Contents

- Overview

- Options for Running GPT-2

- Creating our GPT-2 Model

- Using Generated Text as an Interrogative Tool

- Considering the Ethics of Large-Scale Language Models and Generative Text

- Further Readings

- Endnotes

Overview

This lesson is intended to teach you how to apply Generative Pre-trained Transformer 2 (GPT-2), one of the largest existing open-source language models, to a large-scale text corpus in order to produce automatically-written responses to prompts based on the contents of the corpora, aiding in the task of locating the broader themes and trends that emerge from within your body of work. This method of analysis is useful for historical inquiry as it allows for a narrative crafted over years and thousands of texts to be aggregated and condensed, then analyzed through direct inquiry. In essence, it allows you to “talk” to your sources.

To do this, we will use an implementation of GPT-2 that is wrapped in a Python package to simplify the finetuning of an existing machine learning model. Although the code itself in this tutorial is not complex, in the process of learning this method for exploratory data analysis you will gain insight into common machine learning terminology and concepts which can be applied to other branches of machine learning. Beyond just interrogating history, we will also interrogate the ethics of producing this form of research, from its greater impact on the environment to how even one passage from the text generated can be misinterpreted and recontextualized.

Prerequisite Knowledge

For this tutorial, you will need a basic understanding of Python and how to run Python code, whether that be via Jupyter Notebooks or using a text editor and the command line. If you have not used Python before, I suggest going through one of the other Programming Historian lessons designed to introduce you to Python, such as Python Introduction and Installation.

We will be using the Python tool aitextgen to finetune our GPT-2 model. Produced by data scientist Max Woolf, this package was created with a goal of making the training and generation of text-based machine learning models more accessible and democratic for those without the advanced knowledge required to create their own models from scratch. This means that the code we’re writing is quite simple; the greater challenge of this lesson is understanding what the code is doing, which is what you are here to learn.

Introduction to Machine Learning, Language Models, and GPT

Although much of this tutorial will be dedicated to explaining the common terminology used in relation to machine learning, it is beneficial to begin with some base-level explanations to introduce you to the technical terms being used in this lesson.

The term “machine learning” has been mentioned a few times in the lesson already, but what exactly is it? While often thought of as being separate entities, machine learning is actually considered a branch of artificial intelligence concerned with creating computer algorithms that “learn” and thus improve automatically through exposure to data. In this lesson, we are working with language models which take word vectors (in essence, words mapped to and represented by real numbers) and output the estimated probability of the word that will follow. To put simply, machine learning language models look at part of a sentence (i.e., a word) and predict what the following part may be. The most widely-known example of this being Google’s search engine, which predicts your search as you type.

As indicated in the title of this lesson, you are going to use GPT-2 for our experiment with machine learning and language models today. “GPT” stands for Generative Pre-trained Transformer, with the most important part of this initialism being the last word. GPT-2 is a transformer-based language model, which means that it has an attention mechanism that allows for predictions to be made by looking at the entirety of what was inputted to determine each word’s relevance selectively, rather than sequentially by looking at the most recent segment of input as is the case in language models based on recurrent neural networks. The ability of transformer-based models to read all inputted words at once allows for the machine to learn faster, and thus the datasets used for training can be made larger which in turn improves the accuracy of the predictions which the model outputs. Initially developed to advance research in generating text without explicitly labelled training data, GPT’s level of success at this task has allowed it to be utilised for a number of more creative challenges, from being a co-writer for your fantasy novel through platforms such as NovelAI to generating side-quests for adventure games.

Case Study: Brexit in the Media

GPT-2 is a pre-trained model designed to generate unique text based on a given prompt. It already has a vast vocabulary having been trained using a dataset called WebText, which was created by crawling the social media platform Reddit for outbound links and grabbing the text from these web pages. This method resulted in a 40GB dataset which consisted of approximately 8 million web pages, resulting in 1.5 billion parameters (to put simply, words and their weights — the strength of their connections with other words). Through a process known as finetuning, you can harness the power of this model and retrain GPT-2 with your own smaller corpus, resulting in a “specialized” model that now has the vocabulary of your corpus and can produce text on the topic which your corpus discusses.

In this lesson, we will be looking at the phenomenon of Brexit. This portmanteau of “British” and “exit” refers to the referendum held in 2016 to decide whether or not the United Kingdom would remain a member of the European Union (EU), and subsequent related events which occurred following the ultimate decision to withdraw membership. The EU is a political and economic union of nations which aims to reduce barriers surrounding trade and movement across borders through common legal, social, and economic policies. Britain had historically been a part of this union since its foundation in 1993 with the enactment of the Maastricht Treaty. This was the first-ever instance of a member state leaving the EU, and the decision would hugely affect the policies which had previously governed the UK, thus this topic has garnered significant media coverage both nationally and internationally from the year of the referendum up until the point when this lesson is being written in 2022, two years after the UK officially left the EU in 2020. Beyond issues pertaining strictly to politics and economics, the polarising nature of the vote for Brexit brought to light a number of societal issues related to immigration, race, and gender present in Britain. These broader issues were reflected in the publications covering not only the events occurring, but also the perspectives of voters, and the individual actors involved in the referendum and subsequent withdrawal.

Dataset

To interrogate the national narrative generated and disseminated by media coverage regarding Brexit, our input for this lesson will be a dataset of 4036 web-published news articles derived from popular news sources in the UK such as the BBC and The Sun written on the topic of “Brexit”, extracted from the UK Web Archive’s curated “News and Media” collection on this subject. First, the links to each article were gathered so that they could be extracted from their respective webpages in bulk via web scraping through a Python script implementing the Beautiful Soup library. The articles were then exported collectively into a single, large .txt file. The text was then cleaned of any additional HTML tags or unintentionally captured information, such as footer menus, using regular expressions (regex).

