent)

Output:

Russian: Так говорила в июле 1805 года известная Анна Павловна Шерер, фрейлина и приближенная императрицы Марии Феодоровны, встречая важного и чиновного князя Василия, первого приехавшего на ее вечер.

French: — Avant tout dites moi, comment vous allez, chère amie?

Multilang: Je vois que je vous fais peur, садитесь и рассказывайте.

Tokenization with spaCy

Now, let’s perform the same sentence tokenization using spaCy, using the same sample three sentences. As you can see, the syntax with spaCy is quite different: the library has a built-in multilingual sentence tokenizer. To access the list of sentences tokenized by the spaCy model, you first need to apply the model to the text by calling the nlp method, then assign the doc.sents tokens to a list.

# downloading our multilingual sentence tokenizer

python -m spacy download xx_sent_ud_sm

# loading the multilingual sentence tokenizer we just downloaded

nlp = spacy.load("xx_sent_ud_sm")

# applying the spaCy model to our text variable

doc = nlp(cleaned_war_and_peace)

# assigning the tokenized sentences to a list so it's easier for us to manipulate them later

spacy_sentences = list(doc.sents)

# printing the sentences to our console

print(spacy_sentences)

Let’s assign our sentences to variables, like we did with NLTK. spaCy returns its sentences not as strings, but as ‘spaCy tokens’. In order to print them as we did with the NLTK sentences above, we’ll need to convert them to strings (for more information on built-in types in Python, such as strings and integers, please consult this documentation). This will allow us to concatenate them with a prefix identifying their language, as Python won’t let us concatenate a string and a non-string type. Given our small sample dataset, we can easily specify our sentences using their indices in our list. To examine the entire list of sentences, as we might for a larger dataset, we would choose a different method to look at the strings, such as iterating through each item in the list (we’ll do this with our Stanza tokens below).

# concatenating the Russian sentence and its language label

spacy_rus_sent = str(spacy_sentences[5])

print('Russian: ' + spacy_rus_sent)

# concatenating the French sentence and its language label

spacy_fre_sent = str(spacy_sentences[13])

print('French: ' + spacy_fre_sent)

# concatenating the French and Russian sentence and its label

spacy_multi_sent = str(spacy_sentences[4])

print('Multilang: ' + spacy_multi_sent)

Output:

Russian: Так говорила в июле 1805 года известная Анна Павловна Шерер, фрейлина и приближенная императрицы Марии Феодоровны, встречая важного и чиновного князя Василия, первого приехавшего на ее вечер.

French: — Avant tout dites moi, comment vous allez, chère amie?

Multilang: Je vois que je vous fais peur, садитесь и рассказывайте.

We can see that both models tokenized the sentences in the same way, as the NLTK and spaCy indices (5, 13, and 4) are matched to the same sentences from the text.

Tokenization with Stanza

Now, let’s perform the same operation with Stanza, using its built-in multilingual pipeline. Stanza uses pipelines to pre-load and chain up a series of processors, with each processor performing a specific NLP task (e.g., tokenization, dependency parsing, or Named Entity Recognition). For more information on Stanza’s pipelines, please consult this documentation.

from stanza.pipeline.multilingual import MultilingualPipeline

# setting up our tokenizer pipeline

nlp = MultilingualPipeline(processors='tokenize')

# applying the pipeline to our text

doc = nlp(cleaned_war_and_peace)

# printing all sentences to see how they tokenized

print([sentence.text for sentence in doc.sentences])

Now, let’s find the same three sentences which we used with NLTK and spaCy above. Like spaCy, Stanza converts its processed text to tokens that behave differently from strings.

First, let’s add the sentence tokens to a list, converting them to strings. This makes it easier for us to find specific sentences by their indices. Stanza tokenizes the sentences in the text differently, so we had to change our index for the French sentence from 13 to 12 to make sure our variables stayed the same.

