Contents

- Lesson Overview

- Initial Considerations

- Building a Gazetteer from a Historical Text

- Preparing a Gazetteer for Mapping with Modern Software

- Using Linked Open Data and GIS Mapping to Enhance a Gazetteer

- Related Programming Historian Lessons for Future Study

- Conclusion

- Endnotes

Lesson Overview

The term gazetteer refers to certain geographical documents, such as indexes, directories, and encyclopedias, that were historically printed1 – this lesson is focused on their digital equivalents. Digital gazetteers record names, spatial footprints, and other characteristics associated with specific places. Historical gazetteers, in particular, link discourses about one or more places over time.

A gazetteer, especially a historical one, is a kind of Knowledge Organization System (KOS), a tool ‘that brings together related concepts and their names in a meaningful way, such that users of the KOS can easily comprehend the relationships represented’.2 The shape and organization of this KOS will be determined by the shared characteristics of the places that need to be modeled.

Thus, in its briefest sense, a gazetteer is a dictionary or list of place names. However, a well-structured gazetteer reflects the fact that places are conceptual entities, not simply names or points on a map. For example, any given place may have had multiple names in numerous languages over the course of history, potentially involving conflicts about who has the power to enforce any of those names. The spatial extents, names, and feature types (settlements, buildings, nations, mountains, and so on) of places also frequently change over time.

This lesson teaches you how to leverage the power of digital gazetteers, which are essential resources for spatial history. Unlike maps, gazetteers can readily connect named spatial entities with one another and with their modern locations, and they make it easy to annotate any identified place with information about texts, events, people, or other places that have been associated with it.

Learning Outcomes

Throughout this lesson, you will learn how to think about the concept of place, why gazetteers are useful for spatial history, how to use historical information to create a gazetteer, and how to enhance and share a gazetteer.

This lesson will demonstrate how to build a digital gazetteer, starting with a simple spreadsheet that you can build into Linked Open Data resources to communicate with other projects. Linked Data is structured data that can be interlinked with other data to undertake large queries. Linked Open Data is Linked Data that is released under an open license, meaning that it can be reused for other projects. You can find out more about Linked Open Data in this Programming Historian introduction to linked data.

This lesson fulfills two components: first, demonstrating why and how a scholar might choose to build a basic gazetteer and, second, how a gazetteer can support historical analysis. At the end of this lesson, you will be able to:

- Understand the concept of place

- Define what a gazetteer is and distinguish it from other forms of spatial information

- Identify scenarios for which creating a gazetteer may be preferable to using a geographic information system

- Transform a historical text into a gazetteer

- Share a gazetteer with other platforms to enhance it and use it for analytical purposes

Prerequisites

No coding experience is needed to complete this lesson. You should simply be comfortable designing and using spreadsheets, and you will need access to a spreadsheet platform such as Microsoft Excel, Google Sheets, or LibreOffice Calc.

Example Case Study

This lesson will show you how to create a gazetteer based on the online Itinerary of Benjamin of Tudela, an English translation of a Hebrew-language itinerary composed by Benjamin of Tudela (1130-1173), a Jewish traveler who journeyed between the Iberian Peninsula and West Asia in the 12th century. Benjamin transited through 300 cities along his route, recording information about geography, ethnography, commerce, Jewish life, and Jewish-Muslim relations.3 This text is a major work of medieval geography and Jewish history. This lesson will teach you to extract place names from this written historical text and use them to build a succinct gazetteer of the places that Benjamin visited, including their historic names and other feature types which are essential to the historical record.

Initial Considerations

What is a Place?

You might think that a place is simply a geographic location. You’ll find it much more helpful, however, to think of it as a concept.

The geographer John Agnew postulated that when we say something is a ‘place’, we are talking about three different ideas. First, any place has a specific location. It lies somewhere on the surface of the Earth. Second, the place is a setting for social relations. A place is a locale that shapes values, attitudes, or behaviors: a workplace, school, or prison are examples of such locales. Finally, any given place has a unique sense of place for those who pass by or stay there, perhaps evoking specific sensations of belonging or unbelonging. In other words, a place is a location where memorable events have transpired.4

Cultural geographers like Yi-fu Tuan tend to distinguish the concept of place, with its references to unique and distinctive settings for human activity, from that of space, which refers to the totality of all possible geographical expanses, many of which may exist regardless of whether they are sites of human meaning.5

Many theorists of place describe the concept in historical and temporally dynamic terms. The Marxist feminist geographer Doreen Massey defines places as sites of ‘meeting up of history in space’, in which people with different relations to authority and security encounter one another.6 The anthropologist Tim Ingold emphasizes the fact that ‘places do not just have locations but histories’, because they are networks of habitation where peoples’ pathways become entangled.7 The Black activist geographer Ruth Wilson Gilmore underscores the fact that struggles for social justice are always spatial, and thus they are always about processes of place-making.8

For these scholars, place can never be distinguished from travel, activity, relations of power, and human interaction. With its focus on human activity, meaning, contestation, and change over time, ‘place’ (the purview of names, lists, descriptions, and gazetteers) is often a more meaningful concept for spatial historians than ‘space’ (the domain of maps, which cannot easily represent human interaction and meaning). Place is an essential concept for many types of historical analysis, as well as many types of data curation.