For a complete guide on spotting and removing HTML in text downloaded from webpages, you can follow this Programming Historian tutorial which walks you through transforming an extracted webpage into a clean list of words, and for more information on the cleaning with regex, you can view this Programming Historian tutorial on understanding regular expressions. The code used for scraping articles comes from this tutorial that introduces how Beautiful Soup can be used. Although the Beautiful Soup tutorial has been retired due to the underlying website no longer producing the referenced HTML, it is still useful for learning about how the library interprets and interacts with a given web page; should you need more specific guidance on web scraping, there is this tutorial on downloading via Wget, which can be used to download web pages containing articles among other things.

With that being said, should you want to follow along with this lesson using your own data, you must:

1) Ensure that all of the text you would like to feed to your model is in a singular .txt file. If not scraping your data from the web, you may need to convert your files from another format, in which case this tutorial on working with batches of PDFs or this tutorial introducing Pandoc, a command line conversion tool may be helpful.

2) Perform some amount of cleaning so that your output is not hindered by stray stylings as discussed above. GPT-2 does not truly understand what a word is — to a computer, words are just a series of numbers that map to a representation of something that we recognize. This means that a model will train on everything given to it as input, including odd formatting and HTML snippets.

Additionally, another important aspect to consider regarding the data you would like to use with this model, is what language your data is written in. The textual data that was used to train GPT-2 is exclusively in English, thus attempting to use non-English text with this tutorial will likely yield poor results.1 This language barrier is unfortunately common when it comes to text-based machine learning due to greater systemic divides in the field of natural language processing (NLP) and academia broadly; for an in-depth explanation of this topic, see the #BenderRule.

Through training a model on these articles, we can attempt to view this macroscopic narrative —as curated by popular media outlets meant for the average UK citizen to consume— by feeding our model questions about the topic of Brexit. For example, we can ask it about key players or ask it to describe key events, using the prefix functionality of GPT-2. The prefix functionality is a parameter set when asking your model to generate text; it is typically set to a single word which the model uses as a jumping-off point for the text it will produce, but it can also be set to phrases or questions for the generation of more specific text. Essentially, we can set the prefix to something like “Who is BoJo?”, and our model will output a paragraph responding to our query. By “interrogating” our model through its prefix, we can use this “computationally creative” technique to uncover potential trends in the media coverage of this historical turning point, and consider further how this method may be applied to other forms of historical research based on large-scale text-based data.

Options for Running GPT-2

GPT-2, like many other forms of machine learning, requires a significant amount of computing power to run even the “small” version of the model we will use in this tutorial, which still has 124 million parameters (as opposed to the aforementioned 1.5 billion parameters used in the original training of the model). For you to successfully finetune your model without your device freezing up, your computer must have a CUDA-enabled graphics processing unit (GPU) with at least 8GB of VRAM or you may use one of the online services that offer cloud-based GPU computing discussed in a section below.

Machine Learning Hardware 101

If that last sentence left you with many questions, such as “What is a GPU? Why do I need one?” then read this section for a basic introduction to the computer hardware used in machine learning; otherwise, proceed past this to the next section.

The Central Processing Unit (CPU) vs the Graphics Processing Unit (GPU)

Those of you reading this lesson will likely be the most familiar with the term CPU. The CPU is akin to the brain of your computer, accepting a constant stream of information and using its numerous encoded instructions to process and perform both the tasks that you request (e.g., loading a file) and those which keep your computer running (e.g., booting the operating system when you power your device on). A GPU is more akin to a specialized organ like the stomach, as it only has a small number of specific instructions that can be applied to the data it is given. Due to the less general-purpose and more specialized nature of GPUs, they can perform tasks —such as displaying each pixel that makes up the image you see on your screen— very efficiently. In most laptops, the CPU comes with a built-in low-power GPU to handle graphic output; this type of GPU is referred to as an integrated GPU (iGPU), and is not what is used for machine learning purposes. For that, you need a dedicated (or discrete) GPU (dGPU), which is the type of GPU this lesson is referring to when the term is mentioned.

Computer Cores

So why are GPUs —a computer part seemingly meant just for graphics processing— used for machine learning instead of CPUs? The answer to this lies in the “cores” of each component. Both CPUs and GPUs have cores which are where the actual computation happens. Since the CPU has to prioritize the processing of instructions while also performing a variety of operations to complete tasks related to previously given instructions, each core in a CPU must have features like a memory cache to temporarily store data and internal logic that allows all of the instructions it receives to be processed optimally, such as the ability to reorder or reassign tasks to each core as they finish performing a previously assigned task. Due to this necessary complexity, a CPU often only has between two and eight cores in order for your computer to run at a reasonable speed while also keeping CPUs compact and affordable. A GPU core on the other hand does not need all of the specialized features which a CPU core has; a GPU core simply receives the input given to it, performs a singular task, and then provides output. Since GPU cores are much more simplistic in their operations, a single GPU can have hundreds of cores, all capable of processing data simultaneously (formally known as parallelization or parallel computing).

CUDA

If you want to perform a large number of smaller calculations on a significant amount of data —in essence, what machine learning entails— a GPU can do that much faster than a CPU because the processes have more cores to be distributed across, and so more data can be processed at once. When GPUs first began to be used by researchers to speed up scientific computing, the researcher would have to map their problems to a simple graphic output, such as generating a series of triangles, using a graphics programming language which the GPU understood in order to see the results of their experiments.2 This was a very time-consuming endeavour, and ultimately what prompted the creation of CUDA as a solution. CUDA is a parallel computing platform that works with common programming languages such as C and C++, thus eliminating the need for converting problems into a graphics programming language when using a GPU for general-purpose computing and overall simplifying this once-tedious task. This is why most machine learning tasks require a CUDA-enabled GPU, because the software used to create and train models communicates with your GPU through CUDA. Note that CUDA is a proprietary software created by Nvidia, thus in order to use CUDA, you must have a GPU manufactured by Nvidia.