# creating an empty list to append our sentences to

stanza_sentences = []

# iterating through the sentence tokens created by the tokenizer pipeline and appending to the list

for sentence in doc.sentences:

stanza_sentences.append(sentence.text)

# printing our sentence that is only in Russian

stanza_rus_sent = str(stanza_sentences[5])

print('Russian: ' + stanza_rus_sent)

# printing our sentence that is only in French

stanza_fre_sent = str(stanza_sentences[12])

print('French: ' + stanza_fre_sent)

# printing our sentence in both French and Russian

stanza_multi_sent = str(stanza_sentences[4])

print('Multilang: ' + stanza_multi_sent)

Output:

Russian: Так говорила в июле 1805 года известная Анна Павловна Шерер, фрейлина и приближенная императрицы Марии Феодоровны, встречая важного и чиновного князя Василия, первого приехавшего на ее вечер.

French: — Avant tout dites moi, comment vous allez, chère amie?

Multilang: Je vois que je vous fais peur, садитесь и рассказывайте.

Automatically Detecting Different Languages

Now that your three example sentences are ready, you can begin to analyse each one. First, let’s computationally detect each sentence’s language, starting with the monolingual examples.

NLTK includes a module called TextCat that supports language identification using the TextCat algorithm. For further information, please consult the documentation for the module here. This algorithm applies n-gram frequencies (n-grams are sequences of adjacent symbols, such as letters or syllables, in a particular order) to profile languages and the text we’re analyzing. It then compares the two using a distance measure to estimate the language of the text. It’s worth noting that TextCat does not allow us to print its probability estimate for a particular language estimate. Let’s try the module on our sentences below:

# downloading an NLTK corpus reader required by the TextCat module

nltk.download('crubadan')

# loading the TextCat package and applying it to each of our sentences

tcat = nltk.classify.textcat.TextCat()

rus_estimate = tcat.guess_language(rus_sent)

fre_estimate = tcat.guess_language(fre_sent)

multi_estimate = tcat.guess_language(multi_sent)

# printing the results

print('Russian estimate: ' + rus_estimate)

print('French estimate: ' + fre_estimate)

print('Multilingual estimate: ' + multi_estimate)

Output:

Russian estimate: rus

French estimate: fra

Multilingual estimate: rus

As we can see, TextCat correctly identified the Russian and French sentences. Since it can’t output more than one language per sentence, it assumed that our multilingual sentence is in Russian.

We’ll examine other ways to detect the languages in multilingual sentences after we’ve perform our sentence classification using spaCy and Stanza.

Let’s try spaCy first. First, we install the spacy_langdetect package from the Python Package Index:

pip install spacy_langdetect

Then we import it and use it to detect our languages:

from spacy.language import Language

from spacy_langdetect import LanguageDetector

# setting up our pipeline

Language.factory("language_detector")

nlp.add_pipe('language_detector', last=True)

# running the language detection on each sentence and printing the results

rus_doc = nlp(spacy_rus_sent)

print(rus_doc._.language)

fre_doc = nlp(spacy_fre_sent)

print(fre_doc._.language)

multi_doc = nlp(spacy_multi_sent)

print(multi_doc._.language)

Output:

{'language': 'ru', 'score': 0.9999978739911013}

{'language': 'fr', 'score': 0.999995246346788}

{'language': 'ru', 'score': 0.7142842829707301}

As expected, we got similar results with spaCy. Note that the confidence score (printed after the language guess) is far lower for the multilingual sentence.

Now let’s try Stanza, which has a built-in language identifier:

# importing our models required for language detection

from stanza.models.common.doc import Document

from stanza.pipeline.core import Pipeline

# setting up our pipeline

nlp = Pipeline(lang="multilingual", processors="langid")

# specifying which sentences to run the detection on, then running the detection code

docs = [stanza_rus_sent, stanza_fre_sent, stanza_multi_sent]

docs = [Document([], text=text) for text in docs]

nlp(docs)

# printing the text of each sentence alongside the language estimates

print("\n".join(f"{doc.text}\t{doc.lang}" for doc in docs))

Output:

Так говорила в июле 1805 года известная Анна Павловна Шерер, фрейлина и приближенная императрицы Марии Феодоровны, встречая важного и чиновного князя Василия, первого приехавшего на ее вечер. ru

— Avant tout dites moi, comment vous allez, chère amie? fr

Je vois que je vous fais peur, садитесь и рассказывайте. fr

We can see that Stanza classified the final sentence as French, deviating from the other models.