The set of values, institutions, and relationships associated with any given locale are multitudinous, dynamic and unstable. A place may change substantially in all its particulars, even as it persists as a spatial entity. Names for places may coexist, or they may succeed each other according to regime changes or major events. Constantinople (also known historically as Lygos, Byzantium, Nova Roma, Rūmiyyat al-Kubra, and many other aliases) took on the name Istanbul after the Ottoman conquest of the city in the fifteenth century, though both names were used officially until 1928. When Dutch settlers colonized the ‘hilly island’ at the mouth of the Hudson River, which the Native American Lenape residents called Manahatta, they named their settlement Nieuw Amsterdam – this became New York in 1664, after the English took over the Dutch colony. Informally, people might also refer to the city by the 1807 term Gotham, or the 1921 term Big Apple. If they are speaking or writing in Chinese, they would call it Niuyue (纽约).

Conversely, places may retain stable names even as their spatial footprints change: for instance, when rivers break their banks and take new courses, or when metropolitan areas expand their boundaries. Even though the mappable extent of a river may change over time, the river persists as a fixed conceptual entity in the minds of the people who navigate it, reside near it, or read, write, and talk about it. The Yellow River is still the Yellow River even when it is dry, dammed, or flooded. From the perspective of knowledge modeling in a gazetteer database, the river is a single entity, associated with a large cluster of attestations that are specific to certain events and time periods.

Gazetteer or Geographic Information System (GIS)?

The first task for anybody embarking on a digital spatial history project is to decide whether to begin with a dataset-based gazetteer, or a map-based Geographic Information System (GIS).

A project emphasizing the conflicting, contested, and dynamic characteristics of places, as well as spatial information reflected in textual attestations, should begin with a gazetteer. An example of such a project would be the Heritage Gazetteer of Libya, which aims to provide information about unique identifiers, locations, and monuments within modern Libya that were important to its history before 1950. The emphasis of this project is on compiling names and variants produced by the research of the Society for Libyan Studies.

A GIS is only the logical starting point for a spatial history project centered on geography and spatial relations per se. Both gazetteers and GIS are based on spatial data structured in particular formats, but the focus of a GIS is primarily on the projection of geospatial geometries, in the form of points, lines, and polygons. An example GIS project would be the Bomb Site: Mapping the WW2 bomb census project, which prioritizes the visualization of targets of the Luftwaffe Blitz bombing raids in London from October 7, 1940 to June 6, 1941. While a gazetteer may also contain geographical information, its primary focus is on depicting more information about places then merely points, lines, or polygons on a map base.

Indeed, although geometry is necessary for making maps, the symbols on maps only tell a small part of the story of a place. The way to model rich, multivocal data about place-making events and contestations of power, about places as settings for social events, and about the sense of place and its representations, is with a gazetteer, not a map. Gazetteers are excellent for collecting information about what a place has been called, by whom, why, and when; who has been there; what has occurred there; who has contended for authority over it; or what texts have referred to it. Gazetteers often use a controlled vocabulary to designate the supplementary feature types associated with places: whether a place is a settlement, a waypoint on a travel itinerary, or a geographical feature such as a mountain or river.

These questions are all of special interest to historians. In many cases, a gazetteer is actually a more useful way of capturing and analyzing historical spatial information than a map. In its simplest form, a gazetteer is an index or dictionary of place names, and does not need to include geographic coordinates (although many do so, to help visualize the spatial data). Gazetteers, thus, are not merely limited to the historical realm: they could also be used to trace the movements of a character across a fictional realm, like Frodo’s travels from The Shire to Mordor.

Grouping Different Place Names Together

By this point in the lesson, it should be clear that the most important consideration is to recognize that place is the fundamental entity in any well-designed gazetteer, over and above individual place names, or attestations of the existence of a place at a certain date in a particular source document.

The author of a historical gazetteer which includes information about New York, the great metropolis situated at the mouth of the Hudson River, would do well to group information about its many names into one complex entity associated with a single ID number: Lenape Manahatta, Dutch Nieuw Amsterdam, British colonial New York, and Washington Irving’s 1807 coinage of Gotham.

Grouping multiple names and attestations into a single gazetteer record allows for several affordances. First, it turns the gazetteer into a powerful thesaurus. Second, it makes it possible to map as much information as possible onto a single geographical referent. Third, it makes the gazetteer a compelling (and potentially decolonial) work of history which tells a story of sovereignty, colonialism, and culture. Finally, it improves search and discovery, especially in the context of Linked Open Data.

