Contents

- Overview

- Lesson Goals

- Part 1: Introduction to Simulations and Agent-Based Modeling

- Part 2: Programming Agent-Based Models with Mesa

- Part 3: Summary, Open Questions and Next Steps

- Endnotes

Overview

In this lesson, we will provide an introduction to a simulation method called ‘Agent-Based Modeling’ (often abbreviated to ABM), via an Agent-Based Model of a historical letter-sending network, implemented with the Python package mesa.

The historical case that inspired this lesson is the ‘Republic of Letters’, an early modern network of scholars who wrote to each other extensively, thereby fertilizing each other’s thinking. It has already been extensively studied with digital methods12. Using our Agent-Based Model, we want to better understand the social dynamics of this correspondence network and how it was able to shape the scientific thought of the time.

The model we will build together is relatively basic, featuring only simple interactions like sending letters. Those simple interactions will lead to correspondence networks that are structurally similar to those observed in actual, historical datasets on letter sending.

The model we build here will not be sufficiently complex to give genuinely valuable perspectives on this case study on its own, but it will highlight some key properties of ABMs, and various ways to implement them. Crucially, by the end of this lesson, you will be able to extend the model further with more complex functionalities.

In the first part, you will learn what historical simulation methods are all about, their methodological and epistemological quirks, and how to start applying Agent-Based Modeling to your own research.

In the second part, you will follow a step-by-step guide to building your first Agent-Based Model, using the Python package mesa. This will be accompanied by further comments and reflections on the methodology of Agent-Based Modeling.

In the third part, you will explore ways to extend the model and further enhance your expertise in building Agent-Based Models.

Lesson Goals

This lesson intends to:

- Teach conceptual basics of simulation methods and ‘Agent-Based Modeling’

- Teach fundamentals of the Python package mesa for programming Agent-Based Models

- Give you guidance and resources for extending your Agent-Based Modeling knowledge beyond this tutorial

- Give an overview of methodological and epistemological caveats, challenges, and considerations when programming your own historical Agent-Based Model

Users of different skill levels and interests will find this lesson useful, for example if:

- You are completely unfamiliar with simulation methods and Agent-Based Modeling, and want a thorough introduction

- You already have a conceptual understanding of Agent-Based Modeling, and are wondering whether it could be useful for your own research project

- You already know that Agent-Based Modeling might be useful for your research, and now want to learn the modeling and technical implementation processes

- You are familiar with all of the above and need a starting point for implementing Agent-Based Models with mesa

Technical Requirements

For this lesson, mesa and its dependencies are necessary. Additionally, we will use matplotlib for visualizations and numpy for some calculations. Note that a solid understanding of Python is required for this lesson! If you are unfamiliar with features such as classes, tuples, list comprehension, and nested for-loops, but you do have previous Python experience, you could head over to w3schools to get up to speed. If you would like to have a more gentle and comprehensive introduction, head over to the Programming Historian introduction to Python. You could also follow this lesson using Jupyter Notebooks and read the corresponding introduction to Jupyter Notebooks.

If you want to follow this lesson on your local machine, you need to set up an environment with mesa installed. If you do not know how to do this, we have a simple step-by-step guide, which we compiled for a workshop. If you don’t already have Python installed on your local machine, you could read up on its installation for Linux, Mac or Windows in the corresponding Programming Historian lessons.

Execute the code block below in a command line (or in a Jupyter Notebook) to install mesa and its dependencies. If you already have Python (version >=3.9) installed, running the following code in a terminal should give you a new virtual environment with the mesa package, keeping this installation separate from your main system:

Python3 -m venv env

source env/bin/activate

pip install 'mesa>=2.4.0,<3.0'

Note that this installs a specific mesa version (2.4), for which this lesson was built. Future versions of mesa might require changes in the code.

try:

import mesa

except:

!pip install 'mesa>=2.4.0,<3.0'

Part 1: Introduction to Simulations and Agent-Based Modeling

1.1 Why use Historical Simulations for our Case Study?

In this lesson, we want to better understand the social, material and cognitive dynamics that shaped intellectual networks of the past, specifically during the early modern period. In this time in Europe, a primarily letter-based network of scholars of different nationalities emerged, often referred to as the ‘Republic of Letters’. The effect of this network on the history of science in Europe and the world is deemed to be pivotal.3 To understand these types of networks, it is not enough to study their shape and speculate about the historical sources we have about them. It is also essential to ask ourselves how exactly these networks came to be shaped as they were.

Questions related to this are usually hard to answer in a systematic and methodologically sound way. Consider for example the following questions:

- ‘Which social and intellectual dynamics led to some people playing a more central role in the network?’

- ‘How did people form and develop their connections in the network?’

- ‘What effects did limiting elements such as distance, infrastructure and technology have on the shape of the network?’

We can pose some limited hypotheses regarding those questions, and we might draw on sources to find some hints and correlations, but it is hard to reliably test those hypotheses.

One of the main motivations for using historical simulation, or even simulation in general, is precisely this: operationalizing hypotheses about the underlying reasons for (historical) phenomena, and comparing them against what we observe in reality. This means we’ll create a simulated version of our network example (based on our historical hypotheses), then check how its structure compares to the actual historical network. That way, we can test whether our hypotheses can explain the observed phenomena.

We could for example assume that, in a particular historical letter network, famous people receive a higher amount of letters, and that this is a self-reinforcing effect. Or, we could consider it more likely that a person will prefer to send a letter to a close neighbor rather than to someone far away. We can also hypothesize about the effect of the letters’ topics. For example, letters might more likely be sent if a sender agrees with a receiver’s personal opinion – although the opposite could arguably turn out to be true.

Building a simulation model of this letter network will allow us to represent different hypotheses about its dynamics, giving us a more thorough understanding of its workings. But what does it actually mean to build a simulation?

1.2 What are Simulations?

To start off, we want to give you a very general definition of the term ‘simulation’:

“The term ‘simulation’ describes a number of different methods of model-based, experimental reproduction of a real-world or hypothetical process or system.”4

As the definition says, the basis of every simulation is an executable simulation model. This class of models - similar to data models - can be expressed conceptually (i.e. with more or less stringent language), logically (i.e. in logical terms of ‘if-then’ ‘is/is not’ etc.) or mathematically (i.e. through mathematical terms). To execute a simulation model, however, it must be formalized (i.e. converted into computer-readable form). Just as for a data model, we must find ways to formally represent our ideas of person, place, and event (such as a letter exchange). Additionally, we’ll also need to describe triggers for certain actions, movements, and interaction rules.

We can then run the simulation to see how these interaction rules play out together over time. Once we’ve noted these new pieces of information - essentially, the model outputs – our model can be revised and run again. The process of building a simulation model therefore involves constant iteration, cycling between the phases of running the model, interpreting the results, and then adapting the model for further experiments. In this sense, simulation methodology is comparable to the hermeneutic circle of heuristics, critique, and interpretation, which historians are familiar with.5

Before we move on, let’s come back to the part of the definition mentioning ‘real-world or hypothetical’ subject matters. Many historians probably hold a cautious view of the nature of historical reality and - more importantly - our ability as scholars to describe it. Just as sources are king in traditional history, data is queen in digital history.6

However, as we’ve hinted at already, the objects of a simulation are not simply data: rather, they encompass all our hypotheses about history, i.e. all the assumptions we have about the past that we believe connect our data into a plausible narrative. By building a historical simulation model, we are automatically moving ‘from the actual to the possible’.7

The alluring – yet tricky – opportunity afforded by historical simulations is therefore to move between and beyond the actual data we have at our disposal in a formalized way. One crucial difference between this and the epistemologically similar, traditional counterfactual approaches to history is the formalized, systematic and experimental/iterative nature of simulations.