Cloud GPUs

Cloud computing allows for you to access the resources of another computer through the internet; similarly, a cloud GPU allows you to access and use a GPU over the internet. If you do not have a GPU you can use for this lesson, Google offers two accessible cloud GPU services that have a free tier and which function similarly to Jupyter notebooks, using the same .ipynb format:

- Google Colab is perhaps the most well-known of these services. You can enable the usage of a GPU in Colab by creating a new notebook to program in, then going to “Runtime” in the menu and selecting “Change runtime type” > “GPU”. When using this service for free, you can only have a single notebook running for up to 12 hours at a time, which is more than enough for this tutorial.

- Kaggle is an online community dedicated to data science and machine learning. It hosts competitions, courses, and a large number of datasets created for the purpose of training models alongside its notebook functionality. To use Kaggle for this lesson, select the “Code” tab on the home page, and then the “New Notebook” button. In the “Settings” tab located on the notebook page’s sidebar, you can toggle the usage of a GPU under the “Accelerator” label. Kaggle limits GPU usage to 30 hours a week on average, which again is more than adequate for the finetuning being performed in this lesson.

Note that both services are web-based and require you to have an account with the site. To follow this tutorial using either of these services, you can enter each line of code into a cell in your notebook and hit the “Run” button to run the code.

Running Locally

If you have a GPU in your computer that meets the specifications for finetuning GPT-2, then you may follow along with this tutorial using your own device. In order to do so, follow these instructions to prepare your runtime environment:

1) If you do not already have a conda distribution installed on your device (i.e., Anaconda or Miniconda), install Miniconda so that we may create an environment for this lesson and download all dependencies into this environment rather than onto your computer, using the conda package manager.

2) Once Miniconda is installed, open the terminal if you are using macOS or the “Miniconda” prompt if you are on Windows, and create a new environment using the command:

conda create --name prog_hist_gpt2

Then activate the environment with the command:

conda activate prog_hist_gpt2

3) To ensure that your GPU can interact with the CUDA platform correctly, you must first install cuDNN with the command:

conda install -c conda-forge cudnn

Then you must install the CUDA Toolkit with this command:

conda install -c anaconda cudatoolkit

4) Lastly you must install the tensorflow-gpu Python package with the following pip command:

pip3 install tensorflow-gpu

To verify that everything was installed correctly, run the following two commands individually:

python -c "import tensorflow as tf; print(tf.config.experimental.list_physical_devices('GPU'))

python -c "import tensorflow as tf; print(tf.reduce_sum(tf.random.normal([1000, 1000])))

If the first command correctly lists your GPU and the next command runs with no "Could not load dynamic library ..." errors, then you are ready to continue the lesson.

Creating our GPT-2 Model

As you will see, the actual code for this tutorial is quite minimal; when it comes to finetuning a pre-trained model, the power lies in how you modify the parameters.

The last step before we begin training is to install aitextgen, the library we will use for training and generating text via GPT-2. If you are following along with this tutorial using Jupyter Notebook or one of the cloud GPU services covered previously, you will enter and run the following into a new cell:

!pip3 install aitextgen==0.5.2

If you are using your own device, you can enter this same command without the beginning exclamation mark in the command line window that has your conda environment activated. To ensure that this tutorial functions as intended, we are downloading the version of aitextgen that is being used at the time of writing. If you would like to attempt the tutorial using the latest version, then you can remove ==0.5.2 from the end of this command.

After this, we begin the actual Python script! The import statement needed at the top of the script (both for those doing the tutorial locally and those using a cloud GPU service) is:

from aitextgen import aitextgen

Kaggle and Colab both have tensorflow-gpu activated by default, so an import statement for this isn’t necessary; but, if you are writing this script on your own device then you should include the following import statement so that your program recognizes and uses your GPU:

import tensorflow as tf

Next, we have to select and load the GPT-2 model we want to finetune. Do so by adding your next line of code, which states your chosen model and confirms that you want the code to call upon your GPU to run:

ai = aitextgen(tf_gpt2="124M", to_gpu=True)

For this tutorial, as stated previously, we are using the smallest available 124M GPT-2 model to reduce training time and save memory, as the “medium” 355M model and the “large” 774M model will take longer to train and depending on your GPU and the size of your dataset, may be too large to complete training without running out of memory. Since GPU cores do not have a memory cache in the same capacity as a CPU core, the GPU itself comes with VRAM which is used to temporarily store the data needed within the GPU while performing calculations. During the process of training, data is sent in batches to the GPU along with the model and eventually, the growing output; if these combined factors exceed the amount of VRAM available on your GPU, you will get an error that looks like this:

RuntimeError: CUDA out of memory. Tried to allocate 198.00 MiB (GPU 0; 14.76 GiB total capacity; 13.08 GiB already allocated; 189.75 MiB free; 13.11 GiB reserved in total by PyTorch)

In plain language, this error is stating that it needed 198 MB of space to continue training, but there was only 189.75 MB of space available on your GPU and thus training could not continue! To get around this error, you can decrease the batch size (data being sent to your GPU) but more often than not it is a limitation of your hardware which can be fixed by training with a smaller model (assuming you do not wish to reduce the amount of data you are using).

After loading the model, you can now import the text file which contains the data you will be using for training by adding this line:

brexit_articles = "articles.txt"

The data can be downloaded from here in case you did not download it when it was linked earlier in this lesson. If you are using a cloud GPU service, you must upload the file to use it in your program. If you are following along using your own device, you must include this file in the same directory that your script is being run in.

