Contents

- Introduction

- Required Materials

- Why Games?

- Scaffolding Game Creation

- Creating a Twine Game

- What’s Next?

- Endnotes

Introduction

Playing and making games in the classroom, offers us a powerful opportunity to critique cultural narratives and create new narratives of our own. Games are an increasingly important part of our cultural landscape. In 2020, the global gaming industry generated an estimated income of over 77 billion dollars. The Entertainment Software Association estimates that approximately 65% of American adults play some form of video-game.

Increasingly, students and the general public are engaging with history, politics, and social issues through games. For example, 2020’s bestselling Red Dead Redemption II (over 22 million copies sold) is set in the U.S. in 1899 and alludes to the American Civil War, industrialization, and the forced relocation of Indigenous peoples. As Krijn Boom, et al. note, game companies are “keen to make use of a variety of historical pasts as this provides them with recognizable themes, settings or narrative frameworks.”1 However, games do not always represent the past (or the present) in an accurate or thoughtful ways.

This lesson starts with a brief overview of games and game studies, then moves into practical suggestions for incorporating text-based games in the classroom. I then provide a technical tutorial for making a text-based game using the open source game creation platform Twine. Twine offers an accessible way for students and scholars to make text-based games. As part of the technical tutorial, you will learn how to create a text-based game with six sections. You will learn how to incorporate choices, code (macros), and styling into your game. The lesson ends with sample Twine assignments and additional resources. The lesson assumes no prior knowledge of games/gaming and no prior technical skills.

In this lesson you will learn:

- Basic strategies for incorporating games into teaching and research

- How to create a simple text-based game using the free, open source platform Twine

- How to add complexity to a Twine game using code (macros) and CSS styling

Required Materials

To follow along with this lesson, you will need a computer with an internet connection to access Twine. Twine can be downloaded and run on your desktop, but it can also be run directly in the browser. I use Twine version 2.3.12 (the current version of Twine available in the browser as of 2/11/21). I provide instructions for using Twine directly in the browser. The advantage of using Twine directly in the browser is accessibility. The disadvantage is that you will need to download and save your game to your desktop, then upload it to the browser again each time you begin a new working session. This is because the browser-based version of Twine only stores your game in the browser’s cache. I discuss the steps for saving your game in more detail in the section titled “Saving Your Game”.

When using Twine in the browser, you may want to avoid certain versions of Internet Explorer and Safari. My students have reported issues saving their games in both Internet Explorer and Safari. Chrome, Firefox, and Opera are fully supported.

One potentially confusing aspect of Twine is that the platform allows you to work with several story formats, or visual layouts. The syntax for each story format works a little differently. The examples I use are written for the default format, Harlowe 3.2. To follow along with this lesson, you will not have to modify the story format. When looking for answers to your Twine questions on the web, make sure you include the story format in your query: e.g., “how to change background color in Twine Harlowe 3.2”.

To teach Twine in the classroom, your students will also need access to computers with internet connections. It is possible to use Twine on a mobile device, but the interface is challenging. I have taught Twine in classes where not all of my students had access to computers by having 2-4 students share a computer and create a game as a group.

Why Games?

The academic study of video-games has existed since the 1980s, with scholars from multiple disciplines, including English, History, Psychology, and Education, analyzing games as cultural artifacts. Humanities scholars draw on a number of tools and lenses to study games, borrowing from film studies, feminist analysis, queer theory, and digital rhetoric. In recent years, the field of Game Studies has gained traction as the video-game industry has grown. Mainstream and independent games often deal directly with literary source material (Walden), historical settings (Assassin’s Creed) or socio-political issues (Papers Please). For examples of game scholarship from multiple fields, see the journal Game Studies.

Creating Games

In addition to writing about games, humanities scholars are increasingly making games as a form of scholarship. Though every medium comes with advantages and disadvantages, games are particularly suited for:

- Creating accessible, wide reaching public humanities scholarship

- Facilitating communal play and communal learning

- Modeling complex systems, or the relationship between options and outcomes

For example, Wendi Sierra’s NEH funded collaborative project A Strong Fire uses narrative and vocabulary games to educate players about Oneida language and cultural values. The game is a collaboration between scholars in English and Game Studies, as well as artists, musicians, and tribal members. A Strong Fire is geared toward elementary-aged children and their parents and is intended to foster intergenerational and communal play. A Strong Fire demonstrates the way that games as a medium can offer scholars the opportunity to create an accessible and wide-reaching public platform that fills gaps in the cultural record.

Scholars are also using games to make rhetorical arguments. As Stephen Ramsay and James Coltrain note, “games are defined by formal or informal rules, and these rules can be adapted to reflect similarly structured humanistic arguments.”2 Sometimes these humanistic arguments are historical; William Urrichio notes that, “we might think of the rule systems that characterize various brands of history as constituting the potential rule systems for game play” (336).3 A game’s argument may be intended to spark social change; Cait Kirby’s Twine game September 7th, 2020 allows the player to experience the first day of returning to in-person classes during the 2020 coronavirus pandemic from multiple perspectives, including an immuno-compromised college sophomore and an assistant professor. Players are confronted with complex choices that often result in equally negative outcomes, such as “Do you motion for the student to put their mask on or pull your own mask tighter?” September 7th, 2020 argues that the decisions made by university administrators have resulted in unfair choices for students, faculty, and staff. This argument has been successfully made in many different mediums. However, putting the player in the position of making these choices lends an emotional immediacy to the appeal.4

Teaching Games

Perhaps because of an increase in games as scholarship, games have also enjoyed increased usage in the classroom. While some instructors use games as educational tools (e.g., to teach vocabulary) others use games as texts, asking students to analyze the rhetorical messages embedded in commercial games. There are several advantages of coupling game analysis with game creation:

- Asking students to create cultural artifacts encourages them to think critically about the design choices that inform the popular media they consume

- When students are tasked with creating a game, they must think carefully about audience and rhetorical choice

- Encouraging students to create games can be empowering. Popular games are filled with historical misconceptions, poor representation, and repetitive narratives By creating their own games students can begin to imagine and execute the types of change they would like to see in popular media

- As a secondary benefit, game creation can be a good way to expose students to computational skills and careers that they may have otherwise thought were out of reach

One of the greatest challenges of teaching games as texts, is the accessibility of games and gaming systems. Text-based games, or interactive fiction, are a relatively accessible medium to work with. There are multiple platforms for creating interactive fiction.5 These games can be played directly in the browser and are often free to play. While text-based games and interactive fiction enjoyed mainstream success in the 1970s-80s, Twine games have enjoyed recent popularity among independent creators, queer developers, and activists. Most interactive fiction games do not require speed, dexterity, or previously learned gaming “skills.” This is significant, since many students (especially women) may not identify as gamers.6

It is also important to take accessibility and confidence levels into account when teaching game creation. According to the Computer Science Teacher’s Association, women and students of color are less likely to have received computer science training in middle school or high school. This, combined with harmful cultural stereotypes, can result in low programming confidence levels. As a platform, Twine has several advantages: scholars and students with no programming experience can create their first Twine game within minutes of opening the platform. As Janet Davis notes, instructors can encourage women and minority students to engage with computer-science-related skills by portraying computing as “a tool for solving problems that matter.”7 The popularization of accessible platforms like Twine has resulted in independent games that reflect perspectives often ignored by the mainstream industry. LGBTQ+ creators (including Porpentive and Anna Anthropy) have been a key part of this movement. In “Rise of the Videogame Zinesters,” Anna Anthropy argues that Twine and similar platforms have decentralized creative power. Twine allows students to use programming to create personalized stories and develop meaningful arguments.