One last important caveat left to mention about definitions of simulation methods: there are many definitions, and discussions about which is the most suitable are currently in progress, especially in history! A definition sometimes depend more on what its goals are (e.g. educational or scientific, see note below). Sometimes, definitions of simulations will avoid encompassing certain applications, in order to avoid some of the epistemological challenges posed by historical studies.8 We have opted to present to you one of the more open and general definitions of simulations, for clarity’s sake, and to avoid the epistemological controversies connected to some of those other definitions. In short, we do believe that ‘simulation’ is an appropriate general term for the method we are presenting here.

So far, we’ve talked about historical simulations as analytical tools for researching history, and this will remain our focus in this lesson. However, simulations can also be didactic tools for interactive and immersive teaching. They are sometimes a synonym for more static 3D reconstructions which are used to visualize past spaces,9 and they can themselves be the subject of research.10

Now that you have a general theoretical idea of historical simulations, we can dive into determining a good methodological approach for our case study. We want to model the interactions of individuals sending letters to each other. Thus, we need a modeling approach that emphasizes those one-on-one interactions: a so-called Agent-Based Model.

1.3 What is Agent-Based Modeling?

Agent-Based Modeling (sometimes ABM for short) is a method which simulates the relations and interactions of individual entities (for example humans, organizations, items, etc.) with each other and with their environment.11

Ideally, these interactions lead to patterns emerging dynamically from the system – meaning they were not prescribed by the researcher. In our case, for example, we actively do not want to prescribe how the letter network should look in the end. We would like to see what shapes naturally arise from the letter-sending rules we set up. If the shape differs wildly from what we observe in our historical data, we know we are probably way off with our hypotheses (or with the way we formalized them).

Agent-Based Models are especially suited to allow for those emergent processes to appear. In general, emergent phenomena in human activity and behavior pose a number of questions that are of central interest for historians and often feature in debates among them, such as:

- ‘How and why did a society change?’

- ‘Why did some states get the upper hand over others in a certain time frame?’

- ‘How did some new technology or idea spread from one group of people to another?’

We must stress that these questions are structural, and are therefore different from questions we might have about specific individuals. In our case, for example, we would not be able to ask ‘Why did Christiaan Huygens send this particular letter to Johannes Hevelius?’, but rather ‘Is there a reason behind the intellectual letter-sending pattern of that era?’

As a simulation method, Agent-Based Modeling offers the opportunity to formally and systematically pursue these kinds of structural questions by building and experimenting with a model of the pertaining case study.

To summarize, the goal of this method is to link the emergent patterns and phenomena at the systemic macro-level with the individual micro-level behavior of interacting entities, the name-giving ‘agents’. The focus is often on the patterns and underlying dynamics of history, rather than any unique case on its own.

1.4 Historical Context of Agent-Based Modeling

The term ‘Agent-Based Modeling’ was introduced during the 1990s, pioneered among others by political scientist Joshua M. Epstein and economist and social scientist Robert Axtell, who used the method to better understand social dynamics.12 Similar individual-based simulation approaches have existed from at least the 1960s, though. Tim Gooding puts the origins of the Agent-Based Modeling approach at 1933, when Enrico Fermi first used the so-called Monte-Carlo Method - a statistical simulation approach - with mechanical computing machines to forecast and analyze results of physical experiments.13

In history, too, simulation approaches comparable to Agent-Based Modeling were adopted rather early and were among the first digital methods applied to historical research. Some of the earlier historical simulation studies were even conducted by pioneering figures of the early digital humanities and digital history, such as Michael Levison, who studied Polynesien voyages in the Pacific in the 1960s and 70s,14 or Peter Laslett from the Cambridge Group for the History of Population and Social Structure, who, together with anthropologist Eugene Hammel and computer scientist Kenneth W. Wachter, devised individual-based Monte-Carlo Simulations on household structures in early modern England. They started in 1971 and publishing a widely reviewed book on the project in 1978.15 Laslett later coined this simulative approach as ‘experimental history’, to underline the experimental and iterative nature of the process.16

Since then, a number of changes occurred that warrant a distinction between those efforts and newer, actual Agent-Based Models. For one, changes in hardware, software and programming paradigms have greatly increased the performance and affordability of bigger, more complex models. Also, the epistemological framework of emergent properties in systems we described in Section 1.2 is heavily inspired by modern thinking on Complex Adaptive Systems.17 This itself has roots into the 1950s and before, but is mainly a product of recent scholarly activity (e.g. in the field of ecology, regarding natural and societal adaptations to climate change18). In newer Agent-Based Modeling, the emphasis is on the principles of relevance of heterogeneous agents, processes of social learning, coupling of micro- and macro-level phenomena and on theory-agnosticism.

Today, Agent-Based Modeling and simulations in general are starting to appear more frequently in historical research, most notably in archaeology (e.g. in simulations of prehistoric settlement patterns19 or in-depth methodological and epistemological discussions20), but also in digital history (e.g. with simulations of different aspects of trade and production in ancient roman economies21) and digital humanities contexts (particularly in recent methodological discussions7) as well.

Part 2: Programming Agent-Based Models with Mesa

In this section, we will start to actually implement a simple simulation model of early modern letter exchange using the Python package mesa. Before we start, we will reiterate our exact goals for this model, which will guide the building process. We then proceed to clarify some key concepts about Agent-Based Models which might be unclear to a beginner.

2.1 Goals

In this lesson, we want to model the networks of letters exchanged between European and American scholars around the 17th century – the ‘Republic of Letters’. For the purposes of this lesson, a very basic model will suffice, but we still want to meet some minimum requirements in order to approach an actual model of the Republic of Letters.

We want:

- A space in which the scholars are situated and can move

- A number of scholars ‘living’ and moving in that space

- The ability for scholars to send each other letters

- The ability for the scholar in front of the screen - that’s you! - to read and interpret the simulation

If you’re worried that this simple list of features will not adequately represent the Republic of Letters, remember that we’re not expecting this lesson to result in building a plausible model. Perhaps it will at least lead to the start of one! We will give you some ideas for extending the model later, to make it more historically plausible.

2.2 What About Data?

You might ask yourself where the actual, empirical data comes into play. One peculiar thing about simulations is that not everything – and sometimes even nothing – is based directly on empirical data. This is because simulations ‘are not trying to model the world […], [they] are trying to model ideas about the world.’22 Each simulation run creates its own data, which then can be analyzed and brought into relation with empirical data.

Thus, empirical data remains an essential element of historical simulations, but it plays a less central role than in network analysis, for example, where the network is entirely based around it.

In historical simulations like ours, we could use empirical data for various purposes. We could use empirical data on individuals of the Republic of Letters to build our agents. We could use surviving empirical data on the historical network to compare with the results of our simulation, in order to see how much they differ. We could (and should) also use extended domain knowledge - be it quantitative data or qualitative scholarship - to inform the properties of our agents, the decisions they can make and the environment they move in.

At this stage of our simple model, we don’t actually need any empirical data yet. For the authors’ own project, which is essentially a more complicated version of this model, we do use a dataset, which you can read more about in the model’s documentation. At the end of the lesson, we will also go into more depth about the methodological implications this has for historical research.

2.3 Key Concepts of Agent-Based Models

Before we finally start coding, you should familiarize yourself with some key concepts of Agent-Based Modeling which will reappear in the rest of this chapter.

Agents

We’ve already mentioned agents - they’re even in the title! An agent is any entity that can ‘act’ in the model: it can move, and alter properties of itself, other agents or its environment. Agents do not have to be humans: according to our very wide conception of ‘acting’ here, animals, plants, organizations or even objects can be agents within the logic of the model.