Names and attestations that are grouped into a single entity are easiest to find and use, but the decision to group disparate pieces of information may come at the expense of precision, accuracy and nuance. The author or team working on a gazetteer may therefore choose to articulate certain disambiguation principles to allow better interoperability and reusability of the data. Beyond human judgement, these questions are the domain of entity resolution, which is an open and unresolved topic in information science, natural language processing, and geoscience.9 Spatial historians, as well as information scientists interested in questions of temporality, have also begun to publish on this topic.10

To be sure, it is a matter of your personal and scholarly judgement, and of your research strategy, to decide whether these names do indeed refer to a single place. After all, Manahatta was the name of an island, not an inhabited place, and that island today is the site of only one of the five boroughs of New York City. There is no objective way to decide whether to group these names together as references to a single place. In an ambiguous case like this, whether you group these names together or not is determined primarily by whether it would enhance your research inquiry and visualization tasks to do so. Alternatively, you could keep these names separate, but still define them as ‘relations’ using a Linked Places format, or another similar data format.

LP and LP-TSV Formats

In this lesson, we’re building a gazetteer using the Linked Places Delimited (LP-TSV) format to simplify future data interoperability. LP-TSV is a file format derived from the Linked Places (LP) format, a standard for interconnection used when contributing historical place data to Linked Open Data projects. The LP format permits temporal scoping of entire place records and of individual name variants, geometries, place types, and place relations, expressed either as timespans or as named time periods.

LP-TSV does also support any number of names, geometries, and relations, as well as information about the sources of such assertions. However, this file format is intended for gazetteer developers whose data is relatively simple: for example, while an LP-TSV row can provide the timespan of an entire record, it does not permit temporal scoping of individual components of the record.

LP-TSV is widely used for historical gazetteers, and we suggest you adhere to this standard from the onset. Using an established standard like this means that the data you create in this lesson, or that you create for your own research using this lesson, can be shared with other like-minded researchers to create new knowledge. It might seem cumbersome at first, but it will save you lots of time if you do decide to share this project later.

Building a Gazetteer from a Historical Text

Historians often work with detailed written texts, such as memoirs or travelogues, that may contain a wealth of spatial information. The Itinerary of Benjamin of Tudela is one such example of a rich, descriptive historical text that can be data-mined for spatial research.

Benjamin of Tudela was a 12th century Spanish Jewish traveler whose text describes his expedition and his interactions with different Jewish communities along the way. A spatial historian interested in this text may want to discover where Benjamin of Tudela traveled on his grand journey, and how he interacted with Jewish communities in the locations he visited. In fact, these are the research questions that we will actively explore in this lesson’s example case study.

A scholar might also use this source as one element in a larger corpus of texts to examine questions about travel in the post-classical period, European exploration, or Eurasian Jewish studies. The places named in this itinerary could be cross-referenced with those named in other accounts from a similar period to see if certain stops were more popular than others, or how different travelers described the same locations.

The structure of Tudela’s travelogue suggests the outline for a gazetteer spreadsheet. The authors of this lesson recommend using either Microsoft Excel or Google Sheets for the process of creating a simple gazetteer that is compatible with the LP-TSV format.

To begin, navigate to the section entitled ‘The Itinerary of Benjamin of Tudela’ on the web version of this text.

Creating the Spreadsheet’s Fields

The first task is to create a spreadsheet and determine the fields that you will populate with data taken from the historical text. Open Excel, or your preferred spreadsheet software.

In a widely cited 2006 book, the geospatial librarian Linda Hill suggested that each entry in a well-structured gazetteer should include at least one name, at least one set of coordinates, and one or more feature types.11 For historians, it is especially important to include modern place names if the name has changed, as well as the temporal range of the older name(s) attested in a source. With multilingual sources or projects, it may also be important to note different names or transliterations for a given place: for example, Moscow (EN), Moskau (DE), Moscou (FR), Москва (RU). In keeping with good practices for creating spreadsheets that may need to be shared or exported into other software, you should always include an ID number column. Start by naming the first column ID.

From the first paragraph of The Itinerary, we understand that we need a column for the place names of travel stops: call the next column TravelStop. You could use whatever column headers you want for your own research, but the LP format recommends the use of a ‘place type’, so add a column called PlaceType. You will also include a column for ‘attribute type’, another strongly recommended standardized form of attribute data that makes it easier to share historical spatial project data. Type in aat_type in the next column.

Since the research question for this lesson also revolves around Jewish history, you should add a column to mark whether the place has a Jewish population. Call this column JewishPop. You might want to add a column that allows you to include further descriptions of the Jewish population, if there are any.