Scaffolding Game Creation

It is important to scaffold game creation in order to create as even a playing field as possible for students, who will come into the classroom with radically different experiences with and expectations about playing games, and with varying levels of digital literacy. Collectively playing a game, analyzing a game, and discussing cultural and historical context is a good way to scaffold game creation.

Myth Busting

An important first step in creating a meaningful and inclusive environment for game creation is addressing common misconceptions. Students often start my classes believing that:

- Games are purely for entertainment and are ideologically “neutral”

- Certain types of games are more legitimate than others

- Only certain types of people play games (students may feel that the games they play, such as mobile games, do not qualify as “real” games)

- That games easily create social change by automatically sparking empathy

Playing and analyzing a game is a helpful way to challenge these assumptions. Games with strong rhetorical arguments are a good place to start. I begin many of my game units with Zoe Quinn’s Twine game Depression Quest, in which you play as someone living with depression.

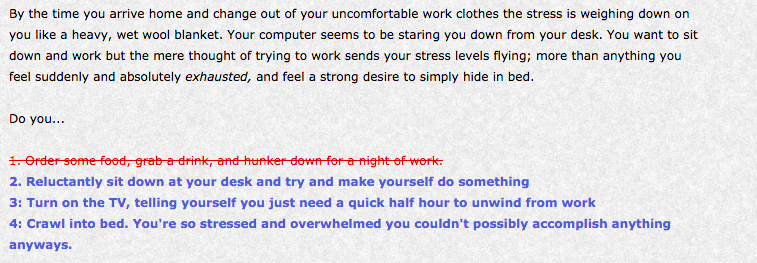

Figure 1. Example from Depression Quest

The game aims to help people understand the depths of mental illness. While the game treats depression respectfully, students should be provided with a content warning. Students often react to this game by noting that: they did not realize games could be about serious topics, they did not realize a game could make an argument, and they did not realize a game could be a story.

Analyzing a Game

I find it helpful to lead in-class game analysis with a series of questions that draw attention to the rhetorical nature of games:

- What is the game’s argument?

- What design decisions (at the level of both narrative and mechanics) contribute to this argument?

- Who is the intended audience? What design decisions were made to engage this audience?

- What is the relationship between you, the player, and the player character (the character controlled by the player)?

For example, in Depression Quest, the player character’s mother pressures the player character to stop “sitting around feeling sad.” The game’s mechanics, or the rules that govern gameplay, push against this attitude—the player is presented with seemingly positive options (as is shown in Figure 1.) some of which they cannot choose. The story and mechanics work together to argue against the harmful misconception that those suffering from depression can simply choose to stop feeling sad. This suggests that the game is geared towards players who might be in support roles for a friend or family member living with depression. It is also important to question the degree to which the game creates empathy: by playing Depression Quest, does the player know what it is like to live with depression? While the game might cause the player to feel emotion for a given character, this does not mean that the player can fully understand another positionality or that the player will act differently after playing the game. Games can emotionally move us, but they do not necessarily change our actions.

Introducing Context

It is difficult to talk about games without talking about issues of representation. While students may not be directly familiar with the ways these issues shape the gaming industry, many will be familiar with implicit arguments and stereotypes: “women don’t play real games,” “the hero is usually a white guy.”

The specific pieces of cultural and historical context you might use to frame this discussion depend on the nature of the class and the games you are playing/making. I often teach games in Women and Gender Studies classes. I find it helpful to discuss the “Gamergate” controversy of 2014, an online harassment campaign directed against women in the gaming industry (Zoe Quinn, the creator of Depression Quest, was the initial target). Gamergate is primarily useful for discussing the biases that pervade the gaming industry, however, it can also facilitate a conversation about the potential repercussions of publishing games. I never require my students to distribute or host their games publicly. I also do not require them to share their games with classmates (although I encourage them to do so). Instructors should consider the potential consequences of asking students to share their games, especially given the internet backlash against women, queer folks, and people of color.

I also find it useful to raise questions about how games are made. Since Gamergate, studios have received increased pushback for a lack of diversity in representation. In some cases, this has resulted in more diverse representation but not better representation. For example, Red Dead Redemption II faced criticism for its depiction of Charles, a Black and indigenous character. Part of the critique stemmed from the fact that a non-indigenous, non-black actor was cast to voice Charles. This type of example raises productive questions for classroom discussion:

- Who gets to make games and why?

- What does it mean to represent the past “accurately”?

- Who gets to tell another person’s story?

Ideally, engaging these questions foregrounds several realizations about creating historical and cultural narratives:

- It is important to think critically about our own positionality and how it informs the narratives we create

- It is important to understand the ways in which narratives are partial, subjective, and constructed

- It is important to directly engage with the perspectives we are trying to represent (e.g., through community partnership)

Drawing from other forms of public, historical storytelling can also be helpful. The issues of ethics and representation raised by game creation are also raised by historical archives and history harvests, both of which grapple with what it means to tell other people’s stories publicly.

Drawing on theoretical approaches to game studies can also provide useful context. Feminist Game Studies and Queer Game Studies offer useful frameworks for talking not only about representation, but about the ways in which different types of play (e.g., competitive play versus communal play) can bolster and subvert cultural values. I also find it helpful to introduce students to the concept of procedural rhetoric, the idea that mechanics are as rhetorical and persuasive as narrative.

Creating a Twine Game

After you and your students have become familiar with some of the conventions and contexts surrounding text-based games, you are ready to make your first game.

In what follows I walk through creating a simple Twine game with six sections, or “passages,” called “First Day in the Office.” I start by creating the game, then add complexity using “macros,” or code, and finally add styling. The game is inspired by many of the games my students have created in Intro to Women’s Writing. Over the course of the semester, we read and discuss authors’ and artists’ arguments about gender (ranging from Mina Loy’s Feminist Manifesto to Sylvia Plath’s contemplation of work/life balance in The Bell Jar). For the game assignment, I invite students to weigh in on the conversation by creating a game that expresses an argument they would like to make about gender and/or sexuality.

In the game I walk through below, the player character will move through her first day of a summer internship with a tech company. The game deals with several of the themes my students choose to write about, including workplace discrimination and the fatigue that comes from being a minority in the workplace. I have included a more fleshed out version of this game, with additional sections and examples of Twine functionality, in the resources section.

You can create a successful Twine game using limited technical elements. However, there are some basics of game design that can turn a technically simple game into a narratively complex game. The game we will make is technically straightforward–it involves narrative and basic, text-based choices that the player can make. However, we will work to create choices that connect to the game’s rhetorical goals.