Space (or Environment)

Space (often used interchangeably with ‘environment’) is the second most important feature of an Agent-Based Model. It is the dimensional space in which Agents can move, which can be understood literally or very abstractly - for example, in a different model we built at ModelSEN, the space agents ‘move’ in is a representation of the knowledge they hold. This space may also be filled with static elements of the model (such as climate, natural features, or relevant abstract elements).

Model

The model is the combination of the agents and their environment, as well as their interactions and any further logic that ties everything together. The model is really only complete when it is running, which is when all the interactions are computed.

Time

In order to be able to compute interactions as a sequence of steps, models require a concept of time. There are different ways to model the passage of time in an Agent-Based Model: it could use discrete time steps (like turns in a game), or a more continuous flow of time.

Experimentation

The temporal nature of simulation models also means that you will have to constantly run, tweak and rerun your model. This practice of iterative experimentation is not just a practical necessity, though, but a virtue of the method, because your knowledge of the system’s dynamics, specifically what can or cannot work within the bounds of your assumptions, will grow over time. One important implication of this constant improvement is that any simulation model provides at most an imperfect perspective on history.

2.4 Overview of Mesa

In this tutorial, we will use mesa, an open-source Agent-Based Modeling framework written in Python. Mesa offers predefined functions to implement the key ingredients of an Agent-Based Model. The package has been in development since 2015 and has acquired a large community of users and contributors (see the mesa Github repository). Its relative longevity and popularity makes it a good choice to begin with Agent-Based Modeling.

If you are more familiar with other programming languages, you can consider applying this tutorial to other frameworks, like NetLogo (a dedicated Agent-Based Modeling language) or MASON (based on Java).

In mesa, a minimal Agent-Based Modeling implementation consists of defining an ‘agent’ class and a ‘model’ class. The model class holds the model-level attributes (for example, attributes of the environment or other external factors), manages the agents, and generally handles the global processing level of our model.

Each instantiation of the model class will be a specific model we run. Each model will contain multiple agents, all of which are instantiations of the agent class. We assign a unique ID to each agent to be able to track them during the simulation. Both the model and agent classes are child classes of mesa’s generic Model and Agent classes.

Another important aspect of mesa is its ‘scheduler’, which keeps track of when each agent should act. Mesa calls this process ‘activation’, and there are several types of predefined activation procedures: random, simultaneous, or staged. In this tutorial, we will use random activation, which means that all agents will act one after the other, in an order that is randomly reassigned at every step of the model.

Some research questions might require the agents to interact in or with a space, which could either be a geographical space or something more abstract. Sometimes, like in this lesson, a simple abstract representation of relative distance is sufficient, for example in the form of a two-dimensional grid. Mesa also supports hexagonal, continuous or network grids, which are useful for covering geographical space or simulating social relations. If a simulation relies on geographical map projections, the additional mesa-geo package from the mesa project might be useful.

2.5 Building the Model

We are now ready to start with the actual modeling. We’ll first introduce the agents, then the model, and finally the agents’ activation. Let’s get started!

"""To start with, let's import the mesa module"""

import mesa

2.5.1 Setting up the model

To begin writing the model code, we start with two core classes: one for the agents, the other for the overall model. Let’s start with the new agent class: class LetterAgent(mesa.Agent).

For now, each agent only has two variables: the number of letters it has currently sent, and the number of letters it has received. Each agent will also have a unique identifier (i.e. a name), stored in the unique_id variable. Giving each agent a unique ID is good practice when doing Agent-Based Modeling.

class LetterAgent(mesa.Agent):

"""An agent with unique_id but no initial letters."""

def __init__(self, unique_id, model):

super().__init__(unique_id, model)

self.letters_sent = 0

self.letters_received = 0

Next, we need a model: class LetterModel(mesa.Model). There is only one model-level parameter: the number of agents it contains. When a new model is started, we want it to populate itself with the given amount of agents.

class LetterModel(mesa.Model):

"""A model with N agents."""

def __init__(self, N):

super().__init__()

self.num_agents = N

# Create N agents

for i in range(self.num_agents):

a = LetterAgent(i, self)

2.5.2 Adding Time

In most Agent-Based Models, time moves in steps, sometimes called ‘ticks’. At each step of the model, one or more of the agents – usually all of them – are activated and take their own step. This step could involve changing internally and/or interacting with one another or their environment.

The scheduler is a special model component which controls the order in which agents are activated. For example, all the agents may activate in the same order at every step, their order might be shuffled, we may try to simulate all the agents acting simultaneously, etc. Mesa offers a few different built-in scheduler classes, with a common interface. That makes it easy to change the activation regime a given model uses, and see whether it changes the model behavior. This may not seem important, but scheduling patterns can have a big impact on your results. The severity of those impacts, depending on the type of activation chosen, is still a topic of research and debate – still, potential effects on your model should be considered and be made clear.23

For now, let’s use one of the simplest ones: RandomActivation24, which activates all the agents once per step, in a random order.

self.schedule = mesa.time.RandomActivation(self)

Every agent is expected to have a ‘step method’. This is the action it takes when it is activated by the model scheduler. We add an agent to the schedule using the add method; when we call the schedule’s step method self.schedule.step(), the model shuffles the order of the agents, then activates and executes each agent’s step.

def step(self):

# The agent's step will go here.

# For demonstration purposes we will print the agent's unique_id

print("Hi, I am agent " + str(self.unique_id) + ".")

Let’s add all these parts together:

class LetterAgent(mesa.Agent):

"""An agent with unqiue_id but no initial letters."""

def __init__(self, unique_id, model):

super().__init__(unique_id, model)

self.letters_sent = 0

self.letters_received = 0

def step(self):

# The agent's step will go here.

# For demonstration purposes we will print the agent's unique_id

print("Hi, I am agent " + str(self.unique_id) + ".")

class LetterModel(mesa.Model):

"""A model with N agents."""

def __init__(self, N):

super().__init__()

self.num_agents = N

self.schedule = mesa.time.RandomActivation(self)

# Create N number of agents

for i in range(self.num_agents):

a = LetterAgent(i, self)

self.schedule.add(a)

def step(self):

"""Advance the model by one step."""

self.schedule.step()

At this point, we have a model which runs – it just doesn’t do anything in terms of letter sending or receiving. You can see for yourself with a few easy lines:

empty_model = LetterModel(10) # create a model with 10 agents

empty_model.step() # execute the step function once

Figure 1. Currently, the only thing our agents do is say ‘Hi!’

Bonus Question 1: Try changing the scheduler from

RandomActivationtoBaseScheduler. What do you observe at the agent’s output? How would you need to define your agents if you would like to use StagedActivation?

Hint: Take a look at the source code ofmesa.time!

2.5.3 Agent Step

Now, we just need to make the agents do what we intend them to do: send each other letters.

To allow each agent to choose another agent at random, we use the model.random random number generator. This works just like Python’s random module, but with a fixed seed set when the model is instantiated. You can use it to replicate a specific model run later.

To pick an agent at random, we need a list of all agents. Notice that such a list doesn’t explicitly exist in the model. However, the scheduler does have an internal list of all the agents it is scheduled to activate.

