Contents

- Lesson Goals

- For Whom is this Useful?

- Installing R

- Using the R Console

- Using Data Sets

- Basic Functions

- Working with Larger Data Sets

- Matrices

- Solutions

- Loading Your Own Data Sets into R

- Saving Data in R

- Summary and Next Steps

- Endnotes

Lesson Goals

As more and more historical records are digitized, having a way to quickly analyze large volumes of tabular data makes research faster and more effective.

R is a programming language with strengths in statistical analyses. As such, it can be used to complete quantitative analysis on historical sources, including but not limited to statistical tests. Because you can repeatedly re-run the same code on the same sources, R lets you analyze data quickly and produces repeatable results. Because you can save your code, R lets you re-purpose or revise functions for future projects, making it a flexible part of your toolkit.

This tutorial presumes no prior knowledge of R. It will go through some of the basic functions of R and serves as an introduction to the language. It will take you through the installation process, explain some of the tools that you can use in R, as well as explain how to work with data sets while doing research. The tutorial will do so by going through a series of mini-lessons that will show the kinds of sources R works well with and examples of how to do calculations to find information that could be relevant to historical research. The lesson will also cover different input methods for R such as matrices and using CSV files.

For Whom is this Useful?

R is ideal for analyzing larger data sets that would take too long to compute manually. Once you understand how to write some of the basic functions and how to import your own data files, you can analyze and visualize the data quickly and efficiently.

While R is a great tool for tabular data, you may find using other approaches to analyse non-tabular sources (such as newspaper transcriptions) more useful. If you are interested in studying these types of sources, take a look at some of the other great lessons of the Programming Historian.

Installing R

R is a programming language and environment for working with data. It can be run using the R console as well as on the command-line or the R Studio Interface. This tutorial will focus on using the R console. To get started with R, download the program from The Comprehensive R Archive Network. R is compatible with Linux, Mac, and Windows.

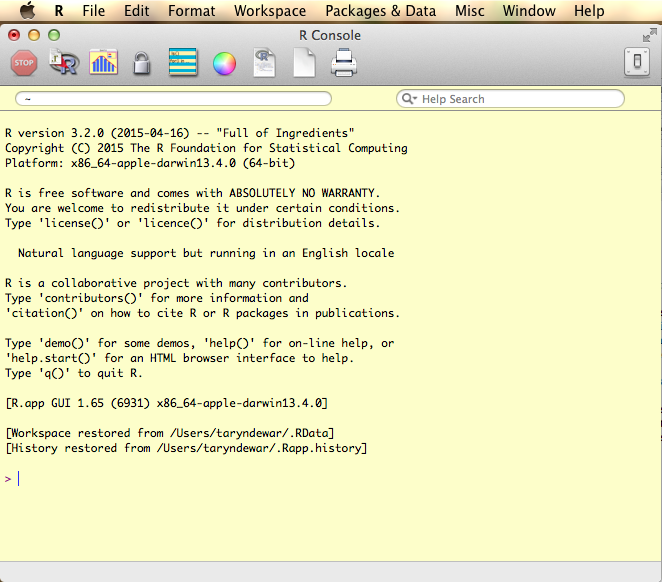

When you first open the R console, it will open in a window that looks like this:

The R console on a Mac.

Using the R Console

The R console is a great place to start working if you are new to R because it was designed specifically for the language and has features that are specific to R.

The console is where you will type commands. To clear the initial screen, go to ‘Edit’ in the menu bar and select ‘Clear Console’. This will start you with a fresh page. You can also change the appearance of the console by clicking on the colour wheel at the top of the console on a Mac, or by selecting ‘GUI Preferences’ in the ‘Edit’ menu on a PC. You can adjust the background screen colour and the font colours for functions, as well.

Using Data Sets

Before working with your own data, it helps to get a sense of how R works by using the built-in data sets. You can search through the data sets by entering data() into the console. This will bring up the list of all of the available data sets in a separate window. This list includes the titles of all of the different data sets as well as a short description about the information in each one.