At last, we are now ready to begin retraining GPT-2 with our own data! This is done in a single line of code specifying the hyperparameters:

ai.train(brexit_articles,

num_steps=3000,

generate_every=1000,

save_every=1000,

learning_rate=1e-3,

batch_size=1,

)

In machine learning, a hyperparameter is a parameter set manually prior to training that outlines how the model approaches learning from the data it is given; this is different from the 124 million parameters contained in the GPT-2 model we are using, which are determined through running the training dataset. To expand upon the parameters we use for our code:

num_steps: This refers to the number of “steps” to train the model for. In each step, 1024 tokens from your dataset are passed to the model. To calculate the minimum number of steps your model should have, divide the number of tokens in your dataset by 1024 — this number is the amount of steps needed for all of your data to have been seen at least once by the model. Ideally, though, the number of steps should be higher than this minimum as the model outcomes are best when it sees the same data more than once, allowing for it to gauge improvement.

generate_every: At the interval of steps specified with this hyperparameter, the model will print randomly generated text which can be used to validate improvement over the course of training. Since num_steps is currently set to 3000 and generate_every is 1000, there will be three instances where the model outputs randomly generated text; if you’d like to see how the text your model generates is changing (and, ideally, improving) more frequently than every 1000 steps, you could change this hyperparameter to something like 500.

save_every: When this interval of steps is reached, the model is saved to the /trained_model folder so that if something goes wrong while you are training and the training must halt, you can can continue your training from this lastest save point.

learning_rate: For each step, your model generates a random sample of text and then compares this to the original text; this process is how your model learns! In machine learning, the “learning rate” controls how “big” each of these steps are, determining how significantly the model must be altered in the next step based on how different the generated text is from the original text. The series of calculations behind this are formally known as a gradient descent algorithm, but for this tutorial I will spare you the details of linear algebra and calculus (although here is a more in-depth article should you wish to learn the details) and instead explain the concept behind this algorithm using an analogy to make things more digestible.

Gradient Descent Explained

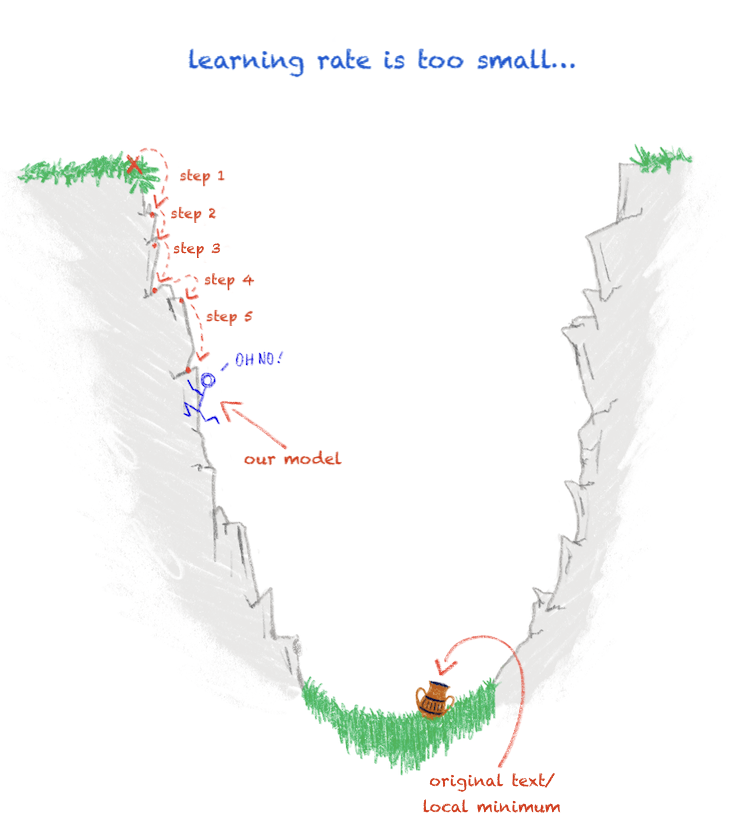

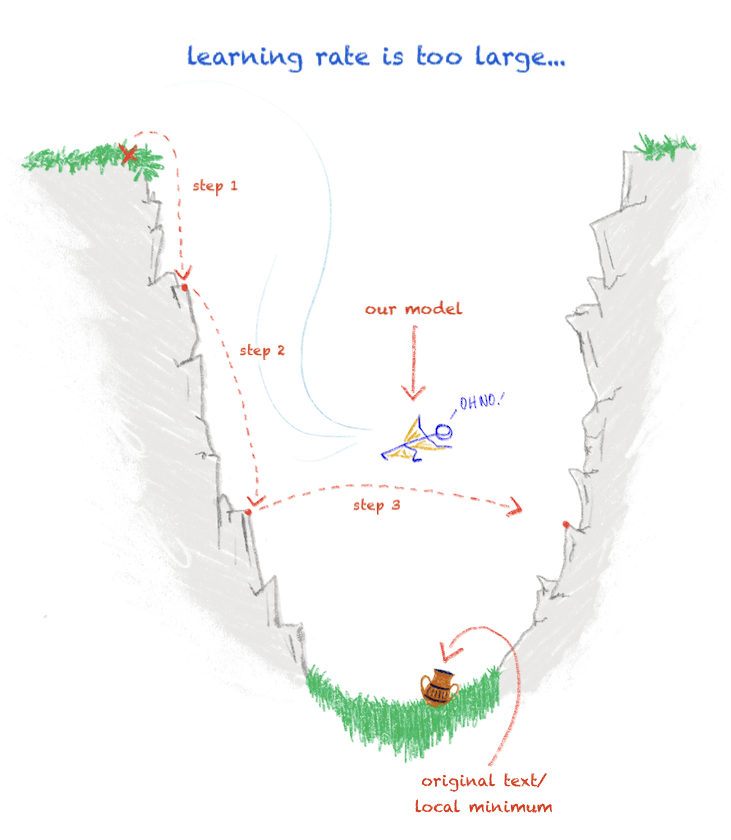

There is an archaeologist working at a dig site, and presently, they are standing on the edge of a trench. In a gradient descent algorithm, this archaeologist represents the starting point (i.e., your untrained model) and the trench is the gradient, a convex function, which must be traversed.

The archaeologist notices a large amphora at the bottom of this deep trench – they must retrieve it! Here, the amphora represents our original text that the generated text is striving to resemble, which is also the global minimum of our gradient. The archaeologist must plan how they will descend into this steep trench in order to retrieve the amphora, and the way they choose to mentally calculate each careful step they take downwards is the learning rate.

While training your model you will see lines outputted that look like so:

[340 | 143.77] loss=0.83 avg=0.72

Here, “loss” is a way to gauge how your model is performing, with the number representing how similar your generated text is to the original text. Much like how the distance between the archaeologist and the amphora decreases as they descend and subsequently get closer to it, as your model trains it should be improving with each step; assuming the learning rate is set correctly, this should result in the loss decreasing.