Classifying multiple languages within the same sentence is not a simple problem to solve, and requires more granular analysis than a sentence-by-sentence approach. One method would be to tokenize the sentence into its component words, then try to detect the language of each word. Then, we can group consecutive words of the same language into new strings, each consisting only of one language. For our particular case study here, we might try to split the string into its component languages by detecting and separating all non-Roman script into its own string. Below is an implementation of this method.

First, we tokenize the sentence into its component words, using the wordpunct_tokenize module. As earlier in the lesson, when we tokenized our text into sentences, performing our tokenization first allows us to perform additional operations later on.

from nltk.tokenize import wordpunct_tokenize

tokenized_sent = wordpunct_tokenize(multi_sent)

Next, we check whether each word contains Cyrillic characters, and split the word tokens into two strings: Cyrillic and non-Cyrillic script. For simplicity’s sake, we’ll omit any punctuation in this example. We use a regular expression (a sequence of characters that specifies a match pattern in text) to detect Cyrillic characters. (For more information on regular expressions, this Programming Historian lesson is a great resource.)

# importing the regex package so we can use a regular expression

import regex

# importing the string package to detect punctuation

from string import punctuation

# setting empty lists we will later populate with our words

cyrillic_words = []

latin_words = []

Next, we iterate through each word in our sentence using RegEx to detect Cyrillic characters. If Cyrillic is found, we append the word to our cyrillic_words list; otherwise, we append the word to the latin_words list. If a tokenized word consists only of punctuation, we continue without appending it. We can then print our lists to see what has been appended:

for word in tokenized_sent:

if word in punctuation:

continue

else:

if regex.search(r'\p{IsCyrillic}', word):

cyrillic_words.append(word)

else:

latin_words.append(word)

print(cyrillic_words)

print(latin_words)

Output:

['садитесь', 'и', 'рассказывайте']

['Je', 'vois', 'que', 'je', 'vous', 'fais', 'peur']

Finally, we can join our lists into strings, which allows us run the TextCat algorithm on them.

# joining the lists into a string, with each word separated by a space (' ')

cyrillic_only_list = ' '.join(cyrillic_words)

latin_only_list = ' '.join(latin_words)

# now we use TextCat again to detect their languages

tcat = nltk.classify.textcat.TextCat()

multi_estimate_1 = tcat.guess_language(cyrillic_only_list)

multi_estimate_2 = tcat.guess_language(latin_only_list)

# printing our estimates

print('Cyrillic estimate: ' + multi_estimate_1)

print('Latin estimate: ' + multi_estimate_2)

Output:

Cyrillic estimate: rus

Latin estimate: fra

Of course, this method may not work as well on a different text, because our text has the advantage of containing only one language in the Cyrillic alphabet. If it contained multiple languages written in Cyrillic, we would have to take a different approach. For example, we might try to identify certain Cyrillic characters that are unique to one of the languages, or at least more commonly used within it.

Part-of-Speech Tagging

Now, let’s perform part-of-speech tagging for our sentences using spaCy and Stanza.

NLTK does not support POS tagging on languages other than English out-of-the-box, but you can train your own model using a corpus to tag languages other than English. Documentation on the tagger, and how to train your own, can be found here.