With that in mind, we rewrite the agent step method like this:

class LetterAgent(mesa.Agent):

"""An agent with no initial letters."""

def __init__(self, unique_id, model):

super().__init__(unique_id, model)

self.letters_sent = 0

self.letters_received = 0

def step(self):

other_agent = self.random.choice(self.model.schedule.agents)

other_agent.letters_received += 1

self.letters_sent += 1

2.5.4 Running your First Model

With that last piece in hand, it’s time for the first rudimentary run of the model. Let’s create a model with 10 agents, and run it for 20 steps.

model = LetterModel(10)

for i in range(20):

model.step()

Next, we need to get some data out of the model. Specifically, we want to see how many letters each agent sent or received. We can get these values with list comprehension, and then use matplotlib (or another graphics library) to visualize the data in a histogram.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

agent_letters_recd = [b.letters_received for b in model.schedule.agents]

plt.hist(agent_letters_recd, bins=range(10,30))

plt.xticks(range(10,31))

plt.xlabel("Letters Received")

plt.ylabel("Number of Agents")

plt.show()

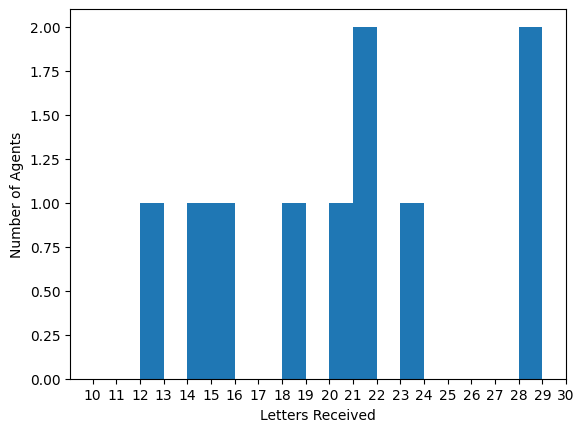

Figure 2. Histogram of the letters received by all agents.

You should get something like the distribution above. Yours will almost certainly be slightly different, since each run of the model is random and unique.

To get a better idea of how a model behaves, we can create multiple model runs and observe the distribution that emerges. We can do this with a nested for loop:

all_letters_rec = []

# This runs the model with 10 agents 100 times, each model executing 10 steps.

for j in range(100):

# Run the model

model = LetterModel(10)

for i in range(10):

model.step()

# Store the results

for agent in model.schedule.agents:

all_letters_rec.append(agent.letters_received)

plt.hist(all_letters_rec, bins=range(max(all_letters_rec) + 1))

plt.xticks(range(max(all_letters_rec) + 1))

plt.xlabel("Letters Received")

plt.ylabel("Number of Agents")

plt.show()

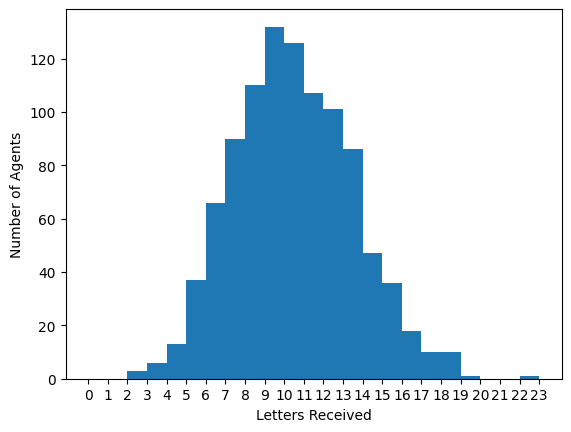

Figure 3. Histogram of the letters received by all agents after 100 model runs.

This runs 100 instantiations of the model, each of which runs for 10 steps. (Notice that we set the histogram bins to integers, since agents can only receive whole numbers of letters.) By running the model 100 times, we smooth out some of the ‘noise’ of randomness, and approach the model’s overall expected behavior. For now, the letter distribution looks close to a normal distribution (or bell curve), which is expected since the process is random.

Bonus question 2:

Can you rewrite the last code block to plot the number of sent letters instead? What histogram do you expect for that?

Hint: Are agents sending letters in every round?

2.5.5 Adding Space

Let’s add some more realistic behavior by introducing space between the agents, which should influence their letter-sending decisions. Mesa currently supports two kinds of spaces: ‘grid’ and ‘continuous’. Grids are divided into cells, and agents exist on one particular cell, like pieces on a chess board. Continuous space, in contrast, allows agents to take any arbitrary position. Both grids and continuous spaces are frequently toroidal, meaning that the edges of this ‘world’ wrap around, with cells on the right edge connected to those on the left edge, and the top to the bottom. This prevents some cells from having fewer neighbors than others, or agents being able to fall off the edge of the environment.

Let’s add a simple spatial element to our model by putting our agents on a grid, and making them move around it at random. Instead of sending a letter to any random agent, they’ll give it to an agent on the same cell. We could imagine that this represents them existing close enough to know each other and have reasons to send a letter in the first place.

Mesa offers two main types of grids: SingleGrid and MultiGrid.25 SingleGrid enforces at most one agent per cell; MultiGrid allows multiple agents in the same cell. Since we want agents to be able to share a cell, we use MultiGrid, which we instatiate with width and height paramaters, and which will always be toroidal (hence the True designation):

self.grid = mesa.space.MultiGrid(width, height, True)

We can place agents on the grid with the place_agent method, which automaticelly assigns an (x, y) tuple of grid coordinates to each agent a.

self.grid.place_agent(a, (x, y))

Add all the pieces together like this:

class LetterModel(mesa.Model):

"""A model with a certain number of agents."""

def __init__(self, N, width, height):

super().__init__()

self.num_agents = N

self.grid = mesa.space.MultiGrid(width, height, True)

self.schedule = mesa.time.RandomActivation(self)

# Create agents

for i in range(self.num_agents):

a = LetterAgent(i, self)

self.schedule.add(a)

# Add the agent to a random grid cell

x = self.random.randrange(self.grid.width)

y = self.random.randrange(self.grid.height)

self.grid.place_agent(a, (x, y))

Now, we need to add the agents’ behaviors: we’ll let them move around and send letters to agents in the same cell as them.

First, let’s handle movement: we want the agents to move to a neighboring cell. The grid object provides a move_agent method which, as you can imagine, moves an agent to a given cell. We still need to limit this movement to neighboring cells only. There are a couple ways to do this. One is to use the current coordinates, and loop over all coordinates +/- 1 away from it. For example:

neighbors = []

x, y = self.pos

for dx in [-1, 0, 1]:

for dy in [-1, 0, 1]:

neighbors.append((x+dx, y+dy))

An even simpler way of doing this is using the grid’s built-in get_neighborhood method, which returns all the neighbors of a given cell. This method can get two types of cell neighborhoods: Von Neumann (only includes the 4 top, bottom, left and right neighboring squares) and Moore (includes all 8 surrounding squares). get_neighborhood also lets you decide whether to include the center cell itself as one of its ‘neighbors’.

With that in mind, here is our agent’s move method:

class LetterAgent(mesa.Agent):

#...

def move(self):

possible_steps = self.model.grid.get_neighborhood(

self.pos,

moore=True,

include_center=False)

new_position = self.random.choice(possible_steps)

self.model.grid.move_agent(self, new_position)

Next, we need to find all the other agents present in our agent’s new cell, and send one of them a letter. We can get the contents of one or more cells using the grid’s get_cell_list_contents method. The method accepts either a single coordinate tuple, or a list of tuples.

class LetterAgent(mesa.Agent):

#...

def send_letter(self):

cellmates = [a for a in self.model.grid.get_cell_list_contents([self.pos]) if a != self]

if len(cellmates) > 1:

other = self.random.choice(cellmates)

other.letters_received += 1

self.letters_sent += 1

And with those two methods, the agent’s step method becomes:

class LetterAgent(mesa.Agent):

# ...

def step(self):

self.move()

self.send_letter()

Now, put that all together:

class LetterAgent(mesa.Agent):

"""An agent with letters sent and received.