In an ideal situation, the archaeologist would be able to perfectly calculate each step down the trench towards the amphora, but alas, life is not perfect. If the archaeologist’s steps downward are too small, they may get stuck and become unable to progress further. Similarly, if the archaeologist decides to take drastic measures such as making use of a wingsuit to get to the amphora quickly, their “steps” may be too large and they’ll miss the amphora entirely! Likewise, during training, if the learning rate is set to too small a value then our model will take a very long time to train and may get stuck on a local minimum instead of reaching the global minimum as it should since the model changes so insignificantly from one step to the next (Figure 1). If the learning rate is too large, then the model will train too quickly and overstep the global minimum since it is altered so dramatically at each step (Figure 2).

Visual aid demonstrating a learning rate that is too small

Visual aid demonstrating a learning rate that is too large

There isn’t a straightforward way of choosing the perfect learning rate for your model; it is mostly a process of trial and error. In this tutorial, we are using the standard learning rate of 1e-3 (0.001) since it works for the data given, but should you choose to use your own data the learning rate may have to be changed. If while you’re training you notice the loss decreasing insignificantly or not at all, this means your model is not learning. It is more common for a learning rate to be too large, thus the first correction attempt that should be made is reducing the learning rate (i.e., 1e-3 can be changed to 1e-4).

batch_size: This is the number of batches in which the training set is split during the training loop occurring during each step. For example, if you have a file that has 500 tokens of data and you set the batch_size to five, the data will be divided into 100 batches (500/5) with each batch containing five samples from the data. Batch size is limited by the hardware being used, so by default having one batch reduces the likelihood of an out-of-memory error occurring.

We tune hyperparameters of a model to discover what settings produce the model parameters with the best predictive ability. There are general hyperparameters such as the ones given that work for most datasets, but trial and error through repeat training and adjustments are the only true way to discover the “best” values.

Your model will take at minimum 20 minutes to train depending on the GPU you have, but once this time has passed you should be able to load your model using the line of code:

ai = aitextgen(model_folder="trained_model", to_gpu=True)

This will pull your final model from the trained_model folder and set this as the model you would like to use. Now all that’s left to do is use your model:

ai.generate(n=5,

batch_size=5,

prompt="What is Brexit?",

max_length=250,

temperature=0.7,

top_p=0.9

)

The hyperparameters set here help shape the text generated and can be experimented with to see what yields the most coherent results.

n: This parameter indicates the number of texts you would like to generate at one time in response to your prompt. Set this to “1” and the model will produce only one response to the given prompt, set this to “5” and the model will produce five responses.batch_size: In this case, adding a batch size that matchesnallows for multiple samples to be generated simultaneously, speeding up the generation of text.prompt: This is the key component of this exercise — thepromptis where you can place the question to which you would like your model to respond. If this is phrased as a question, it will attempt to respond, but your prompt may also be given in the form of a phrase that you would like the model to complete and continue (e.g., “Theresa May is…”).max_length: The maximum length is the number of tokens generated in response to your prompt — essentially, the word count. GPT-2 allows for up to 1024 tokens to be generated at one time.temperature: Temperature sets how “crazy” the text generated will be by adjusting how many random completions the model allows while generating the text. At 0.7 the text generated is relatively “normal” while still remaining unique. The highest value of 1.0 results in highly random text, while values below 0.7 up until zero will result in more deterministic text that may simply parrot some of the contents from the original dataset.top_p: Thetop_pvalue generates a set of words related to the prompt where the total probability of these words occurring in association with the words within the prompt is greater than or equal to the value given.

Once complete, your script should look like something like this:

from aitextgen import aitextgen

import tensorflow as tf

ai = aitextgen(tf_gpt2="124M", to_gpu=True)

brexit_articles = "articles.txt"

ai.train(brexit_articles,

num_steps=3000,

generate_every=1000,

save_every=1000,

learning_rate=1e-3,

batch_size=1,

)

ai = aitextgen(model_folder="trained_model", to_gpu=True)

ai.generate(n=5,

batch_size=5,

prompt="What is Brexit?",

max_length=250,

temperature=0.7,

top_p=0.9

)

Using Generated Text as an Interrogative Tool

Why Use Generated Text?

Before we begin to actually generate text, it’s important to pause and establish why we would want to use generated text for research at all. There are many other computational methods of text analysis designed to offer macroscopic insight into a large body of text; you could count word frequencies to find the most common vocabulary used in your text, or you could advance this and use topic modelling to identify topics in your text via clustering words which often appear together. What sets GPT apart from these methods is how the model extracts what is significant based on a specific prompt it is given, and then attempts to create context around what it deems significant through identifying other words most commonly associated with the starting topic. In an experiment with “resurrecting” historical figures through text generation, digital archaeologist Dr Shawn Graham describes this process as “discovering and mapping the full landscape of possibilities.”3 Although this generated context is fictional and often non-sensical, it can still demonstrate how keywords and topics are interacting with each other in the context of your research. In a way, the output of GPT is various interpretations of a singular history being performed, and you are the critic meant to analyze and elucidate each performance. Are these performances completely accurate to their source material? No, but in their “inaccuracy” we can find new perspectives and expositions that differ from our own, which ultimately expands our understanding of the subject at hand.

Keeping this in mind, like with any other method of computational analysis, GPT still requires you to be informed about the concepts you are attempting to analyse, even if the model is informed by more data than even the most prolific researcher could consume and remember. Computational linguist Emily Bender describes human language as being composed of two parts: form, which is the observable realization of language such as marks on a page or bytes in a digital representation of text, and meaning, which is the relation between these linguistic forms and something outside of language 4. We currently do not have the means of expressing the latter component of language, nor is it fully understood, so the input which is given to our language models is merely the form of language, making the output of language models simply form as well. However, this means that our model is unhindered by our burden of reason, with the output it produces being based on statistical probability of connections rather than our less tangible “logic”; thus, as computational linguist Patrick Juola states when discussing the topic of computer-generated text, “even if 99.9% of the possible readings are flat gibberish, the one in a thousand may include interesting and provocative readings that human authors have missed.”5 Our model is producing forms which we may have never considered, yet suddenly, by being presented with these new forms, we can make connections between themes that may have been seemingly unconnected before. We may be the ones prompting the model with questions, but in studying the model’s output, it is prompting us to engage creatively with our research and pushing us to investigate in a way we as historians typically would not.