There are two other columns you should add: one that accounts for where you got this spatial information – call this column Source. The other, called AttestedDate, will record when a particular name was used to call the place in question.

For now, your spreadsheet should look something like this table below:

| ID | TravelStop | Source | AttestedDate | PlaceType | aat_type | JewishPop |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Formatting Considerations for Data Portability and Interoperability

You are formatting your column headers in this way to help with future data interoperability. If you were to export your data to mapping software like QGIS or ArcGIS, you would need the ID column. Mapping software also does not like long column headers. ArcGIS, for example, can crash if a column header includes spaces or is longer than 15 characters. Try to think of the shortest way to name columns that will make sense to you and potential future collaborators.

Another important note to keep in mind when building spreadsheets for data interoperability is not to use commas: many programs you might rely on for future analysis will require that the spreadsheet be uploaded in .csv (comma separated value) format. This means that anytime the software sees a comma, it reads it as the boundary of a cell or row in the spreadsheet. Inserting commas will break the software and make the sheet unreadable. If you need a way to parse information, use a semi-colon. A good rule of thumb is to avoid most special characters whenever you can, since they can also break the software. If you need to put a space in a column header, use an underscore.

You may wish to keep a separate data dictionary to store information about your abbreviations and other data management decisions. If you briefly describe what makes your specific columns important, your research becomes a more valuable contribution to linked scholarly projects. Other researchers will be able to understand your editorial choices for data management and make better use of your data in their projects. Citing your sources and including historical information about when they were written in your data dictionary will also make it easier to extend your gazetteer in the future. Indeed, you might only use one source at the moment, like The Itinerary, but if you later add other travel accounts to the gazetteer, it will then be important to parse out who used which name variant, and when.

Adding Historical Data to the Spreadsheet

You are now going to enter the information you find in the first paragraph of Tudela’s travelogue into your spreadsheet. By starting only with the first paragraph, you’ll see whether your model works well or needs any changes. It’s better to test with a smaller sample of data and tweak it earlier rather than later.

-

Fill in the data that corresponds to the column headers you have already created. Go through the first paragraph of the text and enter each stop name into the TravelStop column.

-

Use controlled vocabulary to describe the travel stop locations. In the PlaceType column, type ‘inhabited place’, which is a standardized vocabulary term from the Getty Art and Architecture Thesaurus, a structured resource that aims to improve access to information for art, architecture, and material culture. It is extremely useful for history projects as it is a well-established, controlled vocabulary that is used by a variety of different scholars and projects across a multitude of humanistic and social science disciplines.

-

Fill in the aat_type column with the aat code for inhabited place, ‘300008347’.

-

Confirm the presence of Jewish populations in these travel stops in the JewishPop column. For simplicity’s sake, and for future data sorting, write ‘Y’ or ‘NA’ (not applicable) rather than ‘N’ (for no), since you don’t want to propagate false information about whether there was definitively a Jewish population solely based on this account.

-

Describe the data’s source: in the Source column, record that your information comes from The Itinerary. You can abbreviate the name of the source as you wish and maintain the full citation in a separate data dictionary document. For now, you can write ‘ItineraryTudela’. It is essential for digital spatial history projects like this to rigorously maintain the same standards of citation that are expected from any other work of historical scholarship. Recording this information in the spreadsheet itself, rather than in the external metadata, will also make it easier to add records from other sources if you expand your research in the future.

-

Since this project is related to historic naming conventions, you need to account for variations in time in your AttestedDate column. In this column, write the year during which the place name was presumably correct. In our example, Benjamin set out on his journey around 1165, but The Itinerary does not record the specific dates of Benjamin’s sojourns in each place he visited. It is also not clear exactly when he composed The Itinerary, though we know that he died in 1173. We recommend that you choose the arbitrary date of 1170, with a note in your data dictionary and your metadata indicating that this is an estimate.

In some gazetteers, it’s possible to ascribe precise start and end dates to specific elements (such as the dates during which a certain place name was in official usage, or the dates during which a place held a particular administrative status, or during which a river followed a precise course). More often, though, when historians build gazetteers from specific historical sources, all they know is that the author of that source recorded the existence of a place at a given time: the existence of the place is attested in a source. Over time, in a Linked Open Data resource like the World Historical Gazetteer (WHG), which indexes multiple gazetteers in one, it becomes possible to build up multiple attestations into a history of a place.

The full LP format allows you to add temporal information to every aspect of a complex gazetteer record. Multiple names, locations, and feature types associated with a given record can each include start dates, end dates, and attested dates. For a simple spreadsheet like the one you are making in this exercise, though, it is cumbersome to include extensive temporal information.

It is still always a good idea to include some form of temporal information in a gazetteer, and the LP-TSV format requires that you include at least one date. If you find that you have no relevant temporal information to record, you can use -9999, which is the oldest possible year that many database systems can parse.