The agent can move to agents in other grid cells

and send letters to agents in the same grid cell.

"""

def __init__(self, unique_id, model):

super().__init__(unique_id, model)

self.letters_sent = 0

self.letters_received = 0

def move(self):

possible_steps = self.model.grid.get_neighborhood(

self.pos, moore=True, include_center=False

)

new_position = self.random.choice(possible_steps)

self.model.grid.move_agent(self, new_position)

def send_letter(self):

cellmates = [a for a in self.model.grid.get_cell_list_contents([self.pos]) if a != self]

if len(cellmates) > 1:

other_agent = self.random.choice(cellmates)

other_agent.letters_received += 1

self.letters_sent += 1

def step(self):

self.move()

self.send_letter()

Let’s create a model with 50 agents on a 10x10 grid, and run it for 20 steps.

model = LetterModel(50, 10, 10)

for i in range(20):

model.step()

Now let’s use matplotlib and numpy to visualize the number of agents residing in each cell after 20 steps. To do that, we create a numpy array of the same size as the grid, filled with zeros. Then, we use the grid object’s coord_iter() feature, which lets us loop over every cell in the grid, giving us each cell’s coordinates and contents in turn.

import numpy as np

agent_counts = np.zeros((model.grid.width, model.grid.height))

for cell in model.grid.coord_iter():

cell_content, coord = cell

x, y = coord

agent_count = len(cell_content)

agent_counts[x][y] = agent_count

plt.imshow(agent_counts, interpolation="nearest")

plt.colorbar(label="Number of Agents present in Cell")

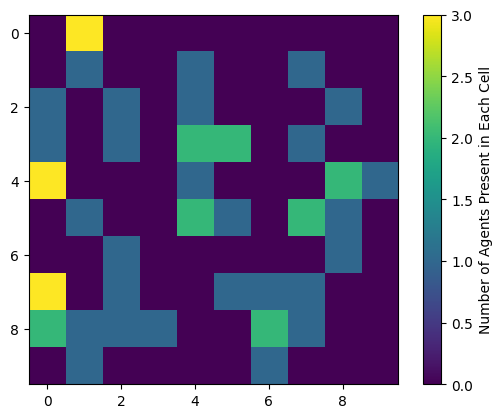

Figure 4. Color mesh showing the number of agents present on each cell of our grid space.

Bonus question 3:

Letters are currently sent to agents in the same cell, representing direct neighbors. How could you implement sending letters only to agents who ‘live’ further away, e.g. with at least a distance of three cells?

Hint: You will have to define a distance measure on grids. See for example this Programming Historian lesson on similarity measures.

2.5.6 Collecting Data

So far, at the end of every model run, we’ve had to write our own code to retrieve the data from the model. This has two problems: it isn’t very efficient, and it only provides end results. If we wanted to know the number of letters each agent has sent and received at every step, we’d have to add this in to the loop of executing steps, and find a way to store that data.

Since one of the main goals of Agent-Based Modeling is generating data for analysis, mesa provides a class which can handle data collection and storage. This ‘data collector’ stores three categories of data: model-level variables, agent-level variables, and tables (which is a catch-all term for everything else). Model- and agent-level variables are added to the data collector along with a function for collecting them. Model-level collection functions take a model object as an input, while agent-level collection functions take an agent object as an input.

When the data collector’s collect method is called with a model object as its argument, it applies each model-level collection function to the model, and stores the results in a dictionary, linking the value to the current step of the model. If the input model is an agent, the method also links the resulting value to the agent’s unique_id.

Let’s add a data collector to the model with mesa.DataCollector, and collect two variables at the agent level: the number of letters every agent has sent at every step, and the number of letters it has received.

self.datacollector = mesa.DataCollector(

agent_reporters={

"Letters_sent": "letters_sent",

"Letters_received": "letters_received"

},

model_reporters={

"All letters":compute_received_letters

}

)

Additionally, we define a new function to collect data at the model level. This function just collects the total number of letters received by all agents.

def compute_received_letters(model):

number_of_received_letters = 0

for agent in model.schedule.agents:

number_of_received_letters += agent.letters_received

return number_of_received_letters

By defining this function in our script and then updating the LetterModel in the following way, we can finally collect data:

class LetterModel(mesa.Model):

"""A model with a certain number of agents."""

def __init__(self, N, width, height):

super().__init__()

self.num_agents = N

self.grid = mesa.space.MultiGrid(width, height, True)

self.schedule = mesa.time.RandomActivation(self)

# Create agents

for i in range(self.num_agents):

a = LetterAgent(i, self)

self.schedule.add(a)

# Add the agent to a random grid cell

x = self.random.randrange(self.grid.width)

y = self.random.randrange(self.grid.height)

self.grid.place_agent(a, (x, y))

self.datacollector = mesa.DataCollector(

agent_reporters={

"Letters_sent": "letters_sent",

"Letters_received": "letters_received"

},

model_reporters={"All letters":compute_received_letters}

)

def step(self):

self.schedule.step()

self.datacollector.collect(self)

After every step of the model, the data collector will collect and store each agent’s letters_sent and letters_received values.

We run the model just as we did above:

model = LetterModel(50, 10, 10)

for i in range(100):

model.step()

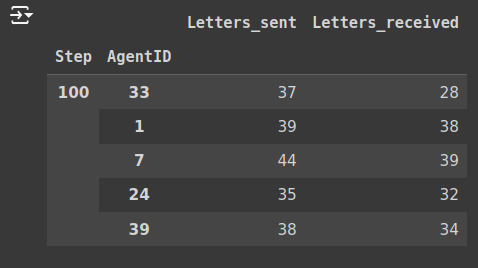

The DataCollector can export the data it has collected as a pandas DataFrame, allowing for easy interactive analysis. We can get the agent_letters data (the combined agent-level and model-level data) like this:

agent_letters = model.datacollector.get_agent_vars_dataframe()

agent_letters.tail()

Figure 5. Number of letters sent and received by a selection of agents, at step 100 of the simulation.

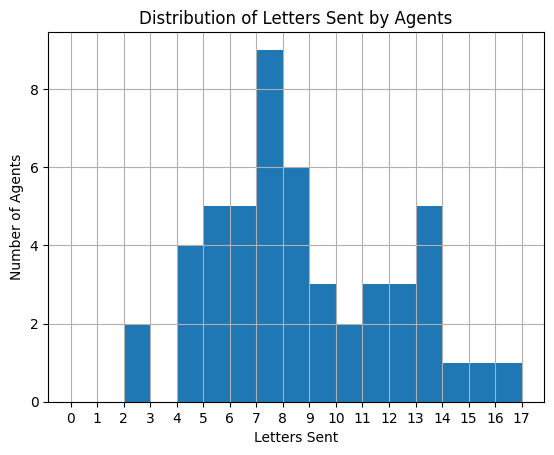

You’ll see that the DataFrame’s index consists of pairings of model step and agent ID. You can analyze it the way you would any other DataFrame, by following the Programming Historian lesson on Visualizing Data with Bokeh and Pandas, for example. Let’s get a histogram of the total numbers of letters sent by agents at the model’s end:

end_letters = agent_letters.xs(99, level="Step")["Letters_sent"]

bin_range = range(agent_letters.Letters_sent.max() + 1)

end_letters.hist(bins=bin_range)

plt.xticks(bin_range)

plt.xlabel("Letters Sent")

plt.ylabel("Number of Agents")

plt.title("Distribution of Letters Sent by Agents")

plt.show()

Figure 6. Histogram of letters sent by agents after 100 steps of simulating the model.