Interrogating our Model

To begin, we can prompt the model with the basic question of “What is Brexit?” to garner a general idea of the word associations being made by the machine when prompted with the topic of “Brexit”. As indicated by the hyperparameter setting of n=5, I will be asking my model to generate five responses to the prompt and primarily look at the most “convincing” of the responses. While text generated by GPT-2 almost always has some level of coherence, only a small percentage is truly human-like, especially when training using the smaller models; by choosing to generate five samples at a time, I am giving the model five opportunities to produce a comprehensible response to the prompt given from which meaning can be derived.

The two outputs that the model generated which directly responded to this initial question were:

“It is the only way out of the trap.”

“A deal dead on the table.”

The sentiments expressed in these excerpts are rather reflective of the two most prominent themes found in Brexit-related news: the perspective of “Brexiteers” who desired to leave the EU entirely, and those who hoped for some form of a withdrawal agreement despite numerous renegotiations of this deal once the UK had made its decision to withdraw from the EU. The remaining generated text corroborated the findings of a 2018 report on European media coverage of Brexit, which indicated that 35% of coverage discussed the negotiations happening between the UK and the EU, and the most significant topic covered outside of this was Brexit’s impact on the economy, business, and trade, particularly concerning trade over the Irish border.6 For example, instead of defining Brexit as the prompt requested, one response instead began with defining the Irish backstop:

“The backstop is an insurance policy designed to prevent a hard border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland and preserve the Good Friday Agreement.”

In the responses to this prompt, there was one segment that did seem unexpected and fell outside of the repeat outputs related to economics and trade:

“But if you can see the European Union, you can see the British people who are not only themselves as being ignorant racists. There is a lot of evidence that this is the case. There are some things that are that are deeply saddening about the UK’s attitude to Brexit.”

The grammar of this response is somewhat odd, but what this statement being generated indicates is that there is a branching association with the discussion of the UK and racism. With the EU allowing free movement across borders, the topic of immigration was common in deliberations over Brexit’s potential impact. For those campaigning to leave the EU, narratives surrounding the open border’s allowance of refugees impacting the safety of English citizens were popular, and these narratives focused on Muslim individuals in particular.7 This generated response is likely reflecting the public response to those narratives that were present in media coverage based on citizens’ opinions.

Beyond asking your model to answer prompts, you can also ask it to complete a statement. For this next point of analysis, I will ask my model to complete a prompt regarding the two prime ministers who oversaw the UK following its vote to withdraw from the EU: Theresa May and Boris Johnson. To begin, I will set the prompt to “Theresa May is”.

Immediately, we are met with a comical example of accidental sexism as the model writes:

“Theresa May is a long-term thorn in the UK, and has a record of making decisions.”

As if PM Theresa May is a thorn in the UK’s side, for the dreaded crime of decision making! While it is unlikely that May was criticised simply for making decisions, output such as this could reflect a level of harshness in the media’s coverage of the numerous decisions and negotiations she performed during her time as prime minister.

When considering covert forms of sexism that are more likely to be found in modern media, a more insightful response to this prompt was the following:

“Theresa May is a headmistress of the political process. She has a record of her own party and a history of fierce struggle and fierce dedication to the right-wing Leavers.”

In a comparative analysis of the media coverage of former female prime ministers Margaret Thatcher and Theresa May, political scientist Blair Williams posits that both women were framed using stereotypically feminine norms in news coverage, with a popular strategy to do so being the comparison of these leaders to schoolgirls or headmistresses to emphasise their femininity.8 Our model seemingly picks up on this discourse, and as was common in the coverage of May in the media, states that she is the fierce “headmistress of the political process”, removing her from the prime ministerial role she actually occupied and instead returning her to one of the positions of leadership that women can acceptably occupy in a patriarchal society.

Outside of the term “headmistress”, other terms the model used to describe May —such as “fierce”, “passionate”, and “bold”— take on a similarly gendered nature when contrasted with the generated text completing the phrase “Boris Johnson is”:

“Boris Johnson is a ‘realistic leader of the right wing of the House of Commons who has put clear ground between him and the rest of the House of Commons’.”

“Boris Johnson is a long-term, highly skilled, moderate and dynamic politician who has the skills to make sure that the UK is ready for a hard Brexit, and with the EU too, he has the faintest idea what a no-deal scenario will happen at this juncture.”

In a 2019 article looking at the role of masculinity in Brexit campaigning and negotiations, it has been theorised that toxic masculinity manifested itself through the usage of both language associated with militarism and language associated with deal-making and business rhetoric.9 Militarism valorises traits historically associated with masculinity: heterosexuality, strength, power, autonomy, resilience, and competence. Adding to these traditional perspectives, the masculinised spaces of corporate business idealise competitive individualism, reason and self-control.10 In describing Johnson as a “realistic leader” and “long-term, highly skilled, moderate and dynamic politician”, our model confirms this notion of favouritism towards masculised leadership that delegitimises feminine traits, especially when contrasted with the more emotional language used to describe May.

While our finetuned GPT-2 model does not always respond exactly as expected based on the prompt you have given it, from just these three prompts the paths of meaning that it does generate can map out the macroscopic themes present in a body of work, providing guidance for more in-depth microscopic analysis. What makes a generated text interesting for historical inquiry is not necessarily just how coherent the outputted text is, but its ability to create patterns from the inputted text that we as humans may be incapable of detecting ourselves. As exemplified in this analysis, when studying the generated text, make note of the points which reoccur in responses generated for the same prompt— why might the model be repeating these points? In contrast, there can also be value in asking, “what ideologies resulted in the formation of this?” when a particularly outlandish response is generated, with its difference from the other responses perhaps pointing towards a niche yet still present view within your corpus. I encourage you to experiment beyond these three examples, and when looking at the responses generated by your model, seek to understand how exactly the connections your model has made may have come to be in order to seek a possible source.