First, you need to load the AirPassengers data set into your R session. Type data(AirPassengers) and hit Enter1. To view the data set, type in AirPassengers on the next line and hit Enter again. This will print a table showing the number of passengers who flew on international airlines between January 1949 and December 1960, in thousands. You should see:

> data(AirPassengers)

> AirPassengers

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec

1949 112 118 132 129 121 135 148 148 136 119 104 118

1950 115 126 141 135 125 149 170 170 158 133 114 140

1951 145 150 178 163 172 178 199 199 184 162 146 166

1952 171 180 193 181 183 218 230 242 209 191 172 194

1953 196 196 236 235 229 243 264 272 237 211 180 201

1954 204 188 235 227 234 264 302 293 259 229 203 229

1955 242 233 267 269 270 315 364 347 312 274 237 278

1956 284 277 317 313 318 374 413 405 355 306 271 306

1957 315 301 356 348 355 422 465 467 404 347 305 336

1958 340 318 362 348 363 435 491 505 404 359 310 337

1959 360 342 406 396 420 472 548 559 463 407 362 405

1960 417 391 419 461 472 535 622 606 508 461 390 432

You can now use R to answer a number of questions based on this data. For example, what were the most popular months to fly? Was there an increase in international travel over time? You could probably find the answers to such questions simply by scanning this table, but not as quickly as the computer. And what if there were a lot more data?

Basic Functions

R can be used to calculate a number of values that might be useful to you while doing research on a data set. For example, you can find the mean, median, minimum, and maximum values in a data set. To find the mean and median values in the data set, you can enter mean(AirPassengers) and median(AirPassengers), respectively, into the console. What if you wanted to calculate more than just one value at a time? To produce a summary of the data, enter summary(AirPassengers) into the console. This will give you the minimum and maximum data points, as well as the mean, median and first and third quartile values.

summary(AirPassengers)

Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

104.0 180.0 265.5 280.3 360.5 622.0

Running a summary shows us that the minimum number of passengers between January 1949 and December 1960 was 104,000 and that the maximum number of passengers was 622,000. The mean value shows us that approximately 280,300 people travelled per month during the time the data was collected for. These values can be useful for seeing the degree of variation in number of passengers over time.

Using the summary() function is a good way to get an overview of the entire data set, but what if you are interested in a subset of the data, such as a particular year or certain months? You can select different data points (such as a particular month) and ranges (such as a particular year) in R to calculate many different values. For example, you can add the number of passengers for two months together to determine the total number of passengers over that period of time.

Try adding the first two values from the AirPassengers data in the console and then hit ‘Enter’. You should see two lines that read:

> 112+118

[1] 230

This would give you the total number of passengers (in hundreds of thousands) who flew in January and February of 1949.

R can do more than just simple arithmetic. You can create objects, or variables, to represent numbers and expressions. For example, you could name the January 1949 value a variable such as Jan1949. Type Jan1949<- 112 into the console and then Jan1949 on the next line. The <- notation assigns the value 112 to the variable Jan1949. You should see:

> Jan1949 <- 112

> Jan1949

[1] 112

R is case sensitive, so be careful that you use the same notation when you use the variables you have assigned (or named) in other actions. See Rasmus Bååth’s article, The State of Naming Conventions in R, for more information on how to best name variables.

To remove a variable from the console, type rm() with the variable you want to get rid of inside the brackets, and press Enter. To see all of the variables you have assigned, type ls() into the console and press Enter - this will help you avoid using the same name for multiple variables. This is also important because R stores all of the objects you create in its memory, so even if you cannot see a variable named x in the console, it may have been created before and you could accidentally overwrite it when assigning another variable.

Here is the list of variables we have created so far:

> ls()

[1] "AirPassengers" "Jan1949"

We have the AirPassengers variable and the Jan1949 variable. If we remove the Jan1949 variable and retype ls(), we will see:

> rm(Jan1949)

> ls()

[1] "AirPassengers"

If at any time you become stuck with a function or cannot fix an error, type help() into the console to open the help page. You can also find general help by using the ‘Help’ menu at the top of the console. If you want to change something in the code you have already written, you can re-type the code on a new line. To save time, you can also use the arrow keys on your keyboard to scroll up and down in the console to find the line of code you want to change.

You can use letters as variables but when you start working with your own data it may be easier to assign names that are more representative of that data. Even with the AirPassengers data, assigning variables that correlate with specific months or years would make it easier to know exactly which points you are working with.

Practice

A. Assign variables for the January 1950 and January 1960 AirPassengers data points. Add the two variables together on the next line.

B. Use the variables you just created to find the difference between air travellers in 1960 versus 1950.

Solutions

A. Assign variables for the January 1950 and January 1960 AirPassengers data points. Add the two variables together on the next line.