You can also use pandas to export the data to a CSV (comma-separated value) file, which can be opened by any common spreadsheet application.

If you do not specify a file path, the file will be saved in the local directory. After you run the code below, you will see the file agent_data.csv appear.

agent_letters.to_csv("agent_data.csv")

Having exported the data, we can now follow several approaches to test the hypotheses that we initially encoded in the model. The goal to systematically test - or validate - a model is to check if the model actually represents what it is supposed to. This can range from simply comparing your expectations with the outputs, to systematically analyzing the internal consistency of the model. Calibrating your model to available empirical data is one of the most simple and robust methods of testing, but of course this might be challenging due to data availability. A more involved method is to explore in detail the effects of a wide range of possible simulation parameters (a so-called ‘parameter space’). Mehdizadeh et al 2022, p. 8-9, writing from the perspective of mobility studies, offer a sensible differentiation of various validation methods, as well as good examples of how to evaluate Agent-Based Models in other fields.26

In our case, we’re interested in whether changing the model parameters leads to results that correspond to our expectations. For example, if we were to use a different random distribution to guide the letter sending, we would expect to see a different distribution of letters received.

Another option lies in the concept of Network Morphospaces,27 which is a type of parameter space analysis. With this approach, we would run the model several times for every possible parameter and record the resulting outputs. Possible parameter examples include the likelihood of agents sending a letter at each step, the range of possible neighbors, or the effect of the letters’ content. Alongside measuring the resulting output (e.g. fitting it to a distribution, or in the case of network output, its centralities), these parameter sets yield a ‘fingerprint’ of each unique simulation run, which can be used to create an abstract ‘embedding space’. You can read about this space in the Programming Historian lesson on word embeddings.

By including empirical data into such a space – in our case, networks taken from historical sources – we can observe which parameter sets bring the simulated outcome closest to the observed outcome. By adapting both the way in which hypotheses are encoded in the model, and the simulation parameters chosen, we can bring the model outcome closer to empirical findings and therefore determine the hypotheses which best explain the real-world processes that shaped the historical network.

Bonus question 4: Try to plot the time series of letters recieved by a single agent. Hint: You can access the dataframe in the same way, this time on the level of the AgentID. Instead of using

dataframe.hist(), usedataframe.plot().

Bonus question 5: So far, we have collected only counts of letters sent and received. How could we capture the sending of a letter as a link between sender and receiver? Can you create a model reporter that writes this information into a letter ledger?

Hint: The information should be stored in a model variable, which is appended to every agent’s letter sending step. You can have a look at the published Historical Letters model 1.1.0.

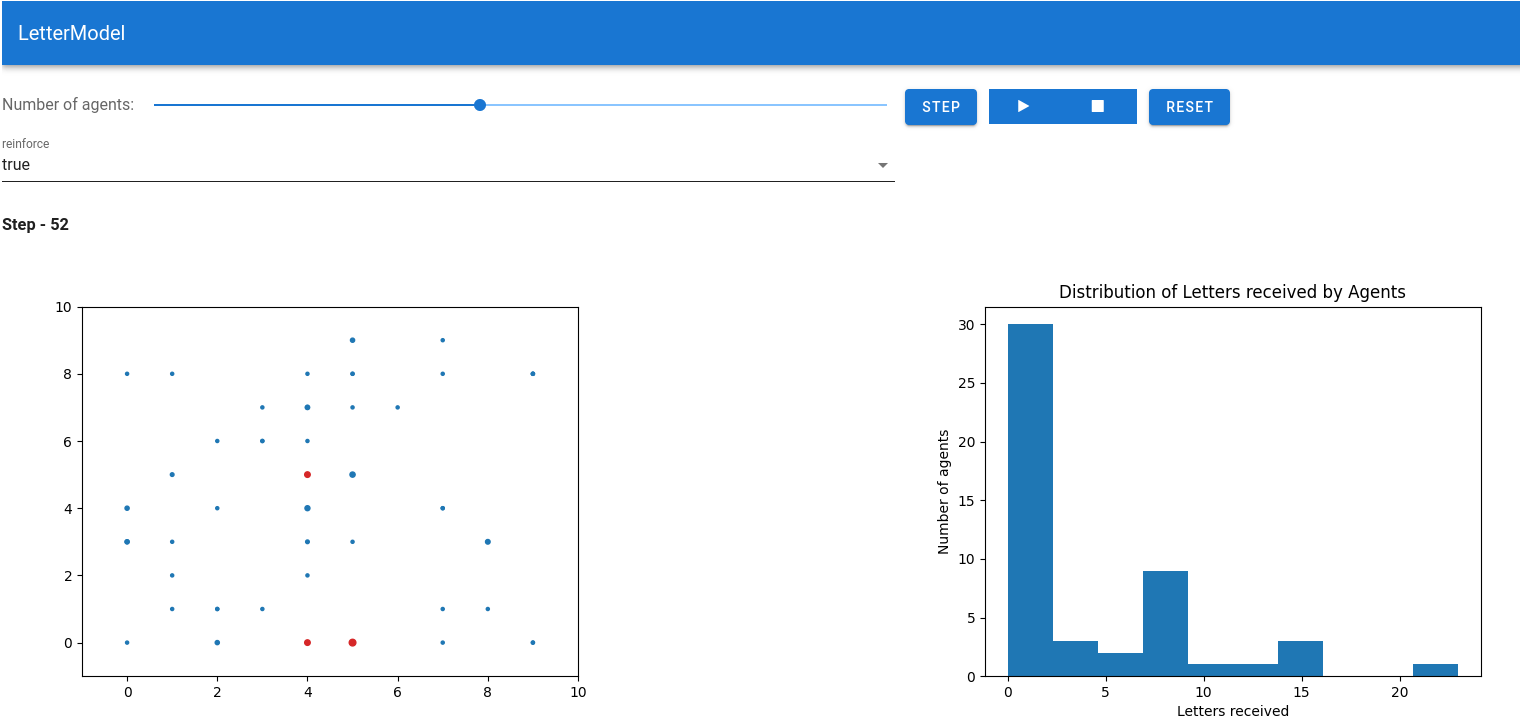

2.5.7 Visualization and Interactive Features of Mesa

Recently, the mesa contributors introduced the possibility to control and visualize a simulation directly from within a Jupyter Notebook.

To create a visualization, we need to define three components: the portrayal of the agents in the visualization, the parameters we want to control, and finally the visualization itself. The portrayal includes the agent’s color and size: to introduce some visual cues to the model, we change the agents’ color once they have received a certain number of letters.

def agent_portrayal(agent):

color = "tab:blue"

size = 5

agents_letters = agent.letters_received

if agents_letters > 5:

size = agents_letters

if agents_letters > 15:

color = "tab:red"

return {

"color": color, "size": size,

}

We want to be able to control the number of agents that are generated. This is an integer number, which we allow to be changed from 10 to 100 agents, in increments of one. The width and height of the grid will stay fixed throughout the simulation.

Additionally, we introduce the option to switch between two ways in which agents select a neighbor to whom to send their letter. While both methods involve randomly selecting an agent from a list, when reinforce is set to True, the selection is weighted by the neighbors’ number of letters received. This means that agents who have already received letters are more likely to keep receiving even more. In this way, we can allow agents to become, in a sense, more ‘famous’. This is one simple possible mechanism for modeling why well-known people like Christiaan Huygens received many more letters than other members of the Republic of Letters.