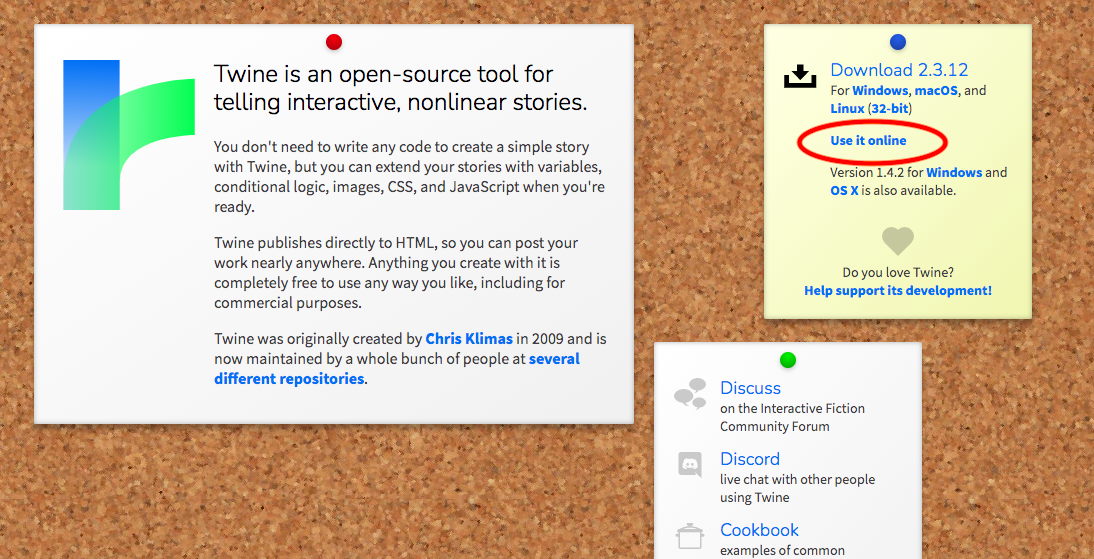

Creating Your First Story

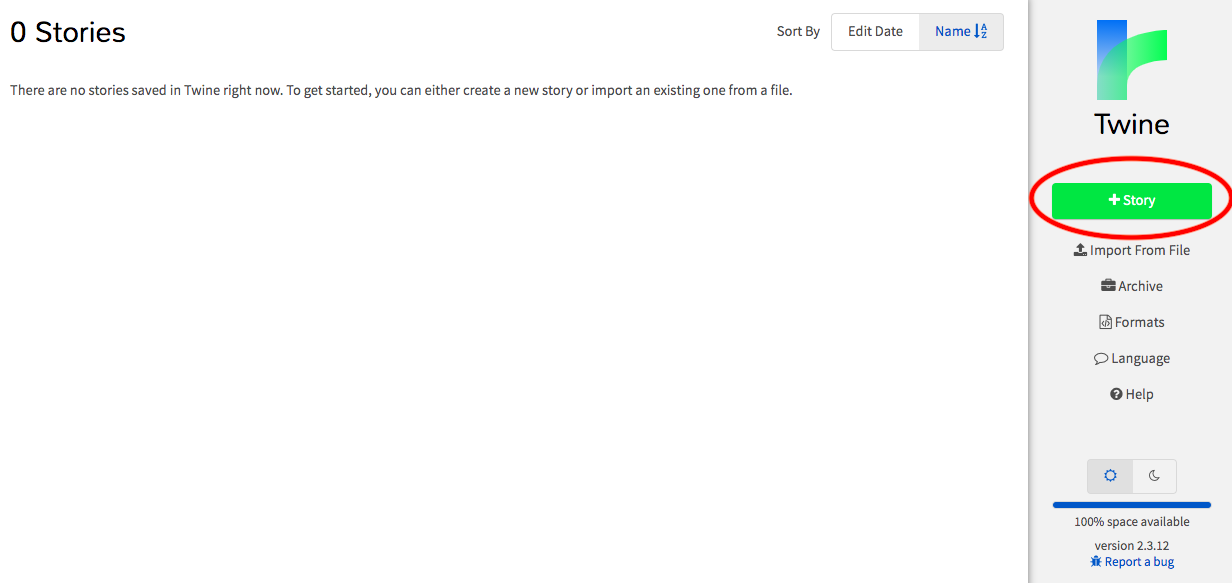

To create your first game, which Twine will refer to as a “story”, go to Twine and click “Use it online.” If it is your first time using Twine, there will be a basic introduction. Once you have read or skipped this introduction, Twine will take you to your story list. At first, this area will be largely empty. It will populate as you create more stories. To create your first story, click “+Story.”

Figure 2. Getting Started with the Browser Version of Twine

Figure 3. Creating Your First Story

You will then be prompted to name your story. I will name my story “First Day in the Office.” Once you type in a name for your story, click “+Add.” Twine will then take you to the story map. This grid is the developer, or creator, view of your story. From here, you can add to and edit your story.

Creating Your First Passage

We are now going to add some content to our game by filling in a passage. The basic organizational unit in Twine is a “passage”. A passage is one “screen” of text that the player will see before navigating to another screen.