Part-of-Speech Tagging with spaCy

Tagging our sentences with spaCy is very straightforward. Since we know we’re working with Russian and French, we can download the appropriate spaCy models and use them to get the proper POS tags for the words in our sentences. The syntax remains the same regardless of which language model we use. We’ll begin with Russian:

# downloading our Russian model from spaCy

python -m spacy download ru_core_news_sm

# loading the model

nlp = spacy.load("ru_core_news_sm")

# applying the model

doc = nlp(spacy_rus_sent)

# printing the text of each word and its POS tag

for token in doc:

print(token.text, token.pos_)

Output:

Так ADV

говорила VERB

в ADP

июле NOUN

1805 ADJ

года NOUN

известная ADJ

Анна PROPN

Павловна PROPN

Шерер PROPN

, PUNCT

фрейлина NOUN

и CCONJ

приближенная ADJ

императрицы NOUN

Марии PROPN

Феодоровны PROPN

, PUNCT

встречая VERB

важного ADJ

и CCONJ

чиновного ADJ

князя NOUN

Василия PROPN

, PUNCT

первого ADJ

приехавшего VERB

на ADP

ее DET

вечер NOUN

. PUNCT

Now, we can do the same for our French sentence:

# downloading our French model from spaCy

python -m spacy download fr_core_news_sm

# loading the corpus

nlp = spacy.load("fr_core_news_sm")

# applying the model

doc = nlp(spacy_fre_sent)

# printing the text of each word and its POS tag

for token in doc:

print(token.text, token.pos_)

Output:

— PUNCT

Avant ADP

tout ADV

dites VERB

moi PRON

, PUNCT

comment ADV

vous PRON

allez VERB

, PUNCT

chère ADJ

amie NOUN

? PUNCT

For multilingual text, we can use the words we generated earlier to tag each language separately, then join the words back into a complete sentence again.

Below, we split our sentence into Russian and French words as before, only this time we preserve the punctuation. We’ll do this by appending any punctuation to the list which has been most recently appended to: this will preserve the proper placement of each punctuation mark (it will append the punctuation to the word that precedes it). This will be useful to anyone who wishes to preserve the punctuation of the original text as part of their analysis. To do this, we need a new variable – last_appended_list – to use as a way to keep track of which list we last appended to. If a period followed the word bonjour, for example, our last_appended_list variable would show that the last list we appended to was latin_words. Thus, we could append the period to the latin_words list, where it would correctly follow the word preceding it.

# creating our blank lists to append to later

cyrillic_words_punct = []

latin_words_punct = []

# initializing a blank string to keep track of the last list we appended to

last_appended_list = ''

# iterating through our words and appending based on whether a Cyrillic character was detected

for word in tokenized_sent:

if regex.search(r'\p{IsCyrillic}', word):

cyrillic_words_punct.append(word)

# updating our string to track the list we appended a word to

last_appended_list = 'cyr'

else:

# handling punctuation by appending it to our most recently used list

if word in punctuation:

if last_appended_list == 'cyr':

cyrillic_words_punct.append(word)

elif last_appended_list == 'lat':

latin_words_punct.append(word)

else:

latin_words.append(word)

last_appended_list = 'lat'

print(cyrillic_words)

print(latin_words)

Output:

['садитесь', 'и', 'рассказывайте', '.']

['Je', 'vois', 'que', 'je', 'vous', 'fais', 'peur', ',']

We can then join these lists into strings, allowing us to run our language detection on them. We’ll use a regular expression to remove the extra space before each punctuation mark (this space was created when we tokenized the sentence into words). This will preserve the punctuation as it was present in the original sentence.

# joining the lists to strings

cyrillic_only_list = ' '.join(cyrillic_words)

latin_only_list = ' '.join(latin_words)

# using our regular expression to remove extra whitespace before the punctuation marks

cyr_no_extra_space = regex.sub(r'\s([?.!,"](?:\s|$))', r'\1', cyrillic_only_list)

lat_no_extra_space = regex.sub(r'\s([?.!,"](?:\s|$))', r'\1', latin_only_list)

# checking the results of the regular expression above

print(cyr_no_extra_space)

print(lat_no_extra_space)

Output:

садитесь и рассказывайте.

Je vois que je vous fais peur,

Finally, we can tag each list of words using the appropriate language model. We load the model, apply it to our Russian and French text, and print the results.