To initialize the agents with this new option, we’ll also add a model parameter which allows us to switch the reinforce parameter on (True) or off (False).

if self.reinforce == False:

other_agent = self.random.choice(cellmates)

else:

weights = [x.letters_received for x in cellmates]

if sum(weights) == 0:

weights = None

other_agent = self.random.choices(

population=cellmates,

weights=weights,

k=1

)[0]

We’ll also reduce the rate of agents moving to different cell at every step, as people don’t constantly relocate. For this, we introduce another weighted random choice, this time with fixed weight. Now, the chance of an agent moving will only be 20%, or whenever they draw a ‘1’.

if self.random.choices([0,1], weights=[0.8, 0.2], k=1)[0] == 1:

new_position = self.random.choice(possible_steps)

self.model.grid.move_agent(self, new_position)

All together, we get the following new definitions for agents and model:

class LetterAgent(mesa.Agent):

"""An agent with letters sent and letters received."""

def __init__(self, unique_id, model, reinforce=False):

super().__init__(unique_id, model)

self.letters_sent = 0

self.letters_received = 0

self.reinforce = reinforce

def move(self):

possible_steps = self.model.grid.get_neighborhood(

self.pos, moore=True, include_center=False

)

if self.random.choices([0,1], weights=[0.8, 0.2], k=1)[0] == 1:

new_position = self.random.choice(possible_steps)

self.model.grid.move_agent(self, new_position)

def send_letter(self):

cellmates = [a for a in self.model.grid.get_cell_list_contents([self.pos]) if a != self]

if len(cellmates) > 1:

if self.reinforce == False:

other_agent = self.random.choice(cellmates)

else:

weights = [x.letters_received for x in cellmates]

if sum(weights) == 0:

weights = None

other_agent = self.random.choices(

population=cellmates,

weights=weights,

k=1

)[0]

other_agent.letters_received += 1

self.letters_sent += 1

def step(self):

self.move()

self.send_letter()

class LetterModel(mesa.Model):

"""A model with a certain number of agents."""

def __init__(self, N, width, height, reinforce=False):

super().__init__()

self.num_agents = N

self.grid = mesa.space.MultiGrid(width, height, True)

self.schedule = mesa.time.RandomActivation(self)

# Create agents

for i in range(self.num_agents):

a = LetterAgent(i, self, reinforce)

self.schedule.add(a)

# Add the agent to a random grid cell

x = self.random.randrange(self.grid.width)

y = self.random.randrange(self.grid.height)

self.grid.place_agent(a, (x, y))

self.datacollector = mesa.DataCollector(

agent_reporters={"Letters_sent": "letters_sent", "Letters_received": "letters_received"},

model_reporters={ "Letters_received": compute_received_letters}

)

def step(self):

self.schedule.step()

self.datacollector.collect(self)

We can now set up the interface for parameters we want to control in the visualization:

model_params = {

"N": {

"type": "SliderInt",

"value": 50,

"label": "Amount of agents:",

"min": 10,

"max": 100,

"step": 1,

},

"reinforce": {

"type":"Select",

"value": False,

"values": [True, False]

},

"width": 10,

"height": 10,

}

The model can be visualized using the (currently experimental) Solara package. This package also lets us define our own visualizations, for example with a histogram.

import solara

from matplotlib.figure import Figure

def make_histogram(model):

fig = Figure()

ax = fig.subplots()

letter_vals = [agent.letters_received for agent in model.schedule.agents]

ax.hist(letter_vals, bins=10)

ax.set(

xlabel="Letters received",

ylabel="Number of agents",

title="Distribution of Letters received by Agents"

)

solara.FigureMatplotlib(fig, format="png")

By defining the agent_protrayal settings, the model parameters, and the histogram function, together with the main Letter Model, we can now call the simulation and let the model run for a while. Do you see the agents’ colors change?

from mesa.experimental import JupyterViz

simulation = JupyterViz(

LetterModel,

model_params,

measures=[make_histogram],

name="LetterModel",

agent_portrayal=agent_portrayal,

)

simulation

Figure 7. Interactive interface for the simulation with multiple real-time visualizations.

What difference do you observe in the visualization when switching between reinforce True or False?

Bonus question 6: How could you use reinforcement for the movement process? You could make ‘famous’ senders more likely to be the target of a movement process.

Part 3: Summary, Open Questions and Next Steps

Now, we have a relatively basic model to depict the exchange of letters during the time of the Republic of Letters. Our model has the following features:

- A grid-like space, the cells of which are occupied by agents

- Agents can send each other letters

- Agents can move about in space

It also has these bonus features:

- Agents can send letters to others more than one cell away

- A letter ledger, akin to an edge-list of a network

- Agents can move purposefully in the direction of more ‘famous’ agents, i.e. those who receive many letters

Of course, this model is still quite a distance away from being a plausible model of the Republic of Letters, but it has some of the most important base features.

The question remains: how could you keep improving this model – and how could you keep working with Agent-Based Modeling in general?

3.1 Suggestions for Extending the Model

You may have your own ideas for extending the model, but we want to provide some inspiration for further improvements. Importantly, we want to suggest to you some features that are strongly connected to the historical subject matter, and which raise some interesting modeling challenges:

- Implement a way for agents to ‘die’ and new agents to be ‘born’ during the simulation. In the real world, not only did some letter writers actually die at some point, but they also might have gone through phases of higher or lower letter-writing intensity.

- Consider how you might represent the knowledge that is exchanged, and how this should influence the other parts of the model. In the end, one of the most interesting aspects about the Republic of Letters is that it likely had a transformative impact on scientific activity in Europe. Try to envisage how this aspect could be analyzed with this model.

- Implement an actual geographic space, rather than a grid. Space has important repercussions on movement and letter-sending dynamics. Also, the Republic of Letters mainly featured people in the Low Countries and Northern Italy. Think about which geographical aspects of the Republic of Letters should be present in the model, and how to implement them. To do this, maybe take a look at mesa-geo, a GIS (Geoinformation System) extension of the mesa package.

For more inspiration, you might also want to look at the authors’ own extended version of this model!

3.2 Further Steps and Resources

There is a lot more to learn, not only on the technical side of things, but also about the unique quirks and best practices of Agent-Based Modeling.

For any technical questions, we suggest you head over to mesa’s documentation, which also features tutorials on advanced features, especially built-in javascript-based visualization methods. You can also head to YouTube for these comprehensive video tutorials.

We also want to touch on a key methodological aspect we cannot fully cover here, which is documenting and publishing Agent-Based Models. There exists a developing – but already well established – method of formally documenting these complex beasts: ‘Overview, Design Concepts, Details’ (ODD).28 An ODD is a document in which you describe all your model’s features and design intentions, with the explicit aim that this information should be sufficent for others to replicate a version of your model. Writing an ODD can also help you better understand your own goals, as well as discover possible gaps in your model, too!

Many models are published on the CoMSES website, hosted by the Network for Computational Modeling in Social and Ecological Sciences. We recommend you browse through their model library, as well as publish your own model’s code and ODD there. While it is not a platform geared towards historians (such a platform sadly does not exist yet), it is a great space that encourages reproducibility, reusability and even provides the opportunity for peer review, if desired. Many models are published in early, unfinished states to gather feedback. Models are often developed collaboratively in this way, and you should not hesitate to publish preliminary work in a venue such as this. This strong tradition of collaborative, experimentative and iterative work can be a great asset to your own modeling.

3.3 Final Remarks

Agent-Based Modeling for historians is still in its early phase, but there is a growing number of people who apply simulation methods to historical research questions. There are many open questions left regarding the method’s implications and prerequisites for historical inquiry!

Methodological criticism, which is so important for today’s digital history, is still just unfolding for ABM, but this also leaves much room for exciting discussion and discoveries.

