Contents

- An Introduction to Twitter Bots with Tracery

- Planning: What will your bot do?

- Get a twitter account for your bot and connect it to Cheap Bots Done Quick

- Going further with Tracery

- Other Bot Tutorials

- References

An Introduction to Twitter Bots with Tracery

This lesson explains how to create simple twitterbots using the Tracery generative grammar and the Cheap Bots Done Quick service. Tracery exists in multiple languages and can be integrated into websites, games, bots. You may fork it on github here.

Why bots?

Strictly speaking, a twitter bot is a piece of software for automated controlling a Twitter account. When thousands of these are created and are tweeting more or less the same message, they have the ability to shape discourse on Twitter which then can influence other media discourses. Bots of this kind can even be seen as credible sources of information. Projects such as Documenting the Now are creating tools to allow researchers to create and query archives of social media around current events - and which will naturally contain many bot-generated posts. In this tutorial, I want to demonstrate how one can build a simple twitterbot so that, knowing how they operate, historians may more easily spot the bots in our archives - and perhaps counter with bots of their own.

But I believe also that there is space in digital history and the digital humanities more generally for creative, expressive, artistic work. I belive that there is space for programming historians to use the affordances of digital media to create things that could not otherwise exist to move us, to inspire us, to challenge us. There is room for satire; there is room for comment. With Mark Sample, I believe that there is a need for ‘bots of conviction’.

These are protest bots, bots so topical and on-point that they can’t be mistaken for anything else. Per Sample, such bots should be

topical – “They are about the morning news — and the daily horrors that fail to make it into the news.”

data-based – “They draw from research, statistics, spreadsheets, databases. Bots have no subconscious, so any imagery they use should be taken literally”

cumulative – “The repetition builds on itself, the bot relentlessly riffing on its theme, unyielding and overwhelming, a pile-up of wreckage on our screens.”

oppositional – “protest bots take a stand. Society being what it is, this stance will likely be unpopular, perhaps even unnerving”

uncanny – “The appearance of that which we had sought to keep hidden.”

I want to see more protest bots, bots that confront us with hard truths, bots that, in their inhuman persistence, call out for justice. Caleb McDaniel’s every 3 minutes shames us with its unrelenting reminder that every three minutes, a human being was sold into slavery in the Antebellum South.

A screenshot of the Every3Minutes Twitter page

every3minutes alone is reason enough to want to build a history bot.

Some suggestions to get you thinking, from individuals on Twitter who responded to my question about what the bots of conviction for history and archaeology might look like

@electricarchaeo a bot tweeting full-resolution images of cultural heritage locked behind tile viewers and fraudulent copyright claims by their holding inst? — Ryan Baumann (@ryanfb) April 22, 2017

@electricarchaeo A bot tweeting pictures of Native American sacred places that have been desecrated in the name of corporate greed. — Cory Taylor (@CoryTaylor_) April 22, 2017

@electricarchaeo A bot tweeting the identities of historical assets given inheritance #tax exemption because they are “available” to public view — Sarah Saunders (@Tick_Tax) April 22, 2017

@electricarchaeo A bot tweeting the names of slaves owned by top universities, or of those who built government buildings like the White House. — Cory Taylor (@CoryTaylor_) April 22, 2017

@electricarchaeo Every time someone says “since the beginning of time, humans have” automatically responding BULLSHIT — Colleen Morgan (@clmorgan) April 22, 2017

@electricarchaeo A bot imagining the reactions of Afghans, Iraqis, Syrians, Yemenis, when their family members are killed by drone attacks. — Cory Taylor (@CoryTaylor_) April 22, 2017

Given that so much historical data is expressed on the web as JSON, a bit of digging should find you data that you can actually fold into your bot.

My method is that of the bricoleur, the person who adapts and pastes together the bits and bobs of code that he finds; in truth, most programming functions this way. There are many packages available that will interface with Twitter’s API, in various languages. There is little ‘programming’ in this lesson in the sense of writing bots in (for instance) Python. In this introductory lesson, I will show you how to build bots that tell stories, that write poetry, that do wonderful things using Tracery.io as our generative grammar, in conjunction with the Cheap Bots Done Quick service to host the bot. For more tutorials on building and hosting Twitter bots with other services, see the Botwiki tutorial list.