- Finally, number each of your entries sequentially in the ID column, starting with 1.

If you follow the model we outlined, your spreadsheet should look something like the table below:

| ID | TravelStop | Source | AttestedDate | PlaceType | aat_type | JewishPop |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tudela | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | NA |

| 2 | Saragossa | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | NA |

| 3 | Tortosa | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | NA |

| 4 | Tarragona | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | NA |

| 5 | Barcelona | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | Y |

| 6 | Gerona | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | Y |

| 7 | Narbonne | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | Y |

| 8 | Beziers | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | Y |

| 9 | Har Gaash | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | Y |

| 10 | Lunel | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | Y |

Uncovering New Research Questions

An additional benefit of a gazetteer project is that it is highly iterative: while an initial research question or two about the source will lead to a preliminary structure, the act of recording simple amounts of data can actually serve to generate various follow-up research questions.

In this case, a researcher might now want to know more than just which settlements had some sort of Jewish population. They could, for example, look into the size of the populations in various settlements. In the case of Narbonne, Benjamin gives a figure of 300 Jews. In the cases of Barcelona and Gerona, he gives no number, but he describes either a ‘holy’ or ‘small’ congregation, which are clues to the size of the Jewish communities there. A researcher could then ask questions to know more about cities which had large, small or no Jewish populations. For example, they could see whether certain cities were centers of Jewish education.

The gazetteer has already generated a wealth of important information and subsequent questions. A researcher will probably wish to create new columns and enter all the different types of information collected about the Jewish populations (i.e., congregation size, educational facilities, number of Rabbis listed, etc.) to make this data easier to filter and analyze later. The steps below outline how you might want to do this.

-

You’ll need to start by augmenting your spreadsheet. Add a column called DescJewishPop, in which you can record Benjamin’s descriptions of the local population. After creating this column, go back to the text to find the relevant data you want to add to the spreadsheed.

-

The second paragraph of the travelogue clues us into another important column: name variants. Benjamin mentions a settlement called ‘Har Gaash’, which he notes has the alternative name ‘Montpellier’. You should record both names, as other sources might only list one of them, so this gazetteer could serve as a means to reconcile the two around the same physical location. Insert a column after TravelStop and call it AltName, where you’ll enter ‘Montpellier’ in the row for ‘Har Gaash’.

-

Continue processing the itinerary through to the end of the third paragraph. That will provide sufficient information for the remaining steps of this lesson. If you do not wish to continue building the spreadsheet further after that, you can download a final version of the information found in the first three paragraphs here.

If you have typed in the information yourself thus far, you spreadsheet should look like the table below.

| ID | TravelStop | AltName | Source | AttestedDate | PlaceType | aat_type | JewishPop | DescJewishPop |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tudela | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | NA | ||

| 2 | Saragossa | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | NA | ||

| 3 | Tortosa | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | NA | ||

| 4 | Tarragona | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | NA | ||

| 5 | Barcelona | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | Y | holy congregation; sages; 4 rabbis | |

| 6 | Gerona | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | Y | small congregation | |

| 7 | Narbonne | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | Y | learning center; Torah; sages; 4 rabbis; distinguished scholars; 300 Jews | |

| 8 | Beziers | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | Y | congreation; rabbis | |

| 9 | Har Gaash | Montpellier | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | Y | scholars; rabbis; learning centers; Talmud |

| 10 | Lunel | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | Y | congretation; Israelites; learning centers; law; rabbis; Talmud; Sephardi; 300 Jews |

You could continue to extend this gazetteer with information from the rest of the text, which will probably generate more research questions and data points to analyze. Even from the section you have processed so far, though, you now have information about 12th century Jewish history that is connected to space and place. Those who compile data such as this might also want to map the data, which leads to one of the greatest challenges of historical-spatial research: mapping historic place names using modern software.

Preparing a Gazetteer for Mapping with Modern Software

Major mapping software providers like Google Maps tend to have knowledge of major name changes such as Stalingrad/Volgograd or Bombay/Mumbai, but they usually lack more obscure historic data. Tudela, from our dataset, is on Google Maps because the name has not changed since Benjamin’s journey. Google Maps also knows that Saragossa is an alternative spelling for Zaragoza, which is how the name now appears on the map. Without Google performing this automatic reconciliation, you might not know this to be the same place.

Thus, you’ll need to work additional columns into your spreadsheet to help map this information.

-

Create the columns ModName (modern name), Latitude, and Longitude.

-

You should also add a column to log the ISO code of the modern country where this location exists. This is a two-letter code created by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and used as an internationally recognized standard for referring to countries. They’ve also created a three-letter code series, but it’s generally easiest to use the two-letter codes. Create a column called ISO.