Considering the Ethics of Large-Scale Language Models and Generative Text

At this point in the lesson, you have learned what language models are and how they work, about the computer hardware and technologies necessary to use them, and how to create a model of your own by finetuning an existing model with your own data. While using this model is a creative way to aggregate the concepts present in a large corpus and gain a macroscopic perspective on its most prevalent topics, no technology is without limitations.

In this lesson, we are analyzing a very recent history, and our dataset is composed of many articles that were present during the creation of GPT-2. When WebText was being created, Brexit was a popular topic of discussion on all social media platforms including Reddit, meaning that even prior to finetuning GPT-2 with our data, Brexit was highly represented in the original training data.11 Yet, despite our topic being highly represented in WebText, it is important to consider what other factors went into the creation of this dataset that could be affecting the results which GPT-2 models output. In a post discussing GPT-2 and its provenance by the group of individuals who developed this technology (OpenAI), they describe in a footnote the creation of WebText as follows:

“We created a new dataset which emphasizes diversity of content, by scraping content from the Internet. In order to preserve document quality, we used only pages which have been curated/filtered by humans — specifically, we used outbound links from Reddit which received at least 3 karma.”

From this quote, it seems that OpenAI is equating diversity of data with quanitity of data, which is not necessarily accurate, especially when the data is curated from one source. In a study done by the Pew Research Center in 2016 (the same year that WebText was created) 67% of Reddit users identified as male, and 64% of these users were between the ages of 18 to 29; further, 70% of this user base fell into the category of “white non-Hispanic”.12 This indicates that a majority of the links used to create the dataset were curated by those who fell into this demographic. Narrowing things even more, as mentioned earlier in this tutorial, any non-English language text was deliberately removed from the dataset prior to training the original GPT-2 model, meaning that WebText is largely made up of what interests English-speaking, young, white men — not very representative of diverse content or opinions.13

There is also a more insidious element to massive, automatically generated datasets like WebText, as their scale makes it difficult to entirely know their contents. A study dedicated to evaluating the contents of WebText and its open-source replication OpenWebText Corpus uncovered that at least 12% (272,000) of the news sites referenced in the creation of these datasets came from sources of low or mixed reliability; in addition to this, 63,000 of the links came from subreddits that had been quarantined or have since been outright banned from the site.14

The static nature of training data can also be a potential source of harm; much has happened in our world since the provenance of WebText, and, as stated in the article “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?” by Emily Bender, Angelina McMillan-Major, and Timnit Gebru, “a central aspect of social movement formation involves using language strategically to destabilize dominant narratives and call attention to underrepresented social perspectives. Social movements produce new norms, language, and ways of communicating.”15 With a base that remains stagnant in 2016, GPT-2 and many other large-scale language models that would be costly to retrain lack consciousness of the language formed and used in current society, resulting in generated text that may reflect a previous, less inclusive world view.

With that being said, there have been efforts to combat these issues unearthed by the release of GPT-2, the most prominent being the text generation models developed by OpenAI’s open-source competitor, EleutherAI. This organization was founded in 2020 with the goal of replicating and improving upon OpenAI’s closed-source and paid-for successor of GPT-2, GPT-3, which had just been released. EleutherAI’s efforts resulted in the creation of GPT-Neo, a large scale language model that, although smaller than GPT-3, was as equally powerful in performance when compared with GPT-3’s smaller models. One of the elements that made GPT-Neo distinct from the original GPT-3 was that it was trained on a dataset EleutherAI compiled called the Pile which, while still static in nature, was designed to address some of the aforementioned problems of diversity in data through incorporating sources outside of Reddit —such as academic journals, Wikipedia, and other web-based forums— and attempted to more effectively and transparently document this dataset’s contents through the creation and publication of a datasheet.16 The open-source approach taken by EleutherAI when producing this model combined with its enhanced performance over GPT-2 resulted in it being a popular choice for use by individuals who wanted to experiment with generative text; in fact, if you took a look at the aitextgen documentation earlier, you may have noticed that you can choose to use GPT-Neo instead of GPT-2 for finetuning. This tutorial uses GPT-2 because even the smallest GPT-Neo model is still slightly larger than then GPT-2’s smallest model, thus it needs slightly more powerful hardware to train; if you do have an adequate GPU, to finetune with GPT-Neo, change the line ai = aitextgen(tf_gpt2="124M", to_gpu=True) of your code to instead use ai = aitextgen(model="EleutherAI/gpt-neo-125M", to_gpu=True).

As the size of our models grow, our understanding of the training data is not the only thing that becomes more difficult to grapple with; regardless of how diverse or well-documented the training data is, there remains an environmental impact that should be considered when working with machine learning technologies that require a GPU. The GPUs required for the creation of models like GPT-2 are incredibly power-hungry pieces of hardware; in 2019, it was found that the training of a single large transformer model emitted more CO2 than the lifetime use of a car driven daily.17 While the hyperparameter tuning done with a small dataset as demonstrated in this lesson has very minimal impact, considering it is estimated that we must cut carbon emissions by half over the next decade to deter escalating rates of natural disaster, should you wish to perform this kind of analysis using a much larger dataset, it is important to consider the ways you can minimize your carbon footprint while doing so; for example, choosing to use a cloud GPU service rather than purchasing your own GPU to run at home (unless of course, your home relies on a sustainable source of energy).