# loading and applying the model

nlp = spacy.load("ru_core_news_sm")

doc = nlp(cyr_no_extra_space)

# printing the text of each word and its POS tag

for token in doc:

print(token.text, token.pos_)

# and doing the same with our French sentence

nlp = spacy.load("fr_core_news_sm")

doc = nlp(lat_no_extra_space)

for token in doc:

print(token.text, token.pos_)

Output:

садитесь VERB

и CCONJ

рассказывайте VERB

. PUNCT

Je PRON

vois VERB

que SCONJ

je PRON

vous PRON

fais VERB

peur NOUN

, PUNCT

Part-of-Speech Tagging with Stanza

Now, let’s perform POS tagging using Stanza. We’ll start with Russian: loading our Russian pipeline, applying it to our sentence, and printing the POS tags detected by Stanza:

# loading our pipeline and applying it to our sentence, specifying our language as Russian ('ru')

nlp = stanza.Pipeline(lang='ru', processors='tokenize,pos')

doc = nlp(stanza_rus_sent)

# printing our words and POS tags

print(*[f'word: {word.text}\tupos: {word.upos}' for sent in doc.sentences for word in sent.words], sep='\n')

Output:

word: Так upos: ADV

word: говорила upos: VERB

word: в upos: ADP

word: июле upos: NOUN

word: 1805 upos: ADJ

word: года upos: NOUN

word: известная upos: ADJ

word: Анна upos: PROPN

word: Павловна upos: PROPN

word: Шерер upos: PROPN

word: , upos: PUNCT

word: фрейлина upos: NOUN

word: и upos: CCONJ

word: приближенная upos: VERB

word: императрицы upos: NOUN

word: Марии upos: PROPN

word: Феодоровны upos: PROPN

word: , upos: PUNCT

word: встречая upos: VERB

word: важного upos: ADJ

word: и upos: CCONJ

word: чиновного upos: ADJ

word: князя upos: NOUN

word: Василия upos: PROPN

word: , upos: PUNCT

word: первого upos: ADJ

word: приехавшего upos: VERB

word: на upos: ADP

word: ее upos: DET

word: вечер upos: NOUN

word: . upos: PUNCT

We will now do the same for our French sentence using the same syntax, with the French model:

# loading our pipeline and applying it to our sentence, specifying our language as French ('fr')

nlp = stanza.Pipeline(lang='fr', processors='tokenize,mwt,pos')

doc = nlp(stanza_fre_sent)

# printing our words and POS tags

print(*[f'word: {word.text}\tupos: {word.upos}' for sent in doc.sentences for word in sent.words], sep='\n')

Output:

word: — upos: PUNCT

word: Avant upos: ADP

word: tout upos: PRON

word: dites upos: VERB

word: moi upos: PRON

word: , upos: PUNCT

word: comment upos: ADV

word: vous upos: PRON

word: allez upos: VERB

word: , upos: PUNCT

word: chère upos: ADJ

word: amie upos: NOUN

word: ? upos: PUNCT

For the multilingual analysis, Stanza’s multilingual pipeline allows us to apply a more streamlined approach than spaCy, since it can return POS tags using similar syntax to the examples above. We import our multilingual pipeline, apply it to our text, and then print the results.

# imports so we can use Stanza's MultilingualPipeline

from stanza.models.common.doc import Document

from stanza.pipeline.core import Pipeline

from stanza.pipeline.multilingual import MultilingualPipeline

# running the multilingual pipeline on our French, Russian, and multilingual sentences simultaneously

nlp = MultilingualPipeline(processors='tokenize,pos')

docs = [stanza_rus_sent, stanza_fre_sent, stanza_multi_sent]

nlp(docs)

# printing the results

print(*[f'word: {word.text}\tupos: {word.upos}' for sent in doc.sentences for word in sent.words], sep='\n')