My most successful bot has been @tinyarchae, a bot that tweets scenes from a horrible dsyfunctional archaeological excavation project. Every archaeological project deals with problems of sexism, abuse, and bad faith; @tinyarchae pushes the stuff of conference whispers to a ridiculous extreme. It is a caricature that contains a kernel of uncomfortable truth. Other bots I have built glitch archaeological photography; one is actually useful, in that it is tweeting out new journal articles in archaeology and so serves as a research assistant. (For more thoughts on the role bots play in public archaeology, see this keynote from the Public Archaeology Twitter Conference).

Planning: What will your bot do?

We begin with pad and paper. As a child in elementary school, one activity we often did to learn the basics of English grammar was called ‘mad-libs’ (as in, ‘silly - mad - ad libs’). The teacher performing this activity would ask the class to, say, list a noun, then and adverb, then a verb, and then another adverb. Then on the other side of the sheet there would be a story with blank spaces like this:

“Susie the _noun_ was _adverb_ _verb_ the _noun_.”

and students would fill in the blanks appropriately. It was silly; and it was fun. Twitterbots are to madlibs what sports cars are to horse and wagons. The blanks that we might fill in could be values in svg vector graphics. They could be numbers in numeric file names (and thus tweet random links to an open database, say). They could be, yes, even nouns and adverbs. Since Twitterbots live on the web, the building blocks that we put together can be more than text (although, for the time being, text will be easiest to work with).

We are going to start by sketching out a replacement grammar. The conventions of this grammar were developed by Kate Compton (@galaxykate on Twitter); it’s called Tracery.io. It can be used as a javascript library in webpages, in games, and in bots. A replacement grammar works rather similarly to the madlibs you might remember as a child.

In order to make it clear what the _grammar_ is doing, we are going to _not_ create a history bot for the time being. I want to make it clear what the grammar does, and so we will build something surreal to surface how that grammar works.

Let’s imagine that you would like to create a bot that speaks with the voice of a potted plant - call it, plantpotbot. What kinds of things might plantpotbot say? Jot down some ideas-

- I am a plant in a pot. How boring it is!

- Please water me. I’m begging you.

- This pot. It’s so small. My roots, so cramped!

- I turned towards the sun. But it was just a lightbulb

- I’m so lonely. Where are all the bees?

Now, let’s look at how these sentences have been constructed. We are going to replace words and phrases with symbols so that we can regenerate the original sentences. There are a number of sentences that being with ‘I’. We can begin to think of an ‘being’ symbol:

"being": "am a plant","am begging you","am so lonely","turned towards the sun"

This notation is saying to us that the symbol “being” can be replaced by (or is equivalent to) the phrases “am a plant”, “am begging you” and so on.

We can mix symbols and text, in our bot. If we tell the bot to start with the word “I”, we can insert the symbol ‘being’ after it and complete the phrase with “am a plant” or “turned towards the sun” and the sentence will make grammatical sense. Let’s build another symbol; perhaps we call it ‘placewhere’:

"placewhere": "in a pot","on the windowsill","fallen over"

(“placewhere” is the symbol and “in a pot” and so on are the rules that replace it)

Now, in our sentences from our brainstorm, we never used the phrase, ‘on the windowsill’, but once we identified ‘in a pot’, other potential equivalent ideas jump out. Our bot will eventually use these symbols to make sentences. The symbols - ‘being’, ‘placewhere’ - are like our madlibs when they asked for a list of nouns, adverbs and so on. Imagine then we pass the following to our bot:

"I #being# #placewhere#"

Possible outcomes will be:

- I am so lonely on the windowsill

- I am so lonely in a pot

- I turned toward the sun fallen over

With tweaking, and breaking the units of expression into smaller symbols, we can fix any expressive infelicities (or indeed, decide to leave them in to make the voice more ‘authentic’.)