Using ISO codes is important for many spatial projects (including this one) because, while many place names may be unique in the world, others, like Barcelona and Montpellier, are not. The code therefore allows you to specify the correct geographic location you are referring to. Moreover, since this is a travelogue of a journey from Spain to Jerusalem, you know that our traveler will be traversing the lands of numerous modern countries. You may wish to ask further research questions about that, so it is better to log the information consistently as you go along. The table below illustrates the progression of the spreadsheet so far.

| ID | TravelStop | AltName | ModName | Latitude | Longitude | ISO | Source | AttestedDate | PlaceType | aat_type | JewishPop | DescJewishPop |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tudela | Tudela | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | NA | |||||

| 2 | Saragossa | Zaragoza | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | NA | |||||

| 3 | Tortosa | Tortosa | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | NA | |||||

| 4 | Tarragona | Tarragona | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | NA | |||||

| 5 | Barcelona | Barcelona | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | Y | holy congregation; sages; 4 rabbis | ||||

| 6 | Gerona | Gerona | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | Y | small congregation | ||||

| 7 | Narbonne | Narbonne | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | Y | learning center; Torah; sages; 4 rabbis; distinguished schoars; 300 Jews | ||||

| 8 | Beziers | Beziers | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | Y | congreation; rabbis | ||||

| 9 | Har Gaash | Montpellier | Montpellier | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | Y | scholars; rabbis; learning centers; Talmud | |||

| 10 | Lunel | Lunel | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | Y | congretation; Israelites; learning centers; law; rabbis; Talmud; Sephardi; 300 Jews |

You might also be interested to see if the places named in his journeys are different today. Where would you go to find the modern names of those places? There are a multitude of options for this, but the easiest to use is the WHG website, a project which works to reconcile historic place names around the globe with their modern variants, across a multitude of languages and alphabets.

-

Navigate to the website and press the Explore open access, historical place data button, or click here to be taken directly to the search interface.

-

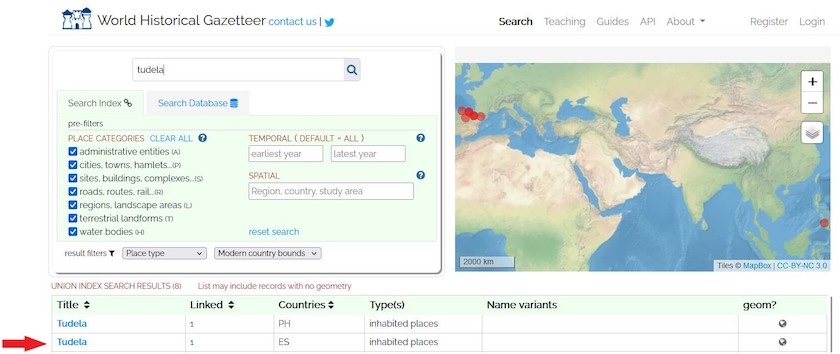

Let’s start with the first location, Tudela. Type ‘Tudela’ into the search box and inspect the few results given. You know that Benjamin of Tudela is a Spanish traveler, so the result you’re looking for is the second option, Tudela in ‘ES’ (for Spain).

Figure 1. World Historical Gazetteer search results for ‘Tudela’.

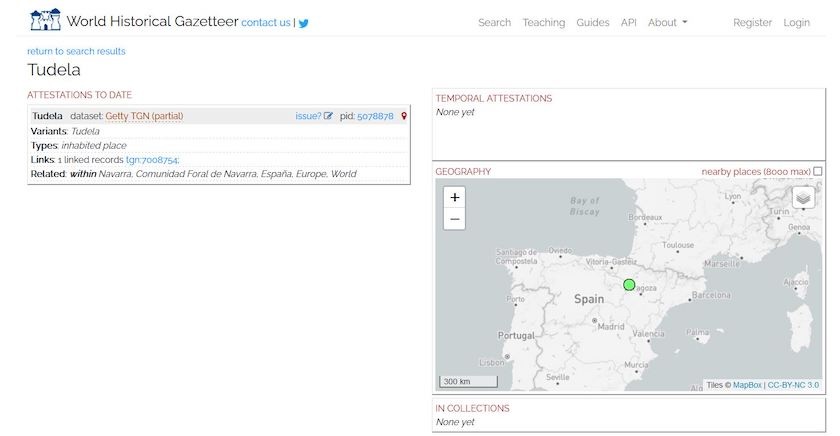

- Click on this record to open a new window. You can see that the WHG indicates no other variants for the place name Tudela (ES), so you can assume the city is still called Tudela. You can always verify this with a Google Maps search.

Figure 2. Tudela record in World Historical Gazetteer

-

The WHG also provides the city’s geometric coordinates, which you can find by clicking on the green dot showing its location on the map. This should open a new pop-up indicating the latitude and longitude. Make sure you copy and paste both the country code (from the search page) and the latitude and longitude coordinates into your spreadsheet.