Do not hesitate to get in touch with us if you want to be part of this discussion and if you want to help us build a community of practice around historical simulation methods!

Endnotes

-

Hotson, Howard, and Thomas Wallnig, [Eds.] (2019), Reassembling the Republic of Letters in the Digital Age: Standards, Systems, Scholarship. Göttingen, Germany: Göttingen University Press. https://doi.org/10.17875/gup2019-1146. ↩

-

Ureña-Carrion, Javier, Petri Leskinen, Jouni Tuominen, Charles van den Heuvel, Eero Hyvönen, and Mikko Kivelä (2021), Communication Now and Then: Analyzing the Republic of Letters as a Communication Network. http://arxiv.org/abs/2112.04336. ↩

-

Miert, Dirk van (2014), “What was the Republic of Letters? A brief introduction to a long history.” Groniek, no. 204/5 (2014). https://ugp.rug.nl/groniek/article/view/27601. ↩

-

Schmitz, Jascha Merijn: Simulation. In: AG Digital Humanities Theorie des Verbandes Digital Humanities im deutschsprachigen Raum e. V. (Hg.): Begriffe der Digital Humanities. Ein diskursives Glossar (= Zeitschrift für digitale Geisteswissenschaften / Working Papers, 2). Wolfenbüttel 2023. 25.05.2023. Version 2.0 vom 16.05.2024. HTML / XML / PDF. https://doi.org/10.17175/wp_2023_011_v2. ↩

-

Gavin, Michael. Agent-Based Modeling and Historical Simulation. Digital Humanities Quarterly, 008(4):195, December 2014. http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/8/4/000195/000195.html. ↩

-

Romein, C. A., Max Kemman, Julie M. Birkholz, J. Baker, M. D. Gruijter, Albert Meroño-Peñuela, T. Ries, Ruben Ros, S. Scagliola (2020). State of the Field: Digital History. In: Journal of the Historical Association 105 (365), pp. 291-312. ↩

-

McCarty, Willard (2019). “Modeling the Actual, Simulating the Possible.” In The Shape of Data in the Digital Humanities: Modeling Texts and Text-Based Resources / Edited by Julia Flanders and Fotis Jannidis, and Willard McCarty. London: Routledge. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9781315552941. ↩ ↩2

-

Scheuermann, Leif (2022), Über die Rolle computerbasierter Modellrechnungen und Simulationen für eine digitale Geschichte, In Digital History. Konzepte, Methoden und Kritiken Digitaler Geschichtswissenschaft. edited by Karoline Dominika Döring, Stefan Haas, Mareike König, and Jörg Wettlaufer. Berlin; Boston 2022 (Studies in Digital History and Hermeneutics 6). ↩

-

Wendell, Augustus, Burcak Ozludil Altin, and Ulysee Thompson (2016), “Prototyping a Temporospatial Simulation Framework:Case of an Ottoman Insane Asylum,” 485–91. Oulu, Finland. https://doi.org/10.52842/conf.ecaade.2016.2.485. ↩

-

Winsberg, Eric (2019), “Computer Simulations in Science.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, eds.: Edward N. Zalta. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2019/entries/simulations-science/. ↩

-

Schmitz, Jascha Merijn and Buarque, Bernardo Sousa. 2023. “Introduction to Agent-Based Modeling for Historians”, ModelSEN Compendium. https://modelsen.gea.mpg.de/jupyterbooks/book/abmintro/. Accessed: June 3rd, 2024. ↩

-

Epstein, Joshua M., and Robert Axtell (1996), Growing Artificial Societies. Social Science from the Bottom Up. Washington: Brookings Institution Press. ↩

-

Gooding, Tim (2019), “Agent-Based Model History and Development.” In Economics for a Fairer Society, by Tim Gooding, 25–36. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-17020-2_4. ↩

-

Levison, M, R Gerard Ward, and John W Webb,(1972), “The Settlement of Polynesia: A Report on a Computer Simulation.” Archaeology & Physical Anthropology in Oceania 7, no. 3 (1972): 234–45. ↩

-

Wachter, Kenneth W., Peter Laslett, and Eugene A. Hammel (1978), Statistical Studies of Historical Social Structure. Population and Social Structure: Advances in Historical Demography. London: Academic Press. ↩

-

Wachter, Kenneth W., and Eugene A. Hammel (1986), “The Genesis of Experimental History.” In The World We Have Gained: Histories of Population and Social Structure. Essays Presented to Peter Laslett on His Seventieth Birthday., edited by Lloyd Bonfield, Richard M. Smith, and Keith Wrightson. Oxford: Basil Blackwell Ltd. ↩

-

Mitchell, Melanie (2011), Complexity: A Guided Tour. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ↩

-

See for example Alexander, Sarah and Paul Block (2022), Integration of seasonal precipitation forecast information into local-level agricultural decision-making using an Agent-Based Model to support community adaptation, in: Climate Risk Management 36, p.100417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2022.100417. ↩

-

Sikk, Kaarel and Geoffrey Caruso (2020), A spatially explicit Agent-Based Model of central place foraging theory and its explanatory power for hunter-gatherers settlement patterns formation processes, in: Adaptive Behavior 28 (5), pp. 377-397. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059712320922915. ↩

-

Graham, Shawn. An Enchantment of Digital Archaeology: Raising the Dead with Agent-Based Models, Archaeogaming and Artificial Intelligence. Digital Archaeology: Documenting the Anthropocene 1. online: Berghahn Books, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781789207873. ↩

-

Brughmans, Tom, and Andrew Wilson, eds. Simulating Roman Economies: Theories, Methods, and Computational Models. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780192857828.001.0001. ↩

-

Wachter, Laslett and Hammel 1978, p. xix ↩

-

Comer, Kenneth W. “Who Goes First? An Examination of the Impact of Activation on Outcome Behavior in AgentBased Models.” George Mason University, 2014. https://hdl.handle.net/1920/9070. ↩

-

Unlike

mesa.modelormesa.agent,mesa.timehas multiple classes (e.g.RandomActivation,StagedActivationetc). To ensure context, time is used in the import as evidenced below withmesa.time.RandomActivation. You can see the different time classes at mesa.time. ↩ -

Other types of space available include

HexGrid,NetworkGrid, and the previously mentionedContinuousSpace. Similar tomesa.timecontext is retained withmesa.space.[enter class]. You can see the different classes atmesa.space. ↩ -

Mehdizadeh, Milad, Trond Nordfjaern, und Christian A. Klöckner. (2022). “A systematic review of the Agent-Based Modelling/simulation paradigm in mobility transition“. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 184:122011, p.8-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.122011. ↩

-

Avena-Koenigsberger, Andrea, Joaquín Goñi, Ricard Solé, and Olaf Sporns. “Network Morphospace.” Journal of The Royal Society Interface 12, no. 103 (2015): 20140881. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2014.0881. ↩

-

Grimm, Volker and Railsback, Steven F. and Vincenot, Christian E. and Berger, Uta and Gallagher, Cara and DeAngelis, Donald L. and Edmonds, Bruce and Ge, Jiaqi and Giske, Jarl and Groeneveld, Jürgen and Johnston, Alice S.A. and Milles, Alexander and Nabe-Nielsen, Jacob and Polhill, J. Gareth and Radchuk, Viktoriia and Rohwäder, Marie-Sophie and Stillman, Richard A. and Thiele, Jan C. and Ayllon, Daniel (2020). The ODD Protocol for Describing Agent-Based and Other Simulation Models: A Second Update to Improve Clarity, Replication, and StructuralRealism’ Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation 23 (2) 7. https://doi.org/10.18564/jasss.4259. ↩