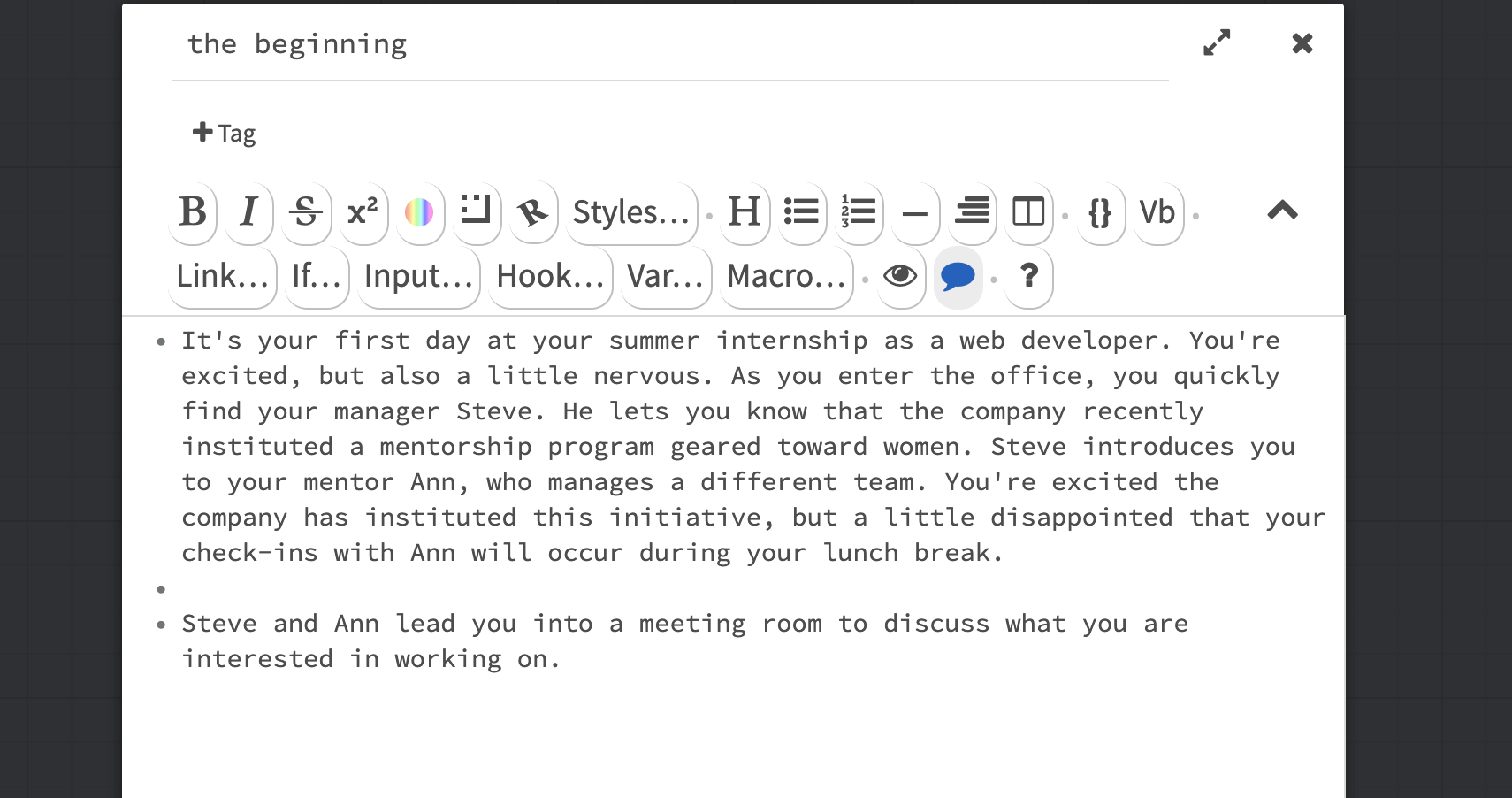

A new Twine story starts out with one blank passage in the middle of the screen. To edit this passage, double click on it. Once you do, the passage will enlarge to reveal a text editing box. For the purposes of this lesson, you can ignore the text-editing menu Twine provides at the top of the passage. Add the title “the beginning”. Add the following text to the body of the passage:

It's your first day at your summer internship as a web developer. You're excited, but also a little nervous. As you enter the office, you quickly find your manager Steve. He lets you know that the company recently instituted a mentorship program geared toward women. Steve introduces you to your mentor Ann, who manages a different team. You're excited the company has instituted this initiative, but a little disappointed that your check-ins with Ann will occur during your lunch break.

Steve and Ann lead you into a meeting room to discuss what you are interested in working on.

Figure 4. Creating Your First Passage

Note that Twine automatically begins each paragraph break (or carriage return) with a bullet. These bullets will not be visible to the player.

To exit the passage, click the “X” in the upper right hand corner of the text editing box, or click anywhere outside of the text editing box. To see what this passage will look like to the player, click the “Play” button at the bottom of the screen. This will open the playable version of the game in another tab in your browser.

Figure 5. Clicking “Play” to Preview Your Story

Figure 6. The Player View of Your First Passage

While many creators choose to immediately plunge players into the fictional world, the first passage presents an opportunity to think about your audience: is your audience familiar with games, or will they need a brief explanation of how to proceed? Do you wish to provide credits and contact information at the beginning or end? Which point of view best fits your rhetorical goals?

Creating Your First Link

At the moment, we have text for the player to read, but no way for the player to interact with the story. Players navigate between different passages using links. To create a link in Twine, place double square brackets around the text that you would like to turn into a link.

If you are still on the tab with the playable version of your story, navigate back to the tab that contains the editing mode of the story. Double click on your passage to edit it, and put double brackets around the words “meeting room” at the end of your passage. Click the “X” in the upper right hand corner of the passage.

Steve and Ann lead you into a [[meeting room]] to discuss what you are interested in working on.

Once you do this, Twine will automatically create a new passage titled “meeting room” that is linked from your first passage. The “meeting room” passage is currently blank. Add the following text to the passage, then click the “Play” button to view the story from the player’s perspective.

Ann smiles encouragingly, and suggests that you might be interested in working with Brad, who is tackling some of the more complex coding challenges on the project.

Steve looks doubtful..."I don't know, Ann, maybe working with the focus group of users would be a better fit?" You hear Ann let out a small sigh. Steve and Ann turn to you expectantly...

Creating Your First Choice

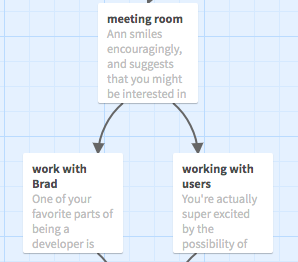

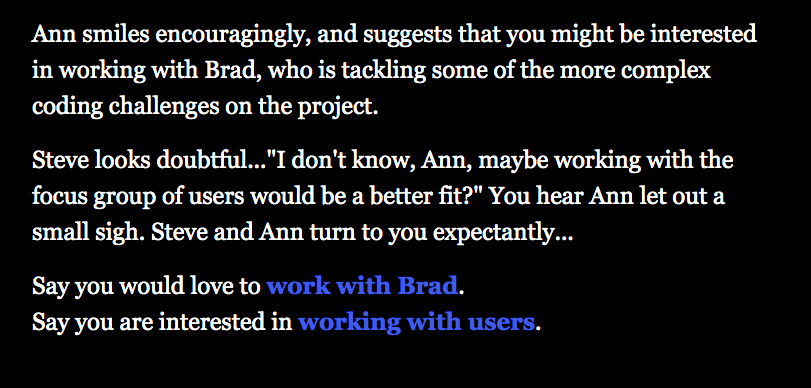

Most text-based games use choices to impact the structure and rhetorical weight of the story. If a single passage contains multiple links, it creates a branching narrative. Try adding a choice to the “meeting room” passage by including two links at the end.

Ann smiles encouragingly, and suggests that you might be interested in working with Brad, who is tackling some of the more complex coding challenges on the project.

Steve looks doubtful..."I don't know, Ann, maybe working with the focus group of users would be a better fit?" You hear Ann let out a small sigh. Steve and Ann turn to you expectantly...

Say you would love to [[work with Brad]].

Say you are interested in [[working with users]].

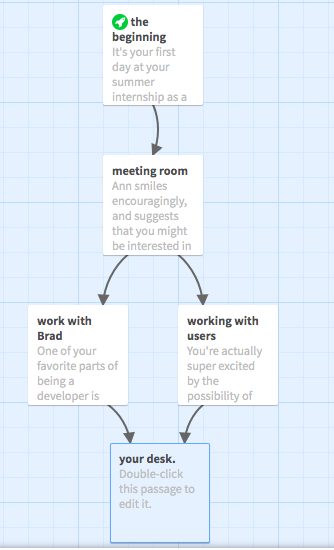

This passage will present the player with two links: “work with Brad” and “working with users”. When you create these links, Twine will automatically create two new passages. The result will be a branching narrative. The first figure below shows the appearance of this narrative in the developer view, the second shows what the game will look like to the player:

Figure 7. Branching Narrative in Twine

Figure 8. How a Branching Narrative Appears in Game

Developing Your Choices

Now that we know how to create a choice, let’s work on creating choices that will matter to the player. Fair choices, meaningful choices, and difficult choices are three important concepts for creating a Twine game.