-

If you search the next record in your spreadsheet (Saragossa), you’ll learn that its modern name is Zaragoza. Again, you can capture the country code and latitude and longitude information from the WHG. If you follow these steps for the rest of the sample cities, your spreadsheet should look as follows.

| ID | TravelStop | AltName | ModName | Latitude | Longitude | ISO | Source | AttestedDate | PlaceType | aat_type | JewishPop | DescJewishPop |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tudela | Tudela | 42.083333 | -1.6 | ES | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | NA | ||

| 2 | Saragossa | Zaragoza | 41.633333 | -0.883333 | ES | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | NA | ||

| 3 | Tortosa | Tortosa | 40.8 | 0.516667 | ES | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | NA | ||

| 4 | Tarragona | Tarragona | 41.116667 | 1.25 | ES | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | NA | ||

| 5 | Barcelona | Barcelona | 41.398371 | 2.1741 | ES | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | Y | holy congregation; sages; 4 rabbis | |

| 6 | Gerona | Gerona | 41.982548 | 2.822449 | ES | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | Y | small congregation | |

| 7 | Narbonne | Narbonne | 43.184417 | 3.008816 | FR | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | Y | learning center; Torah; sages; 4 rabbis; distinguished schoars; 300 Jews | |

| 8 | Beziers | Beziers | 43.345287 | 3.222374 | FR | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | Y | congreation; rabbis | |

| 9 | Har Gaash | Montpellier | Montpellier | 43.587 | 3.9073 | FR | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | Y | scholars; rabbis; learning centers; Talmud |

| 10 | Lunel | Lunel | 43.675482 | 4.136189 | FR | ItineraryTudela | 1170 | inhabited place | 300008347 | Y | congretation; Israelites; learning centers; law; rabbis; Talmud; Sephardi; 300 Jews |

You can also download the filled-out spreadsheet here.

Now that you have all the modern equivalents, you’re in a good place to conduct additional research. For example, do these places still even exist? Has their identity changed over time? Have Jewish populations remained in these settlements? Have they grown, or reduced?

Using Linked Open Data and GIS Mapping to Enhance a Gazetteer

Simple gazetteers collect basic information about the names, feature types, and locations of places attested in historical texts. They can be enriched with further annotations (as you did by describing the Jewish populations in given settlements) and they can be linked with one another (as you did when you linked historic names with modern names and geometries). If you want to perform new investigations, for example into medieval Jewish history, you can also enhance the gazetteer you made about Benjamin of Tudela’s travels by connecting it to larger collections of linked spatial data. As we mentioned earlier, the best way for your research to enter into conversation with others and to benefit from analytical tools is to commit to Linked Open Data standards.

You already used the WHG to search for historic place names and to find coordinates for your spreadsheet. You could have used the affordances of the Linked Open Data standard to upload your earlier spreadsheet into the WHG, create a map of your places, and download an augmented spreadsheet containing the geographic data. More information on how to do that can be found in another Programming Historian lesson.

You can also choose to publish your datasets through the WHG and reconcile them against Wikidata or the WHG index itself. Publishing on the WHG permits you to enhance the WHG datastore, and it also allows you to collect information that the WHG already holds about your target places. Indeed, WHG place records are concatenations which can link different attestations about the same places from multiple gazetteers. This a good way to manage the impossibility for a single gazetteer to contain all the relevant information about a given place.

You can also annotate places indexed in the WHG to create Collections, which you can read more about on the WHG website. Collections allow you to record complex information about places, to link places to one another based on a theme of your choosing, and to drive traffic from the WHG to any website you identify.

Once you have geographic information (e.g. latitude and longitude coordinates), you can also make a variety of maps to visualize this information using desktop or web-based GIS software. Using the data you created in this lesson, for example, you could produce a map showing all (or a subset of) the places through which Benjamin of Tudela traveled using QGIS, an open-source desktop software for making GIS maps. You can get started with it using this Programming Historian lesson.

Related Programming Historian Lessons for Future Study

Readers might find some other Programming Historian lessons to be of use, in addition to the related lessons mentioned above. For example, once you have a gazetteer, you can also use it for text analysis projects: you could run your list of names through a corpus (or corpora) to automatically find attestations of those same locations in other sources. An example of this would be to compare the locations attested in Benjamin of Tudela’s travels with other contemporary travelogues, to find out which locations were the most important in medieval travels. This Programming Historian lesson will run you through extracting keywords from your gazetteer.

Readers might also find the steps in the Geoparsing English-Language Text lesson useful if they merely need to extract a list of place names mentioned in a text, without any additional attribute data.

In addition to using either QGIS or the WHG to map the data produced in this lesson, readers might be interested in learning how to use R for geospatial data and historical research.