Prototyping with a Tracery editor

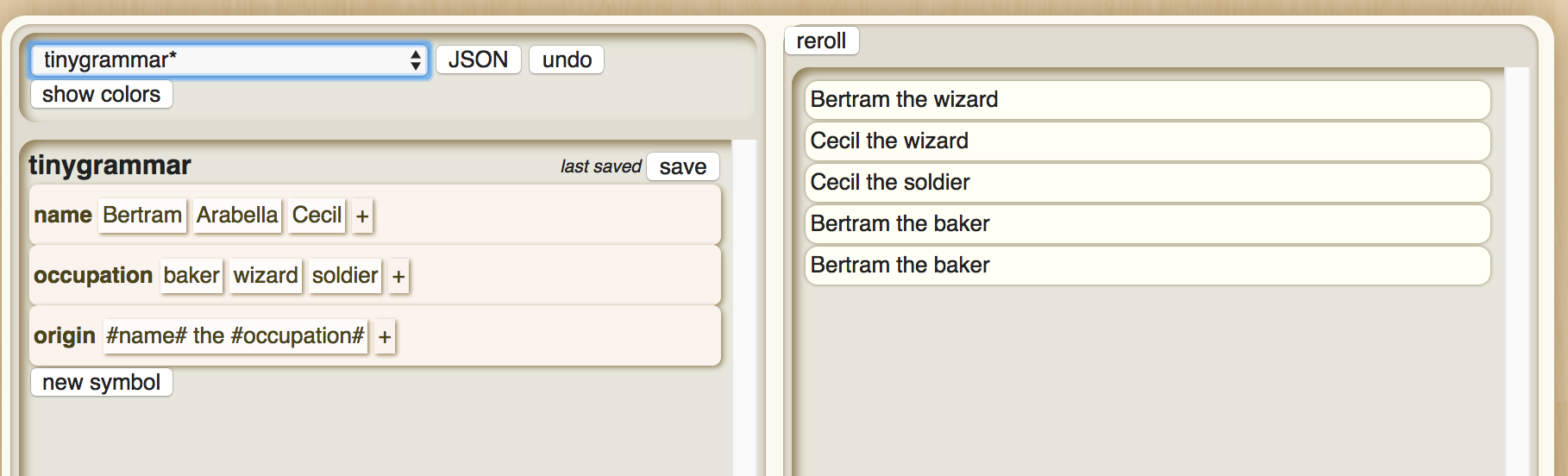

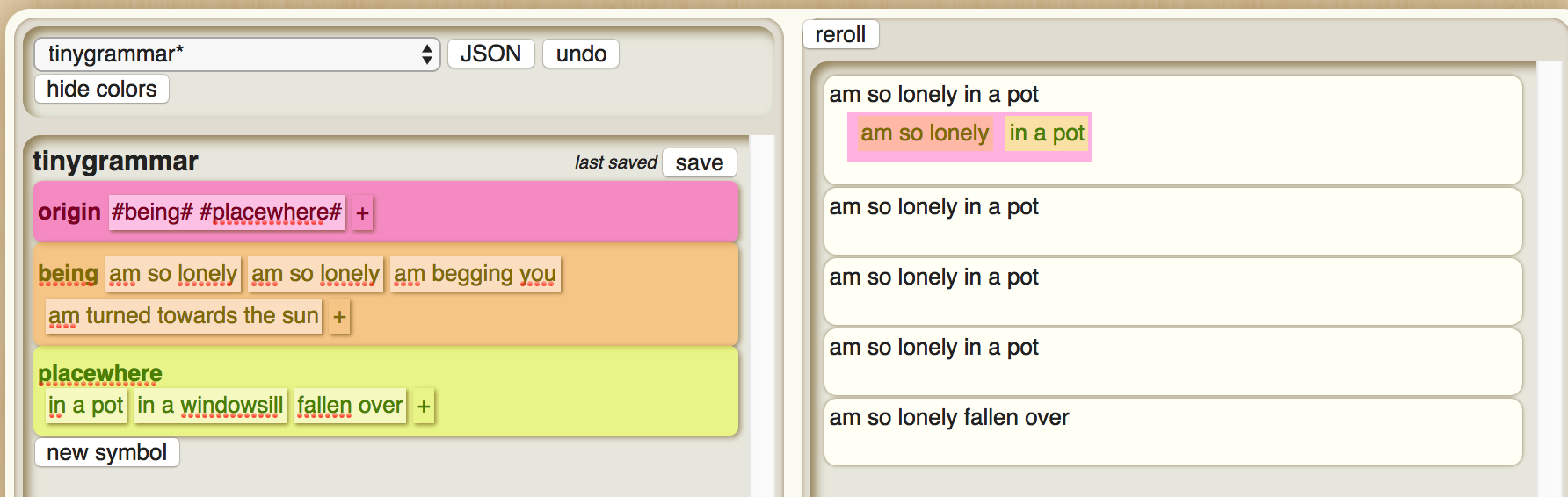

In order to work out the kinks in plantpotbot, we used the Tracery editor at Brightspiral, which unfortunately no longer exists. Now, you might want to try the following alternative at https://tracery.io/editor/. The editor visualizes the way the symbols and rules of the grammar interact (how they are nested, and the kinds of output your grammar will generate). Open the editor in a new window. You should see this:

The Tracery Editor at Brightspiral.com

The dropdown menu at the top-left, marked ‘tinygrammar’, has some other example grammars that one can explore; they show just how complicated Tracery can become. For the time being, remain with ‘tinygrammar’. One of the nice things about this editor is that you can press the ‘show colors’ button, which will color code each symbol and its rules, color-coding the generated text so that you can see which element belongs to what symbol.

If you double-click on a symbol in the default grammar (name or occupation) and hit your delete key, you will remove the symbol from the grammar. Do so for ‘name’ and ‘occupation’, leaving only ‘origin’. Now, add a new symbol by clicking on the ‘new symbol’ button. Click on the name (symbol1) and rename it being. Click the + sign and add some of our rules above. Repeat for a new symbol called placewhere.

Building the grammar for plantpotbot

As you do that, the editor will flash an error message at the top right, ‘ERROR: symbol ‘name’ not found in tinygrammar’. This is because we deleted name, but the symbol origin has as one of its rules the symbol name! This is interesting: it shows us that we can nest symbols within rules. Right? We could have a symbol called ‘character’, and character could have sub-symbols called ‘first name’, ‘last name’ and ‘occupation’ (and each of these containing an appropriate list of first names and last names and occupations). Each time the grammar was run, you’d get e.g. ‘Shawn Graham Archaeologist’ and stored in the ‘character’ symbol

The other interesting thing here is that origin is a special symbol. It’s the one from which the text is ultimately generated (the grammar is flattened here). So let’s change the origin symbol’s rule so that plantpotbot may speak. (When you reference another symbol within a rule, you wrap it with # marks, so this should read: #being# #placewhere#).

It still is missing something - the word ‘I’. You can mix ordinary text into the rules. Go ahead and do that now - press the + beside the rule for the origin symbol, and add the word ‘I’ so that the origin now reads I #being# #placewhere#. Perhaps your plantbot speaks with a poetic diction by reversing #placewhere# #being#.

If you press ‘save’ in the editor, your grammar will be timestamped and will appear in the dropdown list of grammars. It’s being saved to your browser’s cache; if you clear the cache, you will lose it.