Fair Choices

A choice is “fair” if the player can understand the relationship between the choice and the outcome. Say that clicking “work with Brad” results in victory, whereas “working with users” results in a loss. If no additional context is given, this choice is unfair because the consequences appear random, and are not logically connected to the player’s choice.

Meaningful Choices

A meaningful choice is a choice that matters. It will likely connect to the game’s outcomes. Say that clicking on “work with Brad” and clicking on “working with users” result in emotionally similar outcomes that do not advance the plot or further character development. This choice is meaningless because it does not carry emotional weight. This is not to say that every choice must produce a radically different outcome. For example, perhaps regardless of what the player chooses, the player character is forced to work with users. We can leverage the ineffectual nature of this “choice” to create a feeling of powerlessness.

Difficult Choices

A choice is difficult if it requires the player to weigh positive and negative risks, possibilities, and costs. In my game, the player character feels pressure from Steve and Ann. Add the following text to the “work with Brad” passage.

One of your favorite parts of being a developer is actually working with users--you've got great communication skills. However, you are well aware of the stereotype that female devs are better at "soft skills" than programming. You're afraid of playing into that stereotype and of letting Ann down. You don't want to make it more difficult for her or any other women at the company by playing into a stereotype. You wish you could make a different choice, but don't know how to explain all of this to two people you barely know. Looks like you'll be working with Brad.

After the meeting, Steve shows you to [[your desk]].

Add the following text to the “working with users” passage.

You're actually super excited by the possibility of working with users--it's one of your favorite parts of what you do. You're confident in your technical abilities, but are hoping to land a job as a liaison between devs and clients after school. While you're initially happy you were honest, you see a frown cross Ann's face and think you see Steve smirk. You're aware of the stereotype that female devs are better at "soft skills" than programming and worry that you just confirmed Steve's bias and made Ann's life more difficult.

After the meeting, Steve shows you to [[your desk]].

The structure of your Twine story should now include five passages.

Figure 9. The Structure of Your 5 Passage Twine Story

The choice between “work with Brad” and “working with users” results in two different outcomes that are logically connected to the decisions the player made. The choices are positioned to impact the player character emotionally, and to shape the development of the story. Neither choice represents a clear “right answer.”

Adding Technical Complexity

Whether or not choices are fair, meaningful, and difficult often depends on writing. However, emotional weight and complexity can also be added by using code to track player choices. If you track a player’s choices, you can change the outcomes, presentation, and styling of the game based on these choices.

Twine supports elements of HTML (the same language used to create webpages) and CSS (the same language used to style webpages). It also supports its own coding syntax, referred to as macros. Macros can be used to create timers, scoring, and text that changes based on the decisions a player makes.

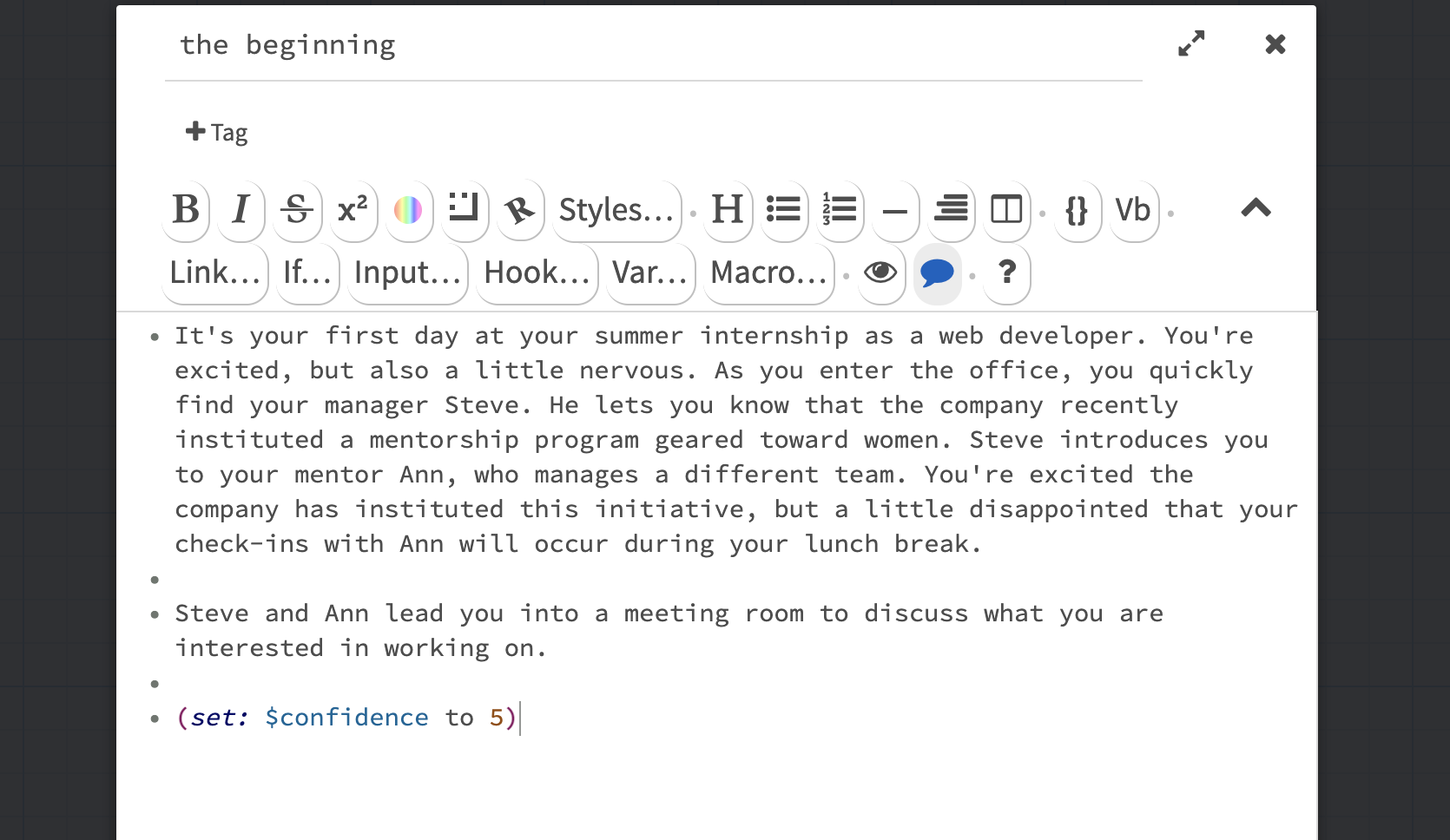

I am going to use macros to keep track of the player’s choices throughout my game. Place the following “set” macro at the bottom of “the beginning” passage.

Steve and Ann lead you into a [[meeting room]] to discuss what you are interested in working on.

(set: $confidence to 5)

Figure 10. Adding the ‘set’ Variable

I am using the “set” macro to create a variable called confidence. You want to create your variables on your very first passage, so that you can keep track of them. The player will not be able to see them. Most macros are nested inside of parenthesis and include a colon after the name of the macro.

I can use the confidence variable to keep track of the player’s choices. Place the following macro at the end of the “work with Brad” passage.