In their totality, all of these considerations have particular implications for a programming historian. GPT-2 has significant potential for abuse — so much so that even the documentation for aitextgen has a page discussing ethical usage of this tool. As you read through your model’s output, you may have felt that while the text was impressive, it did not seem quite good enough to have been believably written by a human; but, you may have felt this way because you were conscious of the fact that what you were looking at was computer generated. Did you notice how the model, in an effort to produce “convincing” news-like output, would create and attribute quotes to various actors involved in Brexit negotiations? What might happen should one of these quotations be removed from the context of generative text and be referenced as something the person to which the quote was randomly attributed had actually said? At best, a situation like this would contribute to spreading misinformation, but at worst, the quote could be something that reflected the more offensive content of WebText resulting in a person receiving unjust slander.

Lastly, on a more academic note, should you decide to use GPT-2 to interrogate a historical dataset, you must ensure that your analysis accounts for the underlying training data of GPT-2 being from 2016. Although you are inflecting the language model with your own historical source, the original dataset will still influence how connections between words are being made at the algorithmic level. This may cause misinterpretation of certain vocabulary that has changed in meaning over time should your dataset not be large enough for your model to learn the new context in which this word is situated— a concern that is consistently present in all forms of language-based machine learning when applied to historical documents.18 As a whole, the use of GPT-2 for historical applications offers a unique (and often humourous) alternative to more traditional methods of macroscopic text analysis to discern broader narratives present in large text-based corpora. Yet this form of research is also an example of how the very technology you are using can influence the outcome of what you produce. It is important to be conscious of how the tools you use to study history can impact not only your own work, but also the world around you.

Further Readings

The use of generated text as an analytical tool is relatively novel, as is the application of AI and machine learning to humanities work broadly. As these technologies continue to rapidly advance, so does the research related to the ethics of their use and applications. While this lesson was in the process of peer-review, Dædalus, a multidisciplinary journal published by the American Academy of Arts & Sciences, released their Spring 2022 issue titled “AI & Society” which grapples extensively with topics discussed throughout this lesson. I would recommend the entire issue for further reading, but articles of particular relevance to this lesson are:

-

Choi, Yejin. “The Curious Case of Commonsense Intelligence.” Dædalus 151, no. 2 (Spring 2022): 139-155. https://www.amacad.org/publication/curious-case-commonsense-intelligence.

-

Rees, Tobias. “Non-Human Words: On GPT-3 as a Philosophical Laboratory.” Dædalus 151, no. 2 (Spring 2022): 168-182. https://www.amacad.org/publication/non-human-words-gpt-3-philosophical-laboratory.

-

Agüera y Arcas, Blaise. “Do Large Language Models Understand Us?” Dædalus 151, no. 2 (Spring 2022): 183-197. https://www.amacad.org/publication/do-large-language-models-understand-us.

Endnotes

-

Jeffrey Wu et al., “Language Models Are Unsupervised Multitask Learners,” OpenAI, (February 2019): 7, https://cdn.openai.com/better-language-models/language_models_are_unsupervised_multitask_learners.pdf. ↩

-

David Tarditi, Sidd Puri, and Jose Oglesby, “Accelerator: Using data parallelism to program GPUs for general-purpose uses,” Operating Systems Review 40, (2006): 325-326. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/tr-2005-184.pdf. ↩

-

Shawn Graham, An Enchantment of Digital Archaeology: Raising the Dead with Agent-Based Models, Archaeogaming, and Artificial Intelligence (New York: Berghahn Books, 2020), 118. ↩

-

Emily M. Bender and Alexander Koller, “Climbing towards NLU: On Meaning, Form, and Understanding in the Age of Data,” (paper presented at Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Online, July 5 2020): 5187. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2020.acl-main.463. ↩

-

Kari Kraus, “Conjectural Criticism: Computing Past and Future Texts,” Digital Humanities Quarterly 3, no. 4 (2009). http://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/3/4/000069/000069.html. ↩

-

Alexandra Borchardt, Felix M. Simon, and Diego Bironzo, Interested but not Engaged: How Europe’s Media Cover Brexit, (Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, 2018), 23, https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2018-06/How%20Europe%27s%20Media%20Cover%20Brexit.pdf. ↩

-

Satnam Virdee & Brendan McGeever, “Racism, Crisis, Brexit,” Ethnic and Racial Studies 40, no. 10 (July 2017): 1807, https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2017.1361544. ↩

-

Blair E Williams, “A Tale of Two Women: A Comparative Gendered Media Analysis of UK Prime Ministers Margaret Thatcher and Theresa May”, Parliamentary Affairs 74, no. 2 (April 2021): 408, https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsaa008. ↩

-

Columba Achilleos-Sarll and Benjamin Martill, “Toxic Masculinity: Militarism, Deal-Making and the Performance of Brexit” in Gender and Queer Perspectives on Brexit (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), 23, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03122-0_2. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Alec Radford et al., “Better Language Models and Their Implications,” OpenAI (blog), February 14, 2019, https://openai.com/blog/better-language-models/. ↩

-

Michael Barthel et al., Seven-in-Ten Reddit Users Get News on the Site, (Washington: Pew Research Center, 2016), https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2016/02/25/reddit-news-users-more-likely-to-be-male-young-and-digital-in-their-news-preferences/ ↩

-

Jeffrey Wu et al., 7. ↩

-

Samuel Gehman et al., “RealToxicityPrompts: Evaluating Neural Toxic Degeneration in Language Models,” Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics (January 2020): 3362, https://aclanthology.org/2020.findings-emnlp.301.pdf. ↩

-

Emily M. Bender, Timnit Gebru, Angelina McMillan-Major, and Shmargaret Shmitchell, “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big? 🦜,” ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (March 2021): 614, https://doi.org/10.1145/3442188.3445922. ↩

-

Biderman, Stella, Kieran Bicheno, and Leo Gao, “Datasheet for the Pile.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2201.07311 (2022) ↩

-

Emma Strubell, Ananya Ganesh, and Andrew McCallum, “Energy and Policy Considerations for Deep Learning in NLP,” Association for Computational Linguistics (June 2019): 1, https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1906.02243. ↩

-

Maud Ehrmann et al., “Named Entity Recognition and Classification on Historical Documents: A Survey,” (Preprint, submitted in 2021): 12-13. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2109.11406. ↩