> Jan1950<- 115

> Jan1960<- 417

> Jan1950+Jan1960

[1] 532

This means that 532,000 people travelled on international flights in January 1950 and January 1960.

B. Use the variables you just created to find the difference between air travellers in 1960 versus 1950:

> Jan1960-Jan1950

[1] 302

This means that 302,000 more people travelled on international flights in January 1960 than in January 1950.

Setting variables for individual data points can be tedious, especially if the names you give them are quite long. However, the process is similar for assigning a range of values to one variable such as all of the data points for one year. We do this by creating lists called ‘vectors’ using the c command. c stands for ‘combine’ and lets us link numbers together into a common variable. For example, you could create a vector for the AirPassenger data for 1949 called ‘Air49’:

> Air49<- c(112,118,132,129,121,135,148,148,136,119,104,118)

Each item is accessible using the name of the variable and its index position (starting at 1). In this case, Air49[2] contains the value that corresponds to February 1949 - 118.

> Air49[2]

[1] 118

You can create a list of consecutive values using a semicolon. For example:

> y<- 1:10

> y

[1] 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Using this knowledge, you could use the following expression to define a variable for the 1949 AirPassengers data:

> Air49<- AirPassengers[1:12]

> Air49

[1] 112 118 132 129 121 135 148 148 136 119 104 118

Air49 selected the first twelve terms in the AirPassengers data set. This gives you the same result as above, but takes less time and also reduces the chance that a value will be transcribed incorrectly.

To get the total number of passengers for 1949, you can add all of the terms in the vector together by using the sum() function:

sum(Air49)

[1] 1520

Therefore, the total number of passengers in 1949 was approximately 1,520,000.

Finally, the ‘length()’ function makes it possible to discern the number of items in a vector:

length(Air49)

[1] 12

Practice

- Create a variable for the 1950

AirPassengersdata. - Print out the second term in the 1950 series.

- What is the length of the sequence in Question 2?

- What is the total number of people who flew in 1950?

Solutions

1.

Air50<- AirPassengers[13:24]

Air50

[1] 115 126 141 135 125 149 170 170 158 133 114 140

2.

Air50[2]

[1] 126

3.

length(Air50)

[1] 12

4.

sum(Air50)

[1] 1676

If you were to create variables for all of the years in the data set, you could then use some of the tools we’ve looked at to determine the number of people travelling by plane over time. Here is a list of variables for 1949 to 1960, followed by the total number of passengers for each year:

Air49 <- AirPassengers[1:12]

Air50 <- AirPassengers[13:24]

Air51 <- AirPassengers[25:36]

Air52 <- AirPassengers[37:48]

Air53 <- AirPassengers[49:60]

Air54 <- AirPassengers[61:72]

Air55 <- AirPassengers[73:84]

Air56 <- AirPassengers[85:96]

Air57 <- AirPassengers[97:108]

Air58 <- AirPassengers[109:120]

Air59 <- AirPassengers[121:132]

Air60 <- AirPassengers[133:144]

sum(Air49)

[1] 1520

sum(Air50)

[1] 1676

sum(Air51)

[1] 2042

sum(Air52)

[1] 2364

sum(Air53)

[1] 2700

sum(Air54)

[1] 2867

sum(Air55)

[1] 3408

sum(Air56)

[1] 3939

sum(Air57)

[1] 4421

sum(Air58)

[1] 4572

sum(Air59)

[1] 5140

sum(Air60)

[1] 5714

From this information, you can see that the number of passengers increased every year. You could go further with this data to determine if there was growing interest in vacations at certain times of year, or even the percentage increase in passengers over time.

Working with Larger Data Sets

Notice that the above example would not scale well for a large data set - counting through all of the data points to find the right ones would be very tedious. Think about what would happen if you were looking for information for year 96 in a data set with 150 years worth of data.