(set: $confidence to it -1)

After choosing that passage, confidence is now equal to four. In and of itself, this doesn’t accomplish anything. The player will not see the confidence variable unless I choose to show it to them. The following line of code (which you do not need to add to the game) will display the value of confidence:

(print: $confidence)

The “print” macro displays the following value to the player. I can also change what happens in the story based on the value of a variable. Place the following text on the final “your desk” passage.

You sit down at your desk and think about your choices.

(if: $confidence is < 5)[You are having serious doubts about whether you are cut out for this. It's not just the technical stuff, it's the ability to work with the team. You start to wonder if you should switch majors...]

(else:)[Today was a lot, but you realize that a lot of the challenges you encountered aren't your fault and you're impressed with your ability to stand up for yourself.]

The first sentence of this passage will display regardless of whether the player chooses “work with Brad” or “working with users.”

However, the following “if” macro allows me to create a conditional statement: if x then y. Above, this macro means that, when the player reaches this passage, “if” the confidence variable is less than five, Twine will display the text contained in single brackets immediately after the “if” macro. The text in single brackets is called a “hook”. A hook is what will happen if the proceeding macro is true.

Students are often excited to use macros and hooks because they increase technical complexity. Programming can be fun! However, it’s important to spend time on why macros can help tell a more compelling story. Add the following macros after setting the confidence variable at the end of “the beginning” passage.

(set: $energy to 5)

(set: $isolation to 0)

You now have three variables: confidence, energy, and isolation. Consider how these variables could interact if the player decides to take manager Steve’s suggestion to work with users, rather than take mentor Ann’s suggest to work with Brad:

You're actually super excited by the possibility of working with users--it's one of your favorite parts of what you do. You're confident in your technical abilities, but are hoping to land a job as a liaison between devs and clients after school. While you're initially happy you were honest, you see a frown cross Ann's face and think you see Steve smirk. You're aware of the stereotype that female devs are better at "soft skills" than programming and worry that you just confirmed Steve's bias and made Ann's life more difficult.

After the meeting, Steve shows you to [[your desk]].

(set: $energy to it -1)

(set: $isolation to it +1)

Deciding to work with users does not negatively impact the player character’s confidence. The player character isn’t insecure about her technical abilities, she would just rather work with users. However, the choice does take an emotional toll and causes the player character to feel isolated from her mentor Ann. Conversely, deciding to work on the complex programming task negatively impacts the player character’s confidence, not because she isn’t capable, but because she isn’t interested.

Let’s work through one more example. Change the choice on the “work with Brad” passage and the “working with users” passages from

After the meeting, Steve shows you to [[your desk]].

to

After the meeting, do you follow Steve to [[your desk]] or [[excuse yourself]] to collect your thoughts?

This will create a new passage titled “excuse yourself”. Add the following text to the “excuse yourself” passage:

You walk down the hall to the breakroom to get some air. You notice a bunch of framed photos on the wall--a collection of "employee of the month" headshots. While the faces all look friendly, you notice that none of them look like you.

Before you know it, it's time to head to [[your desk]].

(set: $isolation to it +1)

The player can now either go directly from “work with Brad” or “working with users” to “your desk” or first take a detour to “excuse yourself”. If they take this detour, it will further raise their isolation.

Now, let’s add an additional “if” statement to the “your desk” passage:

You sit down at your desk and think about your choices.

(if: $confidence is < 5)[You are having serious doubts about whether you are cut out for this. It's not just the technical stuff, it's the ability to work with the team. You start to wonder if you should switch majors...]

(if: $confidence is < 5 and $isolation is > 0)[You are sure that this internship, and perhaps your choice in majors, was a mistake. You feel like you do not fit in and are [[not good enough]] to continue on with the company.]

(else:)[Today was alot, but you realize that a lot of the challenges you encountered aren't your fault and you're impressed with your ability to stand up for yourself.]

You can use multiple “if” statements to create different outcomes. You can also string conditionals together in a single if statement using “and.” Here, we specify a new ending if the player has made choices that result in confidence being less than five and isolation being more than zero. This ensures the player gets a unique ending if they choose a specific path–namely, “work with Brad” followed by “excuse yourself”.

Within this outcome, we have created a link to a new passage titled “not good enough”. It is possible to create new passages using conditionals so that paths in the story open up depending on the choices that players make. Let’s add the following text to the “not good enough” passage to finish our story:

Many women in the tech industry deal with imposter syndrome. This is not simply a result of low-confidence levels; it can be directly caused by biases in the workplace. It is not a simple problem to fix, but there are actions that colleagues and mentors can take to make the environment more welcoming and equitable. What might Steve, Ann, and you, the player, have [[done differently-->the beginning]]?

This passage now links back to the beginning of the game. Using “–>” within a link makes the text on the left visible to the player, while the text on the right is not displayed, but determines the passage of the game the player will travel to.

Throughout our game, choices offer a tradeoff. Speaking up might increase confidence, but result in fatigue. The variables interact to create difficult choices. There is no “right” answer. In addition, the variables counter player expectations. The player might think that “excusing yourself” will help the player character regroup, when, in actuality, it further exposes them to a non-inclusive workplace environment. You can then leverage these choices to present different outcomes at the end of the game.

Styling Your Game

While Twine is a text-based platform, it is possible to incorporate images, sound, and other visual elements into your game. Basic textual styling, like italicizing, bolding, and adding a strikethrough can be accomplished by wrapping text in special characters: double forward slashes are used for italics (//text//), double tildes for strikethroughs (∼∼text∼∼), and double single quotation marks for bold (‘‘text’’). Harlowe 3.2 now also includes a toolbar directly in each passage that will allow you to automatically style selected text.

Macros and hooks can be used to apply slightly more complex styling, such as changes in font color. On your “the beginning” passage, try replacing the sentence “You’re excited, but also a little nervous.” With the following:

You're (color: yellow)[excited], but also a little (text-style: "shudder") [nervous].

The “color” macro with the value “yellow” will turn the word “excited” yellow. The “text-style” macro with the value “shudder” will cause the word nervous to move from side to side.

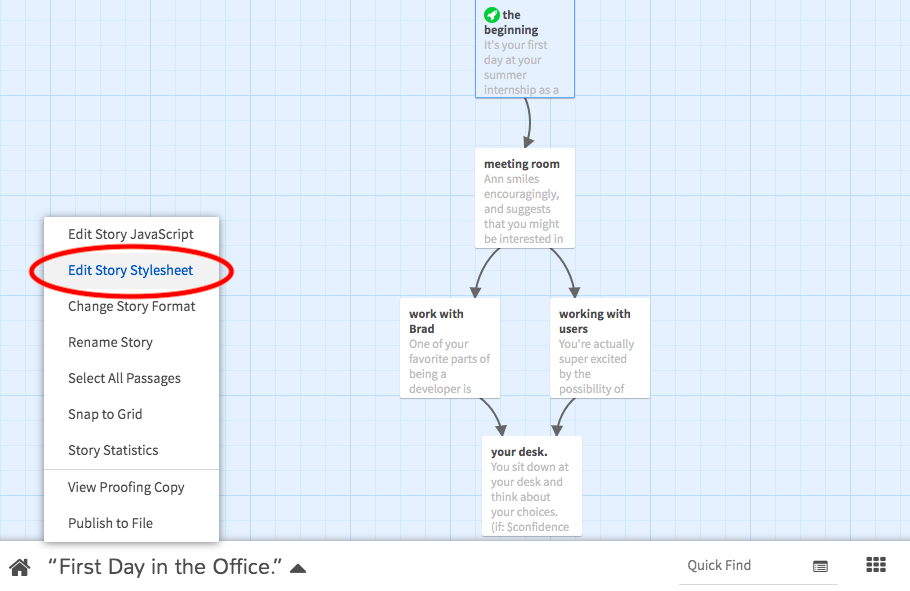

Twine is an HTML based language and can also be styled using an attached CSS stylesheet. You can access the stylesheet (which by default is empty) by clicking the triangle at the bottom left hand corner of your developer screen and then clicking “Edit Story Stylesheet.”