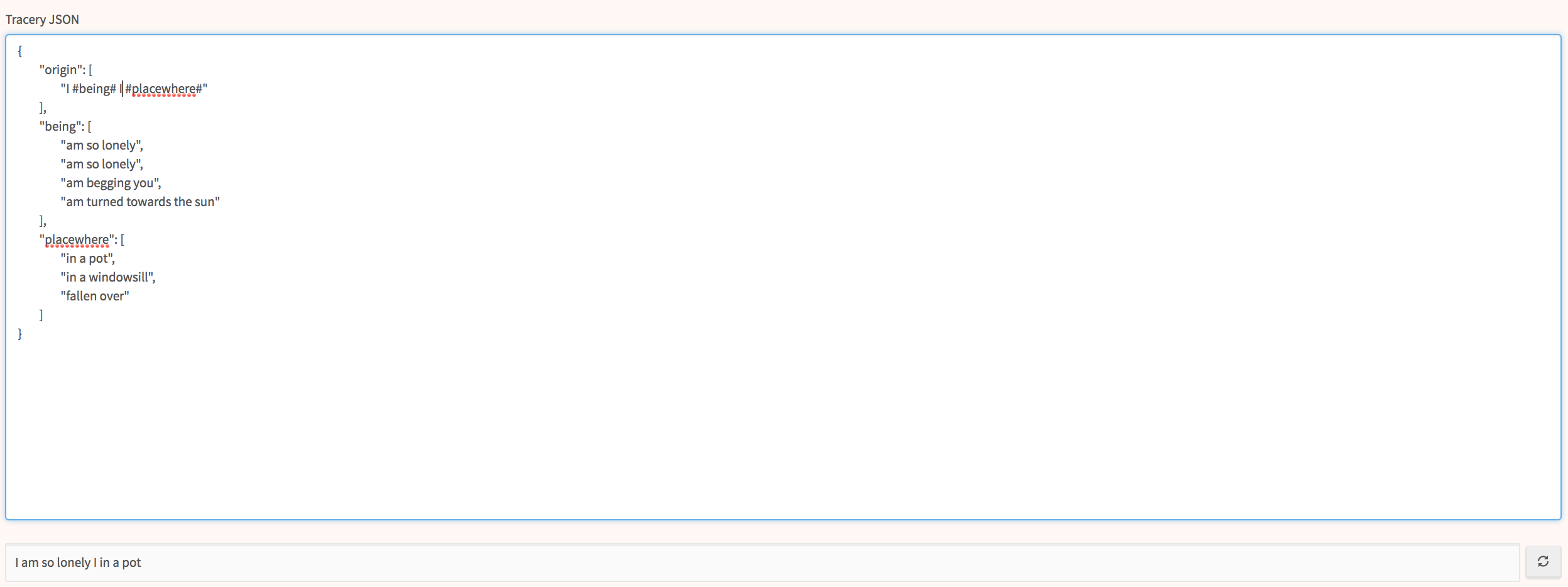

Before we move on, there is one last thing to examine. Press the JSON button in the editor. You should see something like this:

{

"origin": [

"I #being# #placewhere#"

],

"being": [

"am so lonely",

"am so lonely",

"am begging you",

"am turned towards the sun"

],

"placewhere": [

"in a pot",

"in a windowsill",

"fallen over"

]

}

Every Tracery grammar is actually a JSON object consisting of key/value pairs, which is what Tracery calls symbols and rules. (For more on JSON, please see this tutorial by Matthew Lincoln). This is the format we will be using when we actually set our bot up to start tweeting. JSON is finicky. Note how the symbols are wrapped in " as are the rules, but the rules are also listed with commas inside [ and ]. Remember:

{

"symbol": ["rule","rule","rule"],

"anothersymbol": ["rule,","rule","rule"]

}

(of course, the number of symbols and rules is immaterial, but make sure the commas are right!)

It is good practice to copy that JSON to a text editor and save another copy somewhere safe.

But what would a proper ‘historybot’ look like?

Now, re-do the exercise above, but think hard about what a bot for history could look like given the constraints of Tracery. Build a simple grammar to express that idea, and make sure to save it. Here are some other things to think about as you design your grammar:

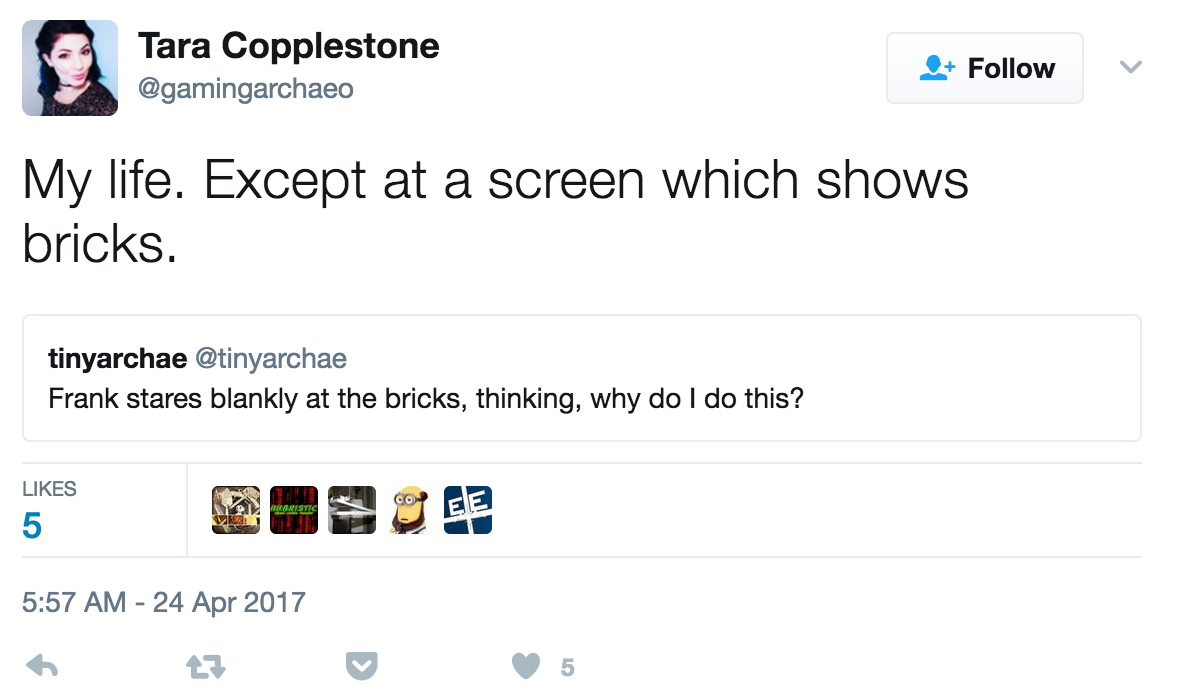

Some of the fun of Twitterbots comes from their serendipitous placement with other tweets in your timeline (you should follow your own bot, just to keep tabs on it):

Maniacallaughbot wins again

Remember that your bot will be appearing in other people’s timelines. The potential for juxtaposition of your bot’s message(s) against other peoples tweets will also influence the relative success of the bot.

An interaction with Tinyarchae prompts wistful reflection

Get a twitter account for your bot and connect it to Cheap Bots Done Quick

You can plumb a bot into your own, current, account, but you probably don’t want a bot tweeting as you or for you. In which case, set up a new Twitter account. When you set up a new Twitter account, Twitter will want an email address. You can use a brand new email address, or, if you have a Gmail account, you can use the +tag trick, ie instead of ‘johndoe’ at gmail, you use johndoe+twitterbot at gmail. Twitter will accept that as a distinct email from your usual email.

Normally, when one is building a Twitterbot, one has to create an app on twitter (at apps.twitter.com), obtain the consumer secret and key, and the access token and key. Then you have to program in authentication so that Twitter knows that the program trying to access the platform is permitted.

Fortunately, we do not have to do that, since George Buckenham created the bot hosting site ‘Cheap Bots Done Quick’. (That website also shows the JSON source grammar for a number of different bots, which can serve as inspiration). Once you’ve created your bot’s Twitter account - and you are logged in to Twitter as the bot account- go to Cheap Bots Done Quick and hit the ‘sign in with Twitter’ button. The site will redirect you to Twitter to approve authorization, and then bring you back to Cheap Bots Done Quick.

The JSON that describes your bot can be written or pasted into the main white box. Take the JSON from the editor and paste it into the main white box. If there are any errors in your JSON, the output box at the bottom will turn red and the site will try to give you an indication of where things have gone wrong. In most cases, this will be because of an errant comma or quotation mark. If you hit the refresh button to the right of the output box (NOT the browser refresh button!), the site will generate new text from your grammar.

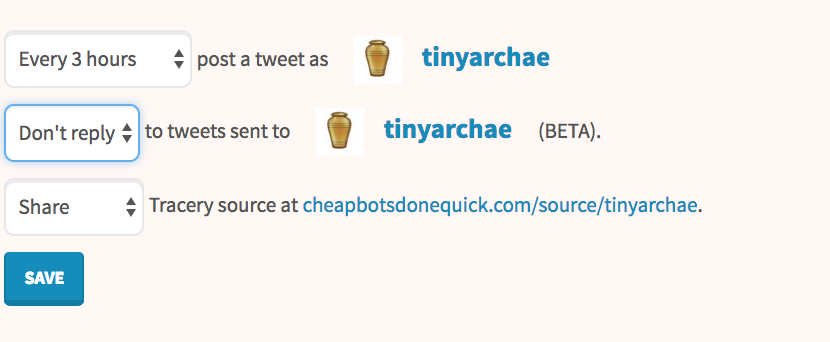

The Cheap Bots Done Quick interface

Underneath the JSON box are some settings governing how often your bot will tweet, whether your source grammar will be visible to others, and whether or not your bot will reply to messages or mentions:

The settings for your bot

Decide how often you want your bot to tweet, and whether you want the source grammar visible. Then… the moment of truth. Hit the ‘tweet’ button, then go check your bot’s twitter feed. Click ‘save’.

Congratulations, you have built a Twitterbot!