You can actually select specific rows or columns of data if the data set is in a certain format. Load the mtcars data set into the console:

> data(mtcars)

> mtcars

mpg cyl disp hp drat wt qsec vs am gear carb

Mazda RX4 21.0 6 160.0 110 3.90 2.620 16.46 0 1 4 4

Mazda RX4 Wag 21.0 6 160.0 110 3.90 2.875 17.02 0 1 4 4

Datsun 710 22.8 4 108.0 93 3.85 2.320 18.61 1 1 4 1

Hornet 4 Drive 21.4 6 258.0 110 3.08 3.215 19.44 1 0 3 1

Hornet Sportabout 18.7 8 360.0 175 3.15 3.440 17.02 0 0 3 2

Valiant 18.1 6 225.0 105 2.76 3.460 20.22 1 0 3 1

Duster 360 14.3 8 360.0 245 3.21 3.570 15.84 0 0 3 4

Merc 240D 24.4 4 146.7 62 3.69 3.190 20.00 1 0 4 2

Merc 230 22.8 4 140.8 95 3.92 3.150 22.90 1 0 4 2

Merc 280 19.2 6 167.6 123 3.92 3.440 18.30 1 0 4 4

Merc 280C 17.8 6 167.6 123 3.92 3.440 18.90 1 0 4 4

Merc 450SE 16.4 8 275.8 180 3.07 4.070 17.40 0 0 3 3

Merc 450SL 17.3 8 275.8 180 3.07 3.730 17.60 0 0 3 3

Merc 450SLC 15.2 8 275.8 180 3.07 3.780 18.00 0 0 3 3

Cadillac Fleetwood 10.4 8 472.0 205 2.93 5.250 17.98 0 0 3 4

Lincoln Continental 10.4 8 460.0 215 3.00 5.424 17.82 0 0 3 4

Chrysler Imperial 14.7 8 440.0 230 3.23 5.345 17.42 0 0 3 4

Fiat 128 32.4 4 78.7 66 4.08 2.200 19.47 1 1 4 1

Honda Civic 30.4 4 75.7 52 4.93 1.615 18.52 1 1 4 2

Toyota Corolla 33.9 4 71.1 65 4.22 1.835 19.90 1 1 4 1

Toyota Corona 21.5 4 120.1 97 3.70 2.465 20.01 1 0 3 1

Dodge Challenger 15.5 8 318.0 150 2.76 3.520 16.87 0 0 3 2

AMC Javelin 15.2 8 304.0 150 3.15 3.435 17.30 0 0 3 2

Camaro Z28 13.3 8 350.0 245 3.73 3.840 15.41 0 0 3 4

Pontiac Firebird 19.2 8 400.0 175 3.08 3.845 17.05 0 0 3 2

Fiat X1-9 27.3 4 79.0 66 4.08 1.935 18.90 1 1 4 1

Porsche 914-2 26.0 4 120.3 91 4.43 2.140 16.70 0 1 5 2

Lotus Europa 30.4 4 95.1 113 3.77 1.513 16.90 1 1 5 2

Ford Pantera L 15.8 8 351.0 264 4.22 3.170 14.50 0 1 5 4

Ferrari Dino 19.7 6 145.0 175 3.62 2.770 15.50 0 1 5 6

Maserati Bora 15.0 8 301.0 335 3.54 3.570 14.60 0 1 5 8

Volvo 142E 21.4 4 121.0 109 4.11 2.780 18.60 1 1 4 2

This data set gives an overview of Motor Trend Car Road Tests from the 1974 Motor Trend magazine 2. It has information about how many miles per gallon a car could travel, the number of engine cylinders each car has, horsepower, rear axle ratio, weight, and a number of other features for each model. The data could be used to find out which of these features made each type of car more or less safe for drivers over time.

You can select columns by entering the name of the data set followed by square brackets and the number of either the row or column of data you are interested in. To sort out the rows and columns, think of dataset[x,y], where dataset is the data you are working with, x is the row, and y is the column.

If you were interested in the first row of information in the mtcars data set, you would enter the following into the console:

> mtcars[1,]

mpg cyl disp hp drat wt qsec vs am gear carb

Mazda RX4 21 6 160 110 3.9 2.62 16.46 0 1 4 4

To see a column of the data, you could enter:

> mtcars[,2]

[1] 6 6 4 6 8 6 8 4 4 6 6 8 8 8 8 8 8 4 4 4 4 8 8 8 8 4 4 4 8 6 8 4

This would show you all of the values under the cyl category. Most of the car models have either 4, 6, or 8 cylinder engines. You can also select single data points by entering values for both x and y:

> mtcars[1,2]

[1] 6

This returns the value in the first row, second column. From here, you could run a summary on one row or column of data without having to count the number of terms in the data set. For example, typing summary(mtcars[,1]) into the console and pressing ‘Enter’ would give the summary for the miles per gallon the different cars use in the mtcars data set:

> summary(mtcars[,1])

Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

10.40 15.42 19.20 20.09 22.80 33.90

The summary indicates that the maximum fuel efficiency was 33.9 miles per gallon, from the Toyota Corolla and the least efficient was the Lincoln Continental which only got 10.4 miles per gallon. We can find the cars that match the value points by looking back at the table. It’s much easier to find a specific value than to try to do the math in your head or search through a spreadsheet.