Figure 11. Editing the Story Stylesheet

Try adding the CSS below to your game’s stylesheet. When you are done, click “Play” to see how the changes will show up for the player.

tw-story {background-color: white;

color: grey;}

This CSS changes the background color of the game to white (from the default black) and the font color to grey (from the default white). CSS expressions begin with a selector, the selector indicates which portion of the text you want to style. In this case, the special “tw-story” selector, indicates that the styling will be applied to the entire Twine story. There are some selectors, like “tw-story,” that are unique to Twine.

One common point of confusion is when to use macros for styling and when to use the stylesheet. Typically, it is easier to make changes to individual words or passages using a macro and easier to apply changes to the entire game or to large sections of the game using the stylesheet.

As with macros, it is important to ask your students what purpose styling serves; does it contribute to the game’s argument or the emotions the game is producing? It is tempting to spend time on styling that does not actually contribute to the rhetorical sophistication of the game. The text with a strikethrough from Depression Quest (Figure 1.) is a great example of styling that adds meaning.

Adding Multimedia to Your Game

Twine supports multimedia, including images and sound. It is possible to add an image using the browser-based version of Twine. You can do this by using the HTML tag for inserting an image. Try inserting the following line on any passage in your game. It will display an image of a butterfly:

<img src="https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/43/Morpho_peleides_qtl4.jpg" alt="butterfly" width="500" heigh="600">

If you are using the browser version of Twine, the images you add must be hosted on the web. This means the url should end with an image file extension, such as .jpg. Putting the url for a webpage that contains an image will not work. Wikimedia is a helpful place to find jpgs that you can insert in an HTML img tag.

However, adding images and sound is best accomplished using the desktop version of Twine. There are several helpful tutorials on how to add sound. When working with multimedia on the desktop version, the most common problem students encounter is that image and sound files must be stored in the same folder on the computer as the HTML Twine game file.

Saving Your Game

You have now created your first Twine game! Your game is six passages long, involves three variables, and can result in three endings (based on your use of “if” and “else” macros).

Before playing with and adding to your game, you should take a moment to save your progress. When you are using Twine in the browser, you will want to download a copy of your story at the end of each working session and upload a copy of your game at the beginning of each new session. Twine does not actually save your work in the browser! It only caches your progress. This means that if you run a software update or clear your browsing history, your content will not be saved.

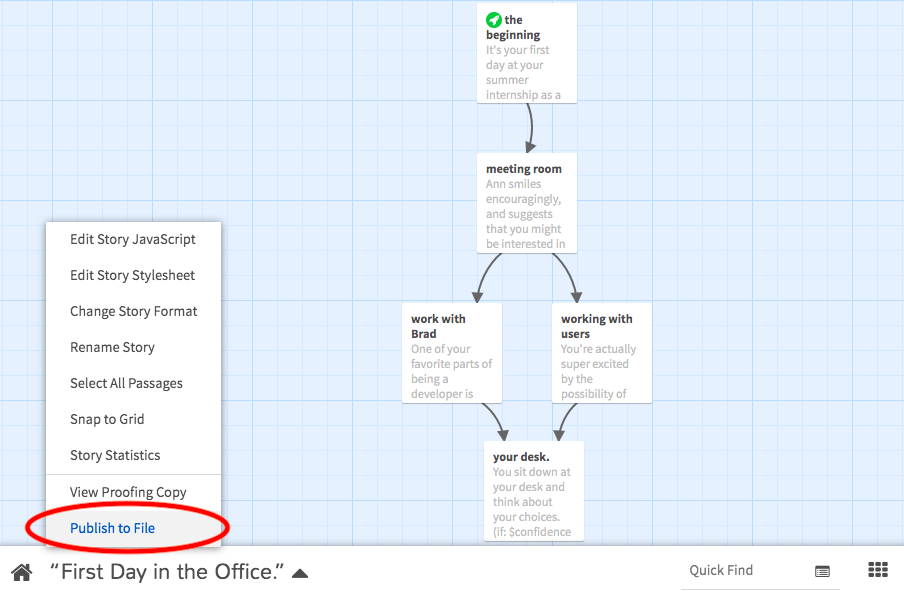

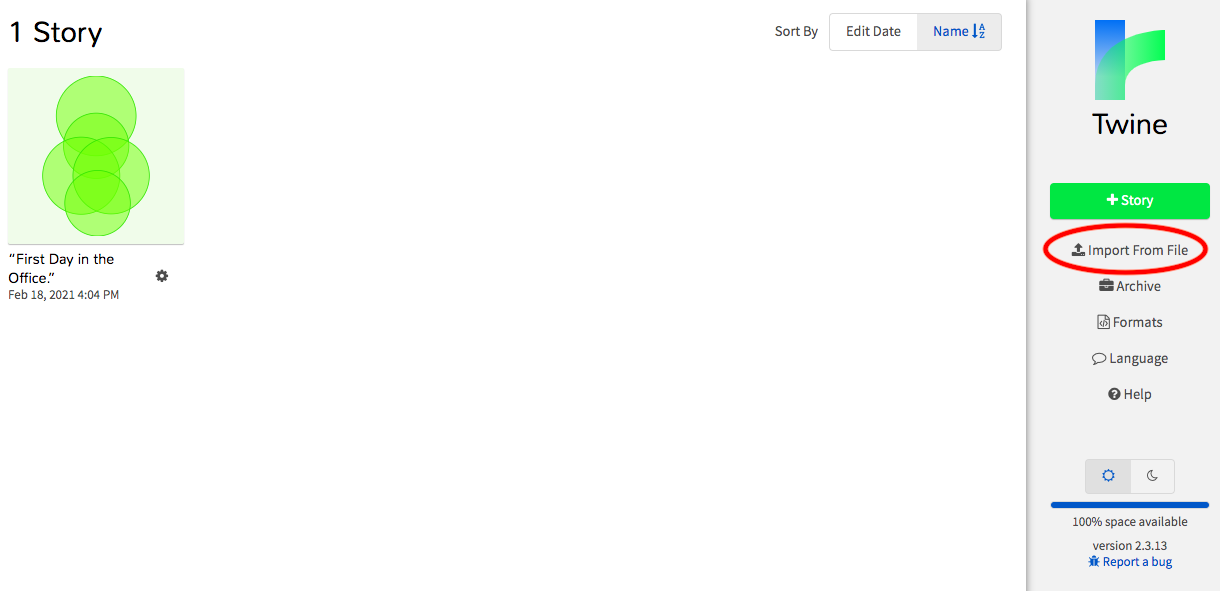

To download your work, click the triangle at the bottom left hand corner of the screen and then click “Publish to File.” This will download an HTML file of your game into your Downloads folder. You can than upload this HTML file by clicking the “Import From File” button under the “+ Story” button.