Output:

word: Так upos: ADV

word: говорила upos: VERB

word: в upos: ADP

word: июле upos: NOUN

word: 1805 upos: ADJ

word: года upos: NOUN

word: известная upos: ADJ

word: Анна upos: PROPN

word: Павловна upos: PROPN

word: Шерер upos: PROPN

word: , upos: PUNCT

word: фрейлина upos: NOUN

word: и upos: CCONJ

word: приближенная upos: VERB

word: императрицы upos: NOUN

word: Марии upos: PROPN

word: Феодоровны upos: PROPN

word: , upos: PUNCT

word: встречая upos: VERB

word: важного upos: ADJ

word: и upos: CCONJ

word: чиновного upos: ADJ

word: князя upos: NOUN

word: Василия upos: PROPN

word: , upos: PUNCT

word: первого upos: ADJ

word: приехавшего upos: VERB

word: на upos: ADP

word: ее upos: DET

word: вечер upos: NOUN

word: . upos: PUNCT

Lemmatization

Finally, let’s perform lemmatization on our sentences using spaCy and Stanza (NLTK does not provide out-of-the-box lemmatization for non-English languages). Lemmatization is the process of replacing all the inflected forms of a word (e.g., looks, looked) with a single item, the ‘lemma’, which is the word in its basic form (in this case, look). For example, the sentence I typed a letter would, if lemmatized, be changed to I type a letter. The word typed was reduced to the lemma type, removing the ‘-d’ suffix to simplify the word into a basic form.

Lemmatization with spaCy

To keep things short, we’ll use only the multilingual sentence as an example to demonstrate lemmatization with spaCy. However, spaCy does not have a single multilingual lemmatization corpus, so we’ll first need to split the multilingual sentence into its component parts again. Then, we can run separate models on the Russian and French parts. For more info on lemmatization using spaCy, including a list of supported languages, visit spaCy’s lemmatizer documentation.

First, we load our models, apply them to our text, and print the lemmas returned by spaCy. We’ll start with Russian:

# loading and applying the model

nlp = spacy.load("ru_core_news_sm")

doc = nlp(cyr_no_extra_space)

# printing the words and their lemmas

for token in doc:

print(token, token.lemma_)

Output:

садитесь садитесь

и и

рассказывайте рассказывать

. .

And then the French text:

# loading and applying the model

nlp = spacy.load("fr_core_news_sm")

doc = nlp(lat_no_extra_space)

# printing the words and their lemmas

for token in doc:

print(token, token.lemma_)

Output:

Je je

vois voir

que que

je je

vous vous

fais faire

peur peur

, ,

Lemmatization with Stanza

Finally, we’ll lemmatize the Russian, French, and multilingual sentences with Stanza. The syntax is very similar to the one we used for POS tagging with the multilingual pipeline earlier.

# imports so we can run the multilingual pipeline

from stanza.models.common.doc import Document

from stanza.pipeline.core import Pipeline

from stanza.pipeline.multilingual import MultilingualPipeline

# adding the 'lemma' processor to the pipeline and running it on our sentences

nlp = MultilingualPipeline(processors='tokenize,lemma')

docs = [stanza_rus_sent, stanza_fre_sent, stanza_multi_sent]

nlped_docs = nlp(docs)

# iterating through each sentence's words and printing the lemmas

for doc in nlped_docs:

lemmas = [word.lemma for t in doc.iter_tokens() for word in t.words]

print(lemmas)

Our output shows the lemmatized Russian, French, and multilingual sentences, printed as lists of words:

Output:

['так', 'говорить', 'в', 'июль', '1805', 'год', 'известный', 'Анна', 'Павловна', 'Шерер', ',', 'фрейлить', 'и', 'приближенный', 'императрица', 'Мария', 'феодоровнянный', ',', 'встречать', 'важный', 'и', 'чиновный', 'князь', 'Василий', ',', 'первый', 'приехать', 'на', 'она', 'вечер', '.']

['успокойте', 'я', ',', '—ат', 'сказать', 'он', ',', 'не', 'изменять', 'голос', 'и', 'тон', ',', 'в', 'который', 'из-за', 'приличие', 'и', 'участие', 'просвечивальский', 'равнодушие', 'и', 'даже', 'насмешка', '.']