Conclusion

Recent scholarship has emphasized that the field of spatial history is not synonymous with the domain of historical GIS.12 Indeed, the intellectual history of spatial representation reflects the fact that maps have not usually been the most widely used tools for recording information about the geographical settings for human activity.13 Even today, when we use navigation apps to find directions to destinations, for example, we are interacting with gazetteers, not reading maps. Despite these insights, education for spatial history tends to focus almost exclusively on GIS training.

One purpose of this lesson has been to demonstrate why GIS may not be the best starting point for many spatial history projects, and to explain why you may want to begin with a gazetteer instead. In that spirit, we conclude with a checklist that may assist in determining the strategy that will work best for your project and your research objectives:

- Does your project include a corpus of places and their names, feature types, and locations? In that case, you are well on your way toward building a gazetteer.

- Do you want to track complex non-spatial information about places, such as multiple names, events that have occurred there, associated attributes, texts that refer to them, or rich narrative information about them? If so, a gazetteer is preferable to a GIS.

- Is temporal resolution important to your project? In a GIS, temporal information can be effectively represented only with timestamped layers. This may force you to combine temporal references that you would prefer to keep disaggregated, or to redundantly record information in multiple attribute tables. A gazetteer may be preferable in such cases.

- Do you intend to publish place information in a linked data domain that permits you to combine it with other people’s contributions? If so, you should create a gazetteer.

- Does your project involve geospatially complex information and complex spatial analysis (such as geostatistical analysis, spatial autocorrelation, or spatial clustering)? If so, you need to use GIS.

- Conversely, is the geospatial character of your data simple, or is spatial precision unimportant for your project? If you are working with point locations rather than polylines or polygons, a gazetteer may be adequate.

Finally, remember that gazetteers and GIS systems can be readily transformed into one another, once you understand the principles of place and gazetteer design that we have presented here. Named place information incorporated into GIS data can be exported and used as the basis for a more temporally and toponymically complex gazetteer; equally, a gazetteer that includes geospatial coordinates can be imported into a GIS to facilitate spatial visualization and spatial analysis.

Endnotes

-

Ruth Mostern and Humphrey Southall, “Gazetteers Past,” Merrick Lex Berman, Ruth Mostern, and Humphrey Southall, eds., Placing Names: Enriching and Integrating Gazetteers (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2016), 15-25. ↩

-

Ryan Shaw, “Gazetteers Enriched: A Conceptual Basis for Linking Gazetteers with Other Kinds of Information,” in Placing Names: Enriching an Integrating Gazetteers, ed. Merrick Lex Berman, Ruth Mostern, and Humphrey Southall (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2016), 52. ↩

-

The standard English translation, which is the one used for the link we have included in this lesson is Marcus Nathan Adler, The Itinerary of Benjamin of Tudela: Critical Text, Translation and Commentary (New York: Phillip Feldheim, Inc., 1907). A scholarly trilingual (English, Hebrew, Arabic) version of the Itinerary was recently published. The English text on that site is the Adler version. ↩

-

John Agnew, “Space and Place,” in John A. Agnew and David N. Livingstone (eds.) Sage Handbook of Geographical Knowledge (London: Sage Publications, 2011). ↩

-

Yi-fu Tuan, Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, Reprint Edition, 2001). ↩

-

Doreen Massey, For Space (London: Sage Publications, 2005). ↩

-

Tim Ingold, Lines: A Brief History (Routledge, 2016), 105-6. ↩

-

Ruth Wilson Gilmore, “Fatal Couplings of Power and Difference: Notes on Racism and Geography” in Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Brenna Bhanda and Alberto Toscano, Abolition Geography (Verso, 2022). ↩

-

Pasquale Balsebre, Gao Cong, Dezhong Yao, Zhen Hai, “Geospatial Entity Resolution,” Proceeedings of the ACM Web Conference 2022 (2022), 3061-71 https://doi.org/10.1145/3485447.3512026 ↩

-

For example J. T. Hastings, “Automated Conflation of Digital Gazetteer Data,” International Journal of Geographical Information Science 22.10 (2008), 1109-1127; Vincent Ducatteeuw, “Developing an Urban Gazetteer,” GeoHumanities ‘21: Proceedings of the 5th ACM SIGSPATIAL International Workshop on Geospatial Humanities (November 2021), 36-39; and Pawel Garbacz, Bogumil Szady, and Agnieszka Lawrynosicz, “Identity of Historical Localities in Information Systems,” Applied Ontology 16 (2021), 55-86. ↩

-

Linda Hill, Georeferencing: The Geographic Associations of Information (MIT Press, 2006). ↩

-

For example Ian Gregory and Alistair Geddes, Toward Spatial Humanities: Historical GIS and Spatial History (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2014). ↩

-

Michael Curry, “Toward a Geography of a World Without Maps: Lessons from Ptolemy and Postal Codes,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 95.3 (2005), 680-691. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.2005.00481.x ↩