Matrices

Now that you have a better understanding of how some of the basic functions in R work, we can look at ways of using those functions on our own data. This includes building matrices using small data sets. The benefit of knowing how to construct matrices in R is that if you only have a few data points to work with, you could simply create a matrix instead of a CSV that you would then have to import. One of the simplest ways to build a matrix is to create at least two variables or vectors and then bind them together. For example, let’s look at some data from the Old Bailey:

data set for criminal cases in each decade between 1670 and 1800.](/images/r-basics-with-tabular-data/Intro-to-R-2.png)

The Old Bailey data set for criminal cases in each decade between 1670 and 1800.

The Old Bailey contains statistics and information about criminal cases between 1674 and 1913 that were held by London’s Central Criminal Court. If we wanted to look at the total number of theft and violent theft offences for the decades between 1670 and 1710, we could put those numbers into a matrix.

To do this, let’s create the variables Theft and ViolentTheft using the totals from each decade as data points:

Theft <- c(2,30,38,13)

ViolentTheft <- c(7,20,36,3)

To create a matrix, we can use the cbind() function (column bind). This binds Theft and ViolentTheft together in columns, represented by Crime below.

Theft <- c(2,30,38,13)

ViolentTheft <- c(7,20,36,3)

Crime <- cbind(Theft,ViolentTheft)

> Crime

Theft ViolentTheft

[1,] 2 7

[2,] 30 20

[3,] 38 36

[4,] 13 3

You can set a matrix using rbind() as well. rbind() binds the data together in rows (row bind). Look at the difference between Crime and Crime2:

> Crime2 <- rbind(Theft,ViolentTheft)

> Crime2

[,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

Theft 2 30 38 13

ViolentTheft 7 20 36 3

The second matrix could also be created by using the expression t(Crime), which creates the inverse of Crime.

You can also construct a matrix using the matrix() function. It lets you turn a string of numbers such as the number of thefts and violent thefts committed into a matrix if you hadn’t created separate variables for the data points:

> matrix(c(2,30,3,4,7,20,36,3),nrow=2)

[,1] [,2] [,3] [,4]

[1,] 2 3 7 36

[2,] 30 4 20 3

>matrix(c(2,30,3,4,7,20,36,3),ncol=2)

[,1] [,2]

[1,] 2 7

[2,] 30 20

[3,] 3 36

[4,] 4 3

The first part of the function is the list of numbers. After that, you can determine how many rows (nrow=) or columns (ncol=) the matrix will build.

The apply() function allows you to perform the same function on every row or column of a matrix. There are three parts to the apply function: first you have to select the matrix you are using, the terms you want to use, and what function you are performing on a matrix:

> Crime

Theft ViolentTheft

[1,] 2 7

[2,] 30 20

[3,] 38 36

[4,] 13 3

> apply(Crime,1,mean)

[1] 4.5 25.0 37.0 8.0

The above example shows the apply function used on the Crime matrix to calculate the mean of each row, and so the average number of combined theft and violent theft crimes that were committed in each decade. If you want to find the mean of each column, you would use 2 instead of 1 inside of the function:

> apply(Crime,2,mean)

Theft ViolentTheft

20.75 16.50

This shows you the average number of theft crimes and then violent theft crimes between decades.

Practice

- Create a matrix with two columns using the following data from the Breaking Peace and Killing crimes between 1710 and 1730 from the Old Bailey chart above:

c(2,3,3,44,51,17) - Use the

cbind()function to joinBreakingPeace <- c(2,3,3)andKilling <- c(44,51,17)together. - Calculate the mean of each column for the above matrix using the

apply()function.

Solutions

1.

> matrix(c(2,3,3,44,51,17),ncol=2)

[,1] [,2]

[1,] 2 44

[2,] 3 51

[3,] 3 17

2.