Good bot citizenship

As Cheap Bots Done Quick is a service provided by George Buckenham out of a spirit of goodwill, do not use the service to create bots that are offensive or abusive or that otherwise will spoil the service for everyone else. As he writes,

If you create a bot I deem abusive or otherwise unpleasant (for example, @mentioning people who have not consented, posting insults or using slurs) I will take it down

Other pointers for good bot citizenship are provided by Darius Kazemi, one of the great bot artists, are discussed here.

Going further with Tracery

Many bots are a good deal more complicated than what we have described here, but it is enough to get you started. Some surprisingly effective bots can be created using Tracery.

Modifying symbols

Tracery is smart enough to know when a word should take ‘a’ versus ‘an’, and how to pluralize words, or capitalize them. This means that you can provide the base word in a rule, and then add modifiers as appropriate. Consider:

"origin":["#size.capitalize# #creature.s# are nice"]

"size":["small","big","medium"]

"creature":["pig","cow","kangaroo"]

would generate sentences like

Big cows are nice

Small pigs are nice

The modifiers .capitalize and .s are added inside the # of the symbol they are meant to modify. Other modifiers are .ed for past tense, and .a for a/an. There may be more; Tracery is a work in progress.

Use Emoji

Emoji can be used to great effect in Twitterbots. You can copy and paste emoji directly into the Cheap Bots Done Quick editor; each emoji should be within quotation marks as any other rule would be. Use this list to find the emoji you wish to use, and make sure to copy and paste the emoji from the Twitter column to ensure that your emoji will display.

Reusing Generated Symbols with Actions

This feature probably would not be used much in the case of a Twitterbot, but if one was using Tracery to generate a longer story or poem, it can be used so that Tracery remembers the first time it selected a particular rule for a symbol - eg we could get it to always used the same creature every time creature was called subsequently. This is called an ‘action’ by Tracery. The form is #[someAction]someSymbol#. This can be confusing, and this aspect of Tracery is still being developed. To see it in action, copy and past the json below into this Tracery editor by Beau Gunderson: https://beaugunderson.com/tracery-writer/ (select and delete the default text. The Tracery editor we were using earlier does not handle saving data very well, so this alternative is a better tool for our present purposes).

{

"size": [

"small",

"big",

"medium"

],

"creature": [

"pig",

"cow",

"kangaroo"

],

"poem":["My pet #animalfriend# was a very #animalfriendsize# #animalfriend# indeed. My #animalfriend# was named Lucky"],

"origin":["#[animalfriend:#creature#][animalfriendsize:#size#]poem#"]

}

Another, slightly more complex example is example number 5 at Kate Compton’s own tutorial site at https://tracery.io/archival/crystalcodepalace/tracerytut.html:

{

"name": ["Arjun","Yuuma","Darcy","Mia","Chiaki","Izzi","Azra","Lina"]

, "animal": ["unicorn","raven","sparrow","scorpion","coyote","eagle","owl","lizard","zebra","duck","kitten"]

, "mood": ["vexed","indignant","impassioned","wistful","astute","courteous"]

, "story": ["#hero# traveled with her pet #heroPet#. #hero# was never #mood#, for the #heroPet# was always too #mood#."]

, "origin": ["#[hero:#name#][heroPet:#animal#]story#"]

}

Tracery reads the origin, and before it gets to the story symbol it sees an action called hero that it sets from the symbol name. The it does the same for heroPet from animal. With these set it then reads story. Within story the symbol hero reads what was just set by the action, and returns that same value each time. So, if ‘Yuuma’ was selected by the action, then the story will read Yuuma traveled with her pet... Yuuma was never.... If we didn’t set the hero’s name via the action, then the story generated might change the hero’s name in mid story!

Responding to mentions in Cheap Bots Done Quick

Cheap Bots Done Quick has a beta feature that allows your bot to respond to mentions. (Warning: if you create two bots, and one mentions the other, the ensuing ‘conversation’ can run for a very long time indeed; there is a 5% chance in any exchange that the bot won’t respond, thus breaking the conversation).