Figure 12. Publishing Your Game to File

Figure 13. Uploading Your HTML File to Twine

It is possible to share your Twine game by distributing the HTML file. You can do this by emailing it, uploading it to a file hosting platform (like DropBox), or hosting it online. You might consider uploading your Twine game to Github, or to a game hosting platform like itchio.

The fact that Twine games save as HTML files makes it easy to upload and view the “back-end” of games that you find inspirational in the browser version of Twine. This can be a great way to improve your Twine skills.

What’s Next?

Now that you know how to create a Twine game, you might be wondering when and how to integrate Twine into a course. Because of Twine’s accessibility, it is possible to teach game creation as a single small assignment or to organize an entire course around creating games. This is also true of additional game creation tools beyond Twine. You might consider looking into additional tools to find a platform that fits your goals.

Regardless of how you employ game creation and the platform you use, the goal of game creation in the humanities is not purely technical. For example, in the game we created, we employed macros, but only to further the rhetorical goal of the game: illustrating the biases that many women experience in the tech industry. Our use of variables and multiple endings attempt to draw the player’s attention to the ways in which workplace discrimination can forestall “good” or “easy” choices.

The most common pitfalls I experience in teaching games largely stem from focusing on technical, as opposed to rhetorical, considerations. Without careful scaffolding, it is easy for students (and scholars) to:

- Have a difficult time moving past low technical confidence levels

- Create games that enforce harmful power dynamics or cultural stereotypes

- Create games in which design choices do not support rhetorical goals

- Create games that do not adequately consider the intended audience

The first challenge can often be alleviated by stressing the aspects of game design that draw on humanistic, rather than technical skills, such as writing, research, and creativity. Low confidence levels can also be addressed by gradually building up technical skills in Twine. The other challenges can be partially addressed through the scaffolding strategies (playing a game, analyzing a game, providing context) that I discuss earlier. Workshopping (both with the instructor and with peers) is also important for game creation, as the player rarely approaches a game in the way the creator imagined8. Having students watch as their peers play their game, helps them to consider the way their own positionality impacted their design choices.

The course assignment examples below suggest additional strategies for alleviating these challenges. A common thread among these classes is that instructors start by building important humanistic knowledge and skills before moving on to game creation. In a History classroom, this might mean teaching students how to perform historical research, question dominant historical narratives, and critique representations of history before asking them to create a game about a historical figure. In a Women and Gender Studies classroom, this might mean familiarizing students with terminology from feminist and queer theory before asking them to create their own game about gender issues.

Game Assignments

Below are a few examples from myself and others of how game assignments can be integrated into a course.

Highschool History, Ninth-grade Ancient World History

Jeremiah McCall has written extensively about the benefits of teaching Twine in the History classroom. McCall has integrated a long-term (one quarter to one semester long) Twine “interactive history project” into several of his classes. For this assignment, students create a game centered on a historical figure. They must first perform extensive research on the figure and time period before completing a research essay that helps them plan the game. A key component of this essay is that students must answer the questions: What choices (and actions) did the historical figure make and why? What were the consequences of those choices?

College Writing, Composition Classroom

Jonathan Kotchian advocates using interactive fiction platforms (including Twine) to teach composition. Kotchian first has his students play an interactive fiction game. He notes that interactive fiction is especially useful for highlighting reader response—students will each have a different experience playing the game, which helps the class understand the way in which all texts actively construct their audiences. Students then create their own game. Kotchian notes that game creation puts a heightened emphasis on the processes of drafting, collating, and revising.

College English, Intro to Women’s Writing

In this class, I teach women’s literature from 1890 to the present, with an emphasis on historical context and connections to the present. The course moves forward chronologically and the last two-week unit focuses on games. Students read about Gamergate and play games by female creators. For their final assignment, each student creates a Twine game about their opinions on an issue we have discussed in class. Students have chosen to create games on issues such as the intersection of mental health and gender, workplace discrimination, and body shaming.

College English, Intro to Digital Humanities

In this class, I teach a variety of digital methodologies useful to the humanities scholar, including computational text analysis and geographic information systems (GIS). I also ask students to consider cultural issues surrounding technology, such as algorithmic bias. During the last three week unit, students play, analyze, and learn to make Twine games. For their final assignment, each student creates a Twine game that makes an argument about technology. In the past, students have chosen to create games about issues such as social media usage and mental health, online bullying, and gaming addiction.

Resources

If you would like to play with Twine or potentially integrate it into a course, you may want to start by playing some Twine games to get a sense of what is possible. The following is a list of resources pertaining to Twine and interactive fiction in the classroom. All of the games are free and most can be played in under 15 minutes, making them suitable for communal in-class play sessions.

Twine Games

- A Witch’s Word by RainbowStarbird

- Depression Quest by Zoe Quinn

- Play Smarter Not Harder: Developing Your Scholarly Meta by Jason Helms

- Queers in Love at the End of the World by Anna Anthropy

- September 7th, 2020 by Cait S. Kirby

- The Uncle Who Works for Nintendo by Michael Lutz

Twine Resources

Additional Game Pedagogy Resources

- “Interactive Fiction in the Classroom” by Matthew Farber

- Teaching With Twine by Brandee Easter

Endnotes

-

Krijn H.J. Boom, et al. “Teaching through Play: Using Video Games as a Platform to Teach about the Past.” Paper presented at Communicating the Past in the Digital Age, (2020). ↩

-

James Coltrain and Stephen Ramsay, “Can Video Games Be Humanities Scholarship?” in Debates in the Digital Humanities, edited by Matthew K. Gold and Lauren F. Klein. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2019. ↩

-

Urrichio, William, “Simulation, History, and Computer Games” in Handbook of Computer Games Studies, edited by Joost Raessens and Jeffrey Goldstein, 327-338. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005. ↩

-

For further reading on the relationship between emotions and gameplay, see Anable, Aubrey, Playing With Feelings: Video Games and Affect. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2018; and Salter, Anastasia, “Playing at empathy: Representing and experiencing emotional growth through Twine games.” 2016 IEEE International Conference on Serious Games and Applications for Health (SeGAH), (2016): 1-8. ↩

-

For more information about the origins of interactive fiction, see, Aaron A. Reed, “1981: His Majesty’s Ship ‘Impetuous’,” 50 Years of Text Games. ↩

-

For more information about who identifies as a “gamer” and why, see, Adrienne Shaw, “Do You Identify as a Gamer? Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Gamer Identity.” New Media & Society 14, no. 1, (2012): 28-44. ↩

-

Janet Davis, “5 Ways to Welcome Women to Computer Science,” Chronicle of Higher Education (Nov. 18, 2019). ↩

-

For more information about how players often go against the intentions of creators, see, Stephen Granade, “The Player Will Get It Wrong,” Brass Lantern: The Adventure Game Website. ↩