['moi', 'voir', 'que', 'moi', 'vous', 'faire', 'peur', ',', 'садитесь', 'и', 'рассказывайте', '.']

As we can see, lemmatizing the sentences has replaced our words with their dictionary, non-inflected forms. The verb vois in the French sentence, for example, was replaced with its infinitive voir, and the Russian говорила was replaced with its infinitive говорить.

This process is helpful when you want to identify all instances of a particular word in a text: for example, if we were interested in examining themes of seeing and vision in the text, lemmatization would allow us to reliably identify every time the lemma voir occurs, without worrying about all its possible conjugated forms. For this same reason, lemmatization therefore also makes counting word frequencies much more accurate, especially for highly inflected languages.

Conclusion

You now have a basic knowledge of different packages which you can use for multilingual text analysis, which can hopefully guide your personal projects. You also have an understanding of how to approach non-English text using computational methods, and gained some strategies for working with multilingual text that will help you develop methodologies for your own project needs.

We covered how to tokenize text, automatically detect languages, identify parts of speech and lemmatize text in different languages. These preprocessing steps can prepare for further text analyses, such as sentiment analysis or topic modeling, or may already provide some results for analyses that will be beneficial for your work. Most importantly, you have a base of knowledge and some example code that opens up new opportunities for understanding and applying computational methods to multilingual and non-English text. This will broaden the range of scholarship which you can now interact with, and deepen your understanding of the digital humanities as they are practiced on non-English or multilingual texts.

Suggested Reading

Related Programming Historian lessons

The following lessons can help with other important aspects of working with textual data that can be applied to non-English and multilingual texts.

-

Corpus Analysis with spaCy: This lesson is an in-depth explanation of how to analyze a corpus using spaCy, and goes into more details of spaCy’s capabilities and syntax. This is a highly recommended read if you plan to use spaCy for your work.

-

Normalizing Textual Data with Python: This lesson explains various methods of data normalization using Python, and will be very useful for anyone who needs a primer on how to prepare their textual data for computational analysis.

Other resources about multilingual text analysis and digital humanities

-

Multilingual Digital Humanities: A recently published book covering various topics and projects in the field of multilingual digital humanities, featuring a broad range of authors and geared toward an international audience. (Full disclosure: I have a chapter in this.)

-

multilingualdh.org: The homepage for the Multilingual DH group, a ‘loosely-organized international network of scholars using digital humanities tools and methods on languages other than English.’ The group’s GitHub repository has helpful resources as well, including this bibliography and this list of tools for multilingual NLP.

-

Agarwal, M., Otten, J., & Anastasopoulos, A. (2024). Script-agnostic language identification. arXiv.org. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2406.17901: This article demonstrates that word-level script randomization and exposure to a language written in multiple scripts is valuable for script-agnostic language identification, and will be of interest for those looking to explore research literature on computational language identification.

-

Dombrowski, Q. (2020). Preparing Non-English Texts for Computational Analysis. Modern Languages Open, 1. https://doi.org/10.3828/mlo.v0i0.294: This tutorial covers some of the major challenges for doing computational text analysis caused by the grammar or writing systems of various non-English languages, and demonstrates ways to overcome these issues. It will be very helpful to those looking to further expand their skills working with computational text analysis methods on non-English languages.

-

Dombrowski, Q. (2020). What’s a “Word”: Multilingual DH and the English Default. https://quinndombrowski.com/blog/2020/10/15/whats-word-multilingual-dh-and-english-default/undefined.: This presentation, given at the McGill DH Spectrums of DH series in 2020, provides a great introduction to the importance and value of working with and highlighting non-English languages in the digital humanities.

-

Velden, Mariken A. C. G. van der, Martijn Schoonvelde, and Christian Baden. 2023. “Introduction to the Special Issue on Multilingual Text Analysis.” Computational Communication Research 5 (2). https://doi.org/10.5117/CCR2023.2.1.VAND: This issue will be of interest to those looking for research applications of multilingual text analysis, or who are interested in surveying the state of mutlilingual text analysis in contemporary academic literature.