> BreakingPeace <- c(2,3,3)

> Killing <- c(44,51,17)

> PeaceandKilling <- cbind(BreakingPeace,Killing)

> PeaceandKilling

BreakingPeace Killing

[1,] 2 44

[2,] 3 51

[3,] 3 17

3.

> apply(PeaceandKilling,2,mean)

BreakingPeace Killing

2.666667 37.333333

Using matrices can be useful when you are working with small amounts of data. However, it isn’t always the best option because a matrix can be hard to read. Sometimes it is easier to create your own file using a spreadsheet programme such as Excel or Open Office to ensure that all of the information you want to study is organized and import that file into R.

Loading Your Own Data Sets into R

Now that you have practiced with simple data, you’re probably ready to try working with your own. Your data are likely in a spreadsheet. So how can you work with this data in R? There are a few different ways you can do this. The first is to load an Excel spreadsheet directly into R. Another way is to import a CSV or TXT file into R.

To directly load an Excel file into the R console, you first have to install the readxl package. To do this, type install.packages("readxl") into the console and press Enter. You may have to check that the package is loaded into the console by going into the ‘Packages & Data’ tab in the menu bar, selecting ‘Package Manager’, and then clicking the box beside the readxl package. From there, you can select a file and load it into R. Below is an example of what loading a simple Excel file might look like:

> x <- read_excel("Workbook2.xlsx")

> x

a b

1 1 5

2 2 6

3 3 7

4 4 8

After the read_excel command, you are entering the name of the file you are selecting. The numbers below correspond to the data in the sample spreadsheet I used. Notice how the rows are numbered and my columns are labelled as I had them in the original spreadsheet.

When you are loading data into R, make sure that the file you are accessing is within the directory on your computer that you are working from. To check this, you can type dir() into the console or getwd(). You can change the directory if needed by going under the ‘Miscellaneous’ tab in the title bar on your screen and then selecting what you want to set as the directory for R. If you don’t do this R will not be able to find the file properly.

Another way to load data into R is to use a CSV file. A CSV (comma separated value) file will show the values in rows and columns and separates those values with a comma. You can save any document you create in Excel as a .csv file and then load it into R. To use a CSV file in R, assign a name to the file using the <- command and then type read.csv(file="file-name.csv",header=TRUE,sep=",") into the console. file-name tells R which file to select, while setting the header to TRUE says that the first row are headings and not variables. sep means that there is a comma between every number and line.

Normally, a CSV could have quite a bit of information in it. To start though, try creating a CSV file in Excel using the Old Bailey data we were using for the matrices. Set up columns for the dates between 1710 and 1730 as well as the number of Breaking the Peace and Killing crimes recorded for those decades. Save the file as “OldBailey.csv” and try loading it into R using the above steps. You will see:

> read.csv(file="OldBailey.csv",header=TRUE,sep=",")

Date Breaking.Peace Killing

1 1710 2 44

2 1720 3 51

3 1730 4 17

Now you could access the data in R and do any calculations to help you study the data. The CSV files can also be much more complex than this example, so any data set you were working with in your own study could also be opened in R.

TXT (or text files) can be imported into R in a similar way. Using the command read.table(), you can load text files into R, following the same syntax as in the example above.

Saving Data in R

Now that you’ve loaded data into R and know a few ways to work with the data, what happens if you want to save it to another format? The write.xlsx() function allows you to do just that - taking data from R and saving it into an Excel file. Try writing the Old Bailey file into an Excel file. First you will need to load the package and then you can create the file after creating a variable for the Old Bailey data:

library(xlsx)

write.xlsx(x = OldBailey, file = "OldBailey.xlsx", sheetName = "OldBailey", row.names = TRUE)

Summary and Next Steps

This tutorial has explored the basics of using R to work with tabular research data. R can be a very useful tool for humanities and social science research because the data analysis is reproducible and allows you to analyze data quickly without having to set up a complicated system. Now that you know a few of the basics of R, you can explore some of the other functions of the program, including statistical computations, producing graphs, and creating your own functions.

For more information on R, visit the R Manual.

There are also a number of other R tutorials online including:

- R: A self-learn tutorial - this tutorial goes through a series of functions and provides exercises to practice skills.

- DataCamp Introduction to R - this is a free online course that gives you feedback on your code to help identify errors and learn how to write code more efficiently.

Finally, a great resource for digital historians is Lincoln Mullen’s Digital History Methods in R. It is a draft of a book written specifically on how to use R for digital history work.