To set up a response pattern, click at the bottom of the page to set the button to ‘reply to tweets’. In the JSON editing box that appears, you set up the pattern for phrases that your bot will respond to. For instance, some of what @tinyarchae watches for:

{

"hello":"hello there!",

"What|what":"#whatanswer#",

"Who|who":"#whoanswer#",

"When|when":"#whenanswer#",

"Where|where":"#whereanswer#.",

"Why|why":"#whyanswer#",

"How|how":"#howanswer#",

"Should|should|Maybe|maybe|if|If":"#shouldanswer#"

}

The symbols here can include regular expression (Regex) patterns (see this lesson on regular expressions) . So, in the example above, the final symbol is watching for ‘Should’ OR ‘should’ OR ‘Maybe’ OR ‘maybe’ OR ‘if’ OR ‘IF’. To respond to everything thrown its way, the symbol would be the simple dot: .. The rules can include simple text (as in the response to “hello”) or can be another symbol. The rules should be included in your main grammar in the first JSON editing box on the page. Thus, #shouldanswer# is in the main @tinyarchae grammar editor box as a line:

"shouldanswer":["We asked #name#, who wrote 'An Archaeology of #verb.capitalize#'. The answer is #yesno#.","This isn't magic 8 ball, you know.","This is all very meta, isn't it.","#name# says to tell you, '42'."],

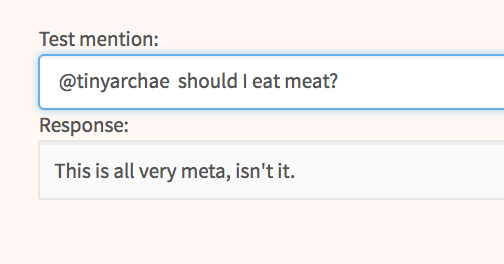

At the very bottom of the page, you can test your mentions by writing a sample tweet that your bot will parse. If you’ve set things up properly, you should see a response. If there is an error, the ‘Response’ box will turn red and will give you some indication of where the error lies.

Testing your bot’s response

SVG graphics

Since SVG is a text format that describes the geometry of a vector graphic, Tracery can be used to create rather artistic work - the Tiny Space Adventure bot draws a starfield, a spaceship, and a plot. Its grammar may be viewed here. The key issue with generating svg with Tracery is to get the components correct. The source code for the softlandscapes bot can be a useful model. This bot begins by defining the critical text that marks out SVG:

"origin2": ["#preface##defs##bg##mountains##clouds##ending#"],

"preface":"{svg <svg xmlns=\"http://www.w3.org/2000/svg\" xmlns:xlink=\"http://www.w3.org/1999/xlink\" height=\"#baseh#\" width=\"#basew#\">"

and then :

"ending":"</svg>}"

Working with SVG can be tricky, as things like backslashes, line endings, quotation marks and so on have to be escaped in order to work properly. As the site tells us,

The syntax looks like this: {svg <svg …> … </svg>}. SVGs will need to specify a width and height attribute. Note that "s within SVG files need to be escaped as \”, as does \#s (\#). {s and }s can be escaped as \\{ and \\}. Note: this feature is still in development, so the tweet button on this page will not work. And the debugging info is better in FF than other browsers.

Bots that generate SVG are beyond the scope of this lesson, but careful study of existing bots should help you on your way.

Music

Strictly speaking, this is no longer about bots, but since music can be notated in text, one can use Tracery to compose music and then use other libraries to convert this notation into Midi files - see http://www.codingblocks.net/videos/generating-music-in-javascript/ and my own experiment.

Other Bot Tutorials

- Zach Whalen How to make a Twitter Bot with Google Spreadsheets

- Casey Bergman, Keeping Up With the Scientific Literature using Twitterbots: The FlyPapers Experiment https://caseybergman.wordpress.com/2014/02/24/keeping-up-with-the-scientific-literature-using-twitterbots-the-flypapers-experiment/ also https://github.com/roblanf/phypapers ; in essence this method collects the RSS feed from journal articles, and then uses a service such as Dlvr.it to push the links to a Twitter account.

- Discontinued: Stefan Bohacek has posted the code templates for a number of different kinds of bots at the code remixing site Glitch.com. If you visit his page, you will see a list of different kinds of bots; click on the ‘remix’ button and then study the readme button carefully. Glitch requires a login via a Github or Facebook account.

- Finally, I would suggest joining the BotMakers Slack group to find more tutorials, like-minded individuals, and further resources: Sign up here

- The Botmakers’ Wiki also has a list of Twitterbot tutorials

Finally, a list of Tracery-powered bots is maintained by Compton here. Have fun! May your bots flummox, entertain, inspire, and confound.

References

Compton, K., Kybartas, B., Mateas, M.: Tracery: An author-focused generative text tool. In: Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Interactive Digital Storytelling. pp. 154–